| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

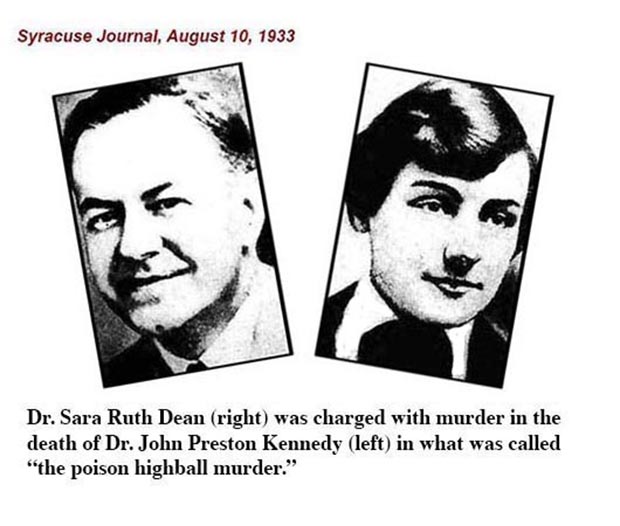

By JACK MAJOR The early 1930s had, I think, more than its share of fascinating murders and resulting trials. That impression may be due to the extensive, often sensationalized coverage certain murders received back when Americans got most of their news from newspapers, and nothing sold newspapers more than juicy murder cases. The so-called woke generation may carp that the murders that mattered to newspapers and their readers had two things in common — the victims were white, and so were the accused murderers. Domestic violence was responsible for most of the murders, but unless they involved celebrities, newspapers generally were interested only if a third party were involved. The public wasn't interested in murders prompted by squabbles over family finances, a husband's drinking, or his unemployment. Everyone had those problems; they wanted something sexy, a murder that revolved around the eternal triangle. By the 1930s, the victims were often men, the accused often women, and while I have no statistics to support this statement, women were usually acquitted by the juries, which almost always were all-male. This was not just my observation — it was widely believed that juries were reluctant to convict women of capital crimes, and when evidence dictated that a guilty verdict was justified, judges were reluctant to impose the death penalty. Some women complained that if the defendant were young and attractive, she might even be acquitted when the evidence proved she were guilty. Well-educated women enjoyed an advantage over women who failed to graduate from high school. Or so it was said. It also was believed poison was a woman's murder weapon of choice, and in 1933, there were two much-publicized cases that yielded opposite results, which, on the surface, wasn't surprising, because many observers believed one woman would be found guilty, the other not guilty, and that's how it worked out — except the woman who appeared to be guilty was acquitted, the woman who shouldn't have been charged in the first place was found guilty. What follows is the story of the second woman, Dr. Sara Ruth Dean of Greenwood, Mississippi. The other woman was Jessie Costello of Salem, Massachusetts, whose story is told elsewhere. Not that Mrs. Costello should have been found guilty; her attorneys made a strong argument in her defense. But in her case, the cause of her husband's death was firmly established. And they lived together in the home where he swallowed the poison, perhaps accidentally, perhaps in deliberately in an act of suicide. But no one ever proved what poison killed Dr. John Preston Kennedy, or how it came to be in his body. He and Dr. Dean were lovers; their affair broke up his marriage. But she said their affair was over, and she was engaged to someone else. Further, she said she wasn't with Dr. Kennedy on the night of July 27, 1933, when he became fatally ill. The state couldn't prove she was lying. Further, for the first six days of his ten-day illness, Dr. Kennedy claimed the cause was ptomaine poisoning from a pork sandwich. However, Dr. Kennedy's two brothers, Doctors Henry and Barney Kennedy, claimed that on the sixth night, while Dr. Preston Kennedy was lying in a hospital bed, he told them he had been poisoned by Dr. Dean. Oddly, when he died, four days later, his brothers did not ask for an autopsy. They had their brother's body embalmed and buried the next day, which complicated matters when the district attorney decided to charge Dr. Dean with murder. |

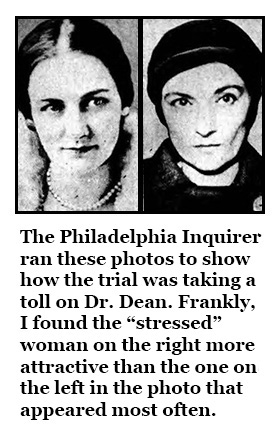

Setting the stage Throughout the country, of course, there were many other women doctors. Strangely, one of the oldest, 62-year-old Dr. Alice Lindsay Wynekoop of Chicago, would go on trial for murder at the same time Dr. Dean was being tried in Mississippi. Dr. Wynekoop's victim was her daughter-in-law; her weapon was a gun. Because Dr. Dean was ahead of her time, she was misunderstood. My guess is the photo of her at the top of the page was taken while she was at the University of Virginia. She had an attractive face, but might have been mistaken for a young man. As a high school student in Greenwood, she had no dates, no social life, and reportedly that didn't change when she went to college. She picked up a reputation as a man-hater and an atheist. She was neither, but reputations are hard to shake. Jessie Costello, the Massachusetts housewife mentioned earlier, was acquitted weeks before Dr. Dean was even charged with murder. In her trial, Mrs. Costello charmed the all-male jury. Four of the jurors formed a barbershop quartet and, during breaks, sang. One of their songs: My Wild Irish Rose. Though you can't prove it with photos, Mrs. Costello was considered lovely and vivacious, a bit of a flirt who became known during her trial as "The Smiling Widow." Dr. Ruth Dean seldom smiled. She seldom showed any emotion until, weeks into her trial, the stress became too much, but her meltdown was brief. She was a woman very much in control. However, the woman who wrote the letters that were introduced during the trial was quite different. She may have been an excellent, no-nonsense doctor, but she also appears to have been a hopeless romantic. The contrast between her professional and personal behavior was as striking as the difference between Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. To the prosecution, however, she was a home wrecker who killed Dr. Kennedy after he told her he was going back to the woman who divorced him four months earlier. Dr. John Preston Kennedy was 41-years-old when he died. A native of a tiny village near Jackson, Mississippi, about 100 miles south of Greenwood, he seemed to have become a successful surgeon in the city of about 12,000 residents. In 1928, he moved into the Physicians and Surgeons Building that he had commissioned. His brother, Dr. Henry Kennedy, was a dentist, who had an office nearby, and his other brother, Dr. Barney Kennedy, also practiced in Greenwood, though he got short shrift in the trial coverage, with brother Henry grabbing most of the attention. After Dr. Dean graduated from the University of Virginia and returned home to Greenwood, Dr. Preston Kennedy was among the first to welcome her, and she became one of the first doctors to move into his new building. Their affair began shortly thereafter, much to the chagrin of brother Henry, who soon faced questions from Preston's wife, Bessie, who had suspicions about her husband and Dr. Dean. Henry Kennedy and his wife apparently were Bessie Kennedy's closest friends, and briefly took her into their home after she walked out on her cheating husband. Preston and Bessie Kennedy reconciled and separated several times before she divorced him in 1933 |

Let the show begin Meanwhile, the surviving Kennedy brothers went about repairing the image of their dead brother, who had cheated on his wife with at least one woman. Within a week of his death, Preston Kennedy was hailed as a hero, thanks to stories such as the one that follows: |

|

|

| When details of that operation became known, the reputation of Dr. Kennedy should have been ruined, but apparently it wasn't. The prosecution would ignore or deny several unsavory aspects of the man's character and his lifestyle, blame the break-up of his marriage entirely on Dr. Dean. One reason the trial might have gone the way that it did was the order in which these proceedings go — prosecution first, then the defense. In this case, the trial ran longer than expected, and the sequestered jury, which included seven cotton planters, became restless early on. By the time the team of defense attorneys destroyed the state's flimsy case, most jurors had made up their minds. This trial would be better recalled today as a gross miscarriage of justice if it weren't for the Mississippi governor who months later made a Solomon-like decision. |

This really was fake news How many people in Greenwood actually saw Asbury's first piece a week before the trial began, I don't know, but if Dr. Ruth Dean really were a murderer, Asbury would have been her second victim. His first paragraph: "The trial of Dr. Dean is expected to reveal the pitiful philosophy and queer psychology of the man-hating type of woman, who, after years of suppressing normal instincts and desires, usually climaxes and violently disrupts her life by sweeping aside every inhibition in one terrific emotional explosion ... Dr. Dean, a tall, handsome brunette with big blue eyes and a soft mobile mouth, is typical of the so-called American bachelor girl. She has always been solitary, both by habit and inclination ... Whenever possible, she shunned the parties, socials, candy-pullings and other gay gatherings which to most young women are almost as important as the very breath of life." And in his last paragraph, Asbury was dead wrong: "So far as anyone in Greenwood was aware, she and Dr. Kennedy carried on no love affair, though developments immediately before and after Dr. Kennedy's death indicate there may have been much between them of which they alone knew." Anyone in Greenwood who didn't know about the affair simply wasn't paying attention. Mrs. Kennedy discovered the affair in 1931, and Dr. Dean left Greenwood soon afterward to take a position at Beebe Hospital in Lewes, Delaware. She and Dr. Kennedy continued to write to each other, the met at least once, in Baltimore, and after a divorce was certain, Dr. Dean returned to Greenwood at the end of 1932. Before that, Dr. Kennedy wrote to Dr. Dean, "These damn gossiping women's tongues are loose at both ends." A few days later, in another letter, Dr. Kennedy said, "These women's tongues are going full blast again since the separation became known." The whole town must have known what was behind Bessie Kennedy's grounds for divorce — cruel and inhuman treatment. Her husband's affair with Dr. Dean was well known. He'd even talked about leaving Greenwood and joining her in Delaware. As for Asbury, I found only three more trial articles with his byline. Most trial stories in Hearst-owned newspapers carried a different byline. |

| Black spectators soon excluded Day one of the trial. Picture the courtroom in "To Kill a Mockingbird," with white citizens on the first floor, blacks seated in a balcony overlooking the proceedings. The crowd was estimated about about 500, but this was for the jury selection. When things became more interesting, the courtroom was packed. One journalist estimated 1,000 people were jammed inside, but interested blacks were squeezed out, because judge, S. F. Davis, ruled that white spectators had first dibs on all seats. He then announced blacks weren't allowed under any circumstances, though there were two days blacks should have been in the courtroom. Judge Davis was a colorful figure. Journalist Grace Robinson, whose trial stories appeared in several newspapers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer, said in the January 30, 1934, edition, "Judge Davis has no such prejudice against smoking in a court of law as exists in Northern trial chambers. Indeed, he smokes a large part of the day himself, puffing at his crooked pipe, which he frequently replenished from his brown tobacco pouch while the procession of talesmen came and went. "Once proceedings were halted temporarily while he left the courtroom, muttering something about a pain in his stomach. Frequently he descended from the bench to quench an ubiquitous thirst at the water cooler. Once, remarking that he wanted a 'drink', he smiled coyly at the defendant, who is accused of having slipped a dash of mercury into a 'last highball' she handed her lover, Dr. Kennedy." In the February 3 edition, Ms. Robinson wrote, "Judge Davis, pulling on his crooked pipe, has been the personification of easy-going good nature during the tedious trial preliminaries in this little town on the muddy Yazoo River. The first venire of 166 citizens was nearly exhausted before he showed even a trace of irritation" The journalist said the white-haired judge regaled spectators during long lawyers' conference in the corridor outside, and even Dr. Dean, the defendant, laughed heartily at his jokes." Ms. Robinson added, "Judge Davis, although elderly, exhibits the proverbial Southerner's interest in feminine pulchritude. Before the trial, the defense attempted to subpoena hospital witnesses in a preliminary hearing dealing with Dr. Kennedy's supposed death-bed accusation of his attractive medical associate. Judge Davis refused to issue subpoenas. Today one of the witnesses, on a state subpoena for the trial proper, walked into the courtroom and proved to be a stunning blonde. " 'Gosh,' said the judge to reporters sitting near the bend, 'if I'd known she was that good-lookin', I' have subpoenaed her long ago'." Judge Davis often kept the trial in session into the evening in hopes jurors, about half of them cotton planters, wouldn't miss too many days of work, but the judge had his own priorities. The local newspaper, The Greenwood Commonwealth, reported on March 3, 1934, "The judge canceled last night's session in order to attend the Ole Miss - Mississippi State boxing matches," and later reported, "Judge Davis said, 'We'll go on through tonight. They're putting on a show over at the high school tonight with 50 or 60 pretty girls in it and I sure hate to miss it, but I guess I'll have to'." There was a stir on February 11 when Bertie Leflore, a 12-year-old black boy testified for the state, upsetting defense attorneys, who would play the race card by saying no black should have been allowed to testify against a white woman, though it was a desperate ploy by the side that knew it was losing. If analyzed, Leflore's testimony could be seen as damaging the state's case, which was one reason the defense should have given the boy a pass. The other reason was that, by objecting, the defense was admitting something it had previously denied. More on that later. On February 16, without any blacks among the spectators, Judge Davis quickly dispensed with another case before the Dr. Dean trial resumed, The judge sentenced a black man to hang for stealing $1.85 while carrying a firearm. O. C. Brown, 25, became the first in line to be executed under a 1932 Mississippi law providing death for robbery with firearms. Brown claimed he took the money, along with peanut candy, hair oil and smoking tobacco as compensation for money the peddler owed him from a previous transaction. Unfortunately, he did it with a rifle in his hands. (There is no record Brown was ever executed.) Oddly, Brown shot a deputy sheriff in the knee while making his escape from the store, but was not tried for that crime, which under Mississippi law, was a lesser offense. |

Slow start sets the pace The most anticipated days of the trial were those in which the many love letters exchanged by Doctors Dean and Kennedy would be introduced and read aloud, but a whole day was spent having the handwriting on every letter verified by either Dr. Dean or a member of the Kennedy family. The love birds wrote love notes the way people today exchange emails. The state hoped the letters would prove Dr. Dean was the driving force behind the affair, the defense wanted to prove just the opposite. The defense presented the stronger case, but this apparently didn't impress a jury increasingly anxious to return to their homes. However, on the day some of Dr. Dean's letters were read, the jury was momentarily removed from the courtroom to spare them from hearing a legal wrangle. The jury was taken to the room where they'd eventually discuss the case, but on this occasion — shades of the Jessie Costello trial — they spoofed the defendant by singing Let Me Call You Sweetheart. Or so the Associated Press reported on February 15, 1934. |

Jury moved by prosecution witnesses Thalheimer told the court he'd been out of the house on July 27, 1933, until 10 p.m. When he returned, Dr. Kennedy was asleep, but awakened a few minutes later by a telephone call, not unusual, because the doctor often was called away at odd hours. Thalheimer said Kennedy was slow to respond, and by the time he reached the phone, the caller had hung up. Thalheimer said the phone rang again about five minutes later, and this time doctor answered it. Thalheimer said Dr. Kennedy then went to the bathroom, apparently to get ready to leave the house. Certain assumptions were made by Thalheimer that became part of the story that would be endorsed in the jury's verdict. The witness estimated it was 40 minutes between this second phone call and when Dr. Kennedy left the house. Thalheimer said Kennedy never took that long to respond to a medical call, so he concluded it was personal. Thalheimer said the phone rang three more times before he heard Dr. Kennedy leave the house. He did not see Kennedy after the doctor left the porch to answer the phone the second time, so he did not know who had called, or why. Without any supporting evidence, the state would claim Dr. Dean had called Dr. Kennedy four times that evening, demanding to see him for one, final drink together, because she was preparing to leave the state to marry a man she had met while she worked at Beebe Hospital in Lewes, Delaware. That's what she claimed, but at this point in the trial it was easy for the state to say she was not engaged, and what she really meant by a "final drink together" was she intended to make sure that was the last drink Dr. Kennedy ever had. Her motive, claimed the prosecution, was jealousy, because Dr. Kennedy had announced he was going to re-marry his ex-wife. Dr. Dean's alleged weapon was the reason this became known as "The Poison Highball Case" (aka "The Poison Cocktail Trial"). The defense — and Dr. Dean, in particular — did not believe there was any reconciliation in the works for the Kennedys, divorced for only four months. Mrs. Kennedy and the couple's four-year-old daughter were in the Panama Canal Zone when Dr. Kennedy became ill, and when she returned, hours after his death, she brought with her no letters to prove he had been in touch with her in Panama about a reconciliation before he became ill. |

Bad whiskey or tainted pork? Unable to help his porchmate, Thalheimer said Kennedy asked him to call a doctor. He did, and when Dr. George Baskerville arrived, Dr. Kennedy claimed he had ptomaine poisoning from a pork sandwich and whiskey. It would never be established whether, where or when he might have had this sandwich and whiskey. Reading the testimony, as it appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer (February 4, 1934), had its amusing moments. Asked if Dr. Kennedy vomited much, Thalheimer answered, "Yes, every three or four minutes. Finally, I went down to breakfast." As if all that vomiting made the man hungry. Thalheimer's mother-in-law, Mrs. Weiler, 64, testified on what she observed of Dr. Kennedy during the five days he remained in her house until he was taken to the hospital in Jackson. Mrs. Weiler echoed much of what her son-in-law had said, claiming Dr. Kennedy continued to vomit every five minutes, frequently muttering, "I'm literally burning up!" Dr. Kennedy's drinking and drug-taking would become an important issue with the defense. These first two witnesses might not have known about Dr. Kennedy's frequent dependence on morphine, which would be hinted as the real reason the physician went to his office that evening. But Thalheimer and Mrs. Weiler were asked about Dr. Kennedy's drinking. Thalheimer insisted his sleep-porch partner was not a drinking man, and Mrs. Weiler claimed she'd never seen Dr. Kennedy under the influence of liquor, though she did admit he'd often been a guest at her home and had seen him take no more than two small drinks on those occasions. So it was reported in The Greenwood Commonwealth on February 6. |

Truth or an award-winning performance? Judge Davis ruled Dr. Henry Kennedy would testify without the jury present, then he'd decide on the admissibility. After an all-day session, during which the witness and spectators often wept, the judge said jury could hear the testimony the next day. I don't think there's much doubt it was Dr. Henry Kennedy's testimony that decided the case, though it was all hearsay and self-serving, and reasonable doubt seemed obvious during cross examination. Questioned by special prosecutor Fred Witty, Henry Kennedy testified that when he and brother Barney arrived at Baptist Hospital, Preston Kennedy suddenly changed his story. Instead of blaming his illness on a pork sandwich, "Preston said, 'Dr. Ruth Dean gave me a drink of whiskey with poison. I believe there was mercury in it.'" Henry Kennedy said it was his brother, Barney, who asked for more details, and quoted his dying brother's reply: " 'Dr. Dean had been worrying me for some time, especially calling me at night. On this particular night she called several times. I told her I was tired, that I'd been working hard, and didn't want to go out. The last time she called, she said she wasn't going to leave town until I came out. I got up and dressed and went on out there. I got in my car and we came back to my office.' Barney said, 'You mean your office in the Medical Building?' " I found the wording of this account rather strange. Did Barney Kennedy really ask his dying brother to be more specific about the location of this alleged meeting? How many offices did Preston Kennedy have? Henry Kennedy obviously phrased his testimony in anticipation of questions from the prosecutor. I mean, did a man who professed his love for Ruth Dean in more than 100 letters really say "Dr. Ruth Dean gave me a drink of whiskey with poison"? Wouldn't he simply have said, "Ruth gave me a drink ...?" In his continuing effort to qualify his brother for sainthood, Henry Kennedy claimed the dying man did not want to punish Dr. Dean. According to the witness, Preston Kennedy especially pleaded for them not to harm Dr. Dean, or do anything that would keep the Kennedy brothers from meeting some day in heaven. Grace Robinson, in her story about this testimony (The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 6, 1934) wrote, "The statuesque woman defendant, who is said to have renounced her Southern Methodism for atheism, acquired during scientific studies, permitted her lip to curl in a slight smile at the mention of heaven." Shame on Ms. Robinson for writing Dr. Dean "is said to have renounced her Southern Methodism for atheism." Before the trial began, word was leaked that the state intended to make an issue of Dr. Dean's alleged atheism, but that wasn't necessary. The issue was made by Ms. Robinson, Victor Asbury, and other journalists. I suggest Dr. Dean's slight smile was not because she didn't believe in heaven, but because she felt the Kennedy brothers were more likely to meet in hell. |

Let's get it straight Mrs. Boyles and her son, Noy, both testified Dr. Dean never left the house that evening, nor did either of them see Dr. Kennedy. Dr. Dean did admit seeing Dr. Kennedy two nights earlier, and he seemed very upset and had a lot to drink. Dr. Dean's contention was Dr. Kennedy was the jealous one, and had threatened to kill her and himself if she didn't cancel plans to marry Franklin C. Maull, the Lewes, Delaware, river boat captain. Dr. Dean's insistence she really was engaged would come back to hurt her case, but this was another instance of people taking a man's word over hers. More on that later. Henry Kennedy claimed Preston said he and Dr. Dean had several drinks in the wee hours of July 28 before he told her he was tired and wanted to go. Quoting his brother, Henry Kennedy testified, " 'She said, 'Well, let's have a farewell drink before we go. Let's have some water.' Then he said he went out and got some ice water, and when he returned, the drinks were poured. They had a drink, and at once he noticed a strong metallic taste. He said he hurriedly drove Dr. Dean back home, and then turned down Avenue I and stopped by a corner near a little tree." There, Henry Kennedy added, his brother forced himself to vomit, then returned to the office where "he took everything he knew to take to get rid of poison." Again, I couldn't help but notice what seemed an unnecessary detail that I doubted a dying man would include in his statement — that he stopped by a corner near a little tree. What was never explained to anyone's satisfaction is why, as soon as Preston Kennedy returned to the Weiler home, and for almost six days afterward, the man insisted he had ptomaine poisoning, and refused to go to a hospital until the fifth night. |

Much ado about nothing In her February 7 story, Grace Robinson wrote: "He (Henry Kennedy) said he found the note of July 27 still sealed lying on Preston's desk after his death." The state would make much of this note, calling it "the summons letter", though it was never read by the intended recipient. It would be the subject of a blatant lie that, as far as know, went unchallenged when another prosecution witness testified. The state would use this letter to support its contention Dr. Dean was eager to see Dr. Kennedy one last time before she left Mississippi, but the state was confused about her scheduled date of departure, and Dr. Dean's final note was misleading on that very important detail. "My dear," she wrote under the date of July 27, "I missed you last night. Please call me when you get this. Am planning to leave Sunday, and I want to turn over something to you. Best wishes and love — Ruth." Prosecutors would say Dr. Kennedy's indifference kept him from reading the note, though they seemed to assume a note mailed about noon would be delivered within a few hours. That note was addressed to Dr. Kennedy's office, and there was no evidence he ever saw the envelope. Perhaps Dr. Kennedy's nurse or receptionist put the note on his desk the next day, when he failed to come to the office because he was ill. Prosecutors said Dr. Dean, receiving no reply the same day, repeatedly telephoned him that evening. Anyone who worked for Dr. Kennedy must have been familiar with Dr. Dean's handwriting and the frequency of letters exchanged by the two lovers. I imagine there was a lot of eye-rolling by the staffs and patients of both doctors. My point: I can't think of any reason Dr. Dean would be anxious about failure to get a reply. And the Sunday she planned to leave was not July 30, but August 6, something she didn't make clear in the note. According to prosecutors, the "something" Dr. Dean wanted to turn over to Dr. Kennedy was a poisoned cocktail, but when she took the stand, she explained, "Those things were case histories. They were among the things I wished to turn over to him. I had persuaded Dr. Kennedy to apply for membership in the American College of Surgeons. That required he submit a lot of case histories — histories of operations he'd performed. I had assisted him in many operations and I was copying these histories for him. I had about 23 or 24 to give him." Those histories were then offered in court. But timing is everything. The prosecution made its point three weeks earlier, before the jury was noticeably restless. |

| Like a pair of lovestruck teenagers Obviously, Dr. Dean was no angel, but I think she was telling the truth when she admitted she and Dr. Kennedy were together on Tuesday, July 25, and that he had whiskey that evening. Who knows what games they were playing with each other, despite what each was saying about intentions to marry other people. When their love letters were finally made public during the trial, both came off looking like lovestruck teenagers. With Dr. Dean, her adolescent approach to romance might have been caused by her lack of experience with men; with Dr. Kennedy, something else may have been driving him — that male tendency to want his cake and eat it, too. Where the defense scored points — too late, it turned out — was raising doubt about the Kennedy family's story a reconciliation was in the works between Dr. Preston Kennedy and his ex-wife. In the doctor's last few letters to Dr. Dean, he says he is hers for the asking. On the other hand, the ex Mrs. Kennedy was in Panama, and, upon her return, could produce no letters from the man she said she was about to re-marry. ("I tore them up," she would testify.) Dr. Dean said she was making plans to leave Greenwood on August 6 to take a train to Washington, D. C., arriving on August 8, when, she claimed, she would marry Franklin C. Maull, a tug boat captain she'd met while she worked in Lewes, Delaware. Maull was a few years younger than Dr. Dean, and came from a prominent Lewes family, was also a pilot with his own plane. But Maull would turn out to be the chief villain in this story, a poor choice for Dr. Dean to make as an alternative to Dr. Kennedy, whose life had become such a shambles that it's hard to believe any woman would willingly marry him, least of all the woman who'd divorced him earlier in the year. Reading about this case today, it's easier to believe he either committed suicide or accidentally took another morphine overdose, than to think someone murdered him. Defense lawyers would argue Dr. Kennedy was in no shape to make the death-bed statement recited by Dr. Henry Kennedy. What I didn't see mentioned was the possibility Preston Kennedy, in a feverish state, told his brothers about his July 25 meeting with Dr. Dean, and claimed it happened two nights later. The reasonable doubt in this case was overwhelming. Or it should have been. |

Even his hindsight wasn't 20/20 Older, but not wiser, because Dr. Baskerville testified he knew immediately Dr. Kennedy had been poisoned, but yielded to the sick man's diagnosis, food poisoning, while also treating Dr. Kennedy for alcoholic poisoning, and backing off when his patient refused to go to Greenwood Hospital for a reason, that, in light of his medical history, seemed ridiculous. "He didn't want his patients to know he was sick," said Dr. Baskerville. He did not say what excuse was given out to patients who were due to see Dr. Kennedy for the next several days. On Monday, more than three full days after he became ill, Dr. Kennedy was called upon to perform an appendectomy. "I didn't think he was physically able to go through with it," Baskerville testified. But did Dr. Baskerville prevent the obviously weaker man from performing the operation? No. Dr. Baskerville testified Dr. Kennedy "wanted me to give him a hypodermic." He said he refused, but admits that just before Dr. Kennedy started the operation, he noticed Kennedy's eyes were contracted. "I knew," said Dr. Baskerville, "he had given himself the hypodermic before he left home." Great. A sick man, under the influence of morphine, was about to cut a man open, and Dr. Baskerville still didn't stop the operation. Baskerville said at one point Dr. Kennedy's hands "were moving in the wrong direction." Dr. Baskerville described the operation as "an easy case of appendicitis, but I was forced to stand by and guide Preston's hand as he wielded the knife. He was very nervous and told me he felt awfully weak. Finally, he had to give up and I finished the operation alone." The obvious question: Why didn't Dr. Baskerville force Dr. Kennedy to remain at home and perform the "easy" operation himself? Dr. Kennedy collapsed without finishing the operation, and was taken back to the Weiler home. Finally, the next evening, Dr. Kennedy agreed to be taken to Baptist Hospital in Jackson, where, according to his brothers, he changed his story about the cause of his condition. Where the defense felt Dr. Baskerville was lying was a statement he had never seen Dr. Kennedy drunk. Weird that witnesses for the state considered drinking such a taboo, when, under cross-examination, they admitted the man's frequent recreational use of morphine. (Even Dr. Dean, in a 1931 letters to Dr. Kennedy, suggested he'd feel better if he had "a tonic", and she wasn't referring to a drink. "Seriously, why not take one?," she wrote."Get George to give you one." (I realize you cannot fully trust information from what jokingly has been called Dr. Internet, but according to what I found online, the effects of a morphine overdose were much the same as what Dr. Kennedy went through just before he died, and what he'd endured the year before when he admitted that was the cause.) Last point on Dr. Baskerville's testimony: He claimed Dr. Kennedy showed him the so-called "summons letter" and that Kennedy asked his advice. That was a good trick, because if we can believe Dr. Henry Kennedy's testimony, the letter remained sealed in Preston Kennedy's office until after he was dead. Unless, of course, Dr. Baskerville believed Dr. Kennedy was a regular Carnac the Magnificent and could read the note without opening the envelope. Dr. Baskerville wouldn't reveal the advice he gave Dr. Kennedy, but the way the local medical witnesses took sides in this case, it was obvious Baskerville, like Dr. Kennedy's brothers, did not approve of the man's affair with Dr. Dean and thought he should have ended it long before. What one wonders is what kind of advice would he have wanted on July 27? Did he tell Dr. Baskerville he'd planned to re-marry his ex-wife? Or was that a story created by the surviving Kennedy brothers after Preston passed away? |

| Confusion, carelessness or conspiracy? Oddest thing in this very odd case is the two brothers who testified their brothers said he'd been poisoned had Preston Kennedy's body embalmed and buried the day after his death. The body had to be exhumed in order for an incomplete autopsy that failed to reveal a cause of death. Even the state's chief witness on this point said that a trace of mercury poisoning found was not enough to affect Dr. Kennedy in any way. Not mentioned was the poisoning found was something that could have come from eating seafood. Before the trial ended, there was conflicting testimony from "experts" on both sides about the cause of Dr. Kennedy's death, but no one could deny that a year prior to his death he was similarly ill, and the cause was an overdose of morphine, which was the man's drug of choice, though defense witnesses said Kennedy also was a heavy drinker. One state's witness, Mrs. Albert Weiler, said Dr. Kennedy frequently complained, "I'm literally burning up!" Defense witness, Dr. J. P. Bates of Greenwood, said a person suffering from mercurial poisoning has a temperature ranging from normal to subnormal until within 12 hours of death. The hospital chart showed Dr. Kennedy's temperature was above normal. Another defense witness, Dr. L. B. Otken, also of Greenwood, said what passed for an autopsy of Dr. Kennedy was useless. He also said a fatal dose of mercury poisoning would have killed Dr. Kennedy much faster than ten days, and he never would have been able to attempt an appendicitis operation on the fourth day. State witness Dr. W. F. Hand, who performed the postmortem examination of the body, said minute traces of mercury were found, but another witness said no evidence of mercury was found. |

| 'Beautiful' versus 'brilliant' I interrupt this story for some words about appearances and labels. Journalists can't resist using them when they write about people, and why not? Inquiring minds want to know.

The most used photograph of Dr. Dean (the one with the pearls, right) made her appear older than her listed age — 33, though there would be a good reason for that, as she admitted under oath. There are photos in which she looks younger and more attractive, and photos that make her look older and homely. You just can't tell. Likewise, photos of Dr. Kennedy's ex-wife make her look older than her 33 years, and very much like the prototypical school teacher from the 1930s. But you'd never know that from the descriptions that appeared in newspapers that covered the trial. This was particularly true in the Grace Robinson story that previewed Mrs. Kennedy's testimony: |

|

|

I'm sure neither woman was pleased by that "more beautiful, but less gifted" line. Mrs. Kennedy was a college graduate who taught school for awhile, and was sharp enough, with help from a shrewd lawyer, to win an incredibly favorable divorce settlement in March, 1933. As Grace Robinson explained in The Philadelphia Inquirer (February 9, 1934): "Dr. Kennedy relinquished custody of his small daughter, Annie Margaret, to his wife, with permission to visit the child "at reasonable times." He was required to pay his ex-wife $160 a month, payable in advance beginning with April, "until the complainant remarries." The court remarked the sum had been fixed with consideration of the business depression, and suggested the amount might be raised when times got better. "Dr. Kennedy was required to keep up a $5,000 educational policy with the New York Life Insurance Company, and also his government insurance of $10,000, both made over to his daughter. "He was required to keep up his $25,000 regular life insurance, payable to his wife, and was enjoined from changing his beneficiaries at any future time. He also was forced to pay their medical and doctor bills, to furnish his wife with funds to take her master's degree at college, and buy her a new automobile within 60 days after the date of the decree." |

As the World Turns Under the generous terms of the divorce, and the shaky state of Dr. Kennedy's finances in mid-1933, it was difficult to believe Mrs. Kennedy had agreed to a reconciliation. She admitted during cross-examination her testimony was motivated by revenge on Dr. Dean. She also said she'd made plans to start suit to collect double indemnities, payable if it were proven Kennedy died "by external violence." She and her daughter would receive $97,000 if her suit succeeded. Shortly before his death, a check that Dr. Kennedy wrote for six dollars bounced. On the day he died, he had $80 in the bank. The problem was the Depression. Patients owed him $16,238, of which, according to Dr. Henry Kennedy, his brother had succeeded in collecting only $602. For the most part, Mrs. Kennedy seemed to be testifying at a divorce trial. She told how she played detective in 1931 to prove her suspicions were correct — her husband was having an affair with an associate, Dr. Dean. She stole six love letters from his office desk while he and Dr. Dean were at a medical meeting. She spent that night at the home of Henry Kennedy and his wife, then confronted her husband with the letters. It was the first of several defections on the part of her husband, followed by pleas for forgiveness. Under cross-examination, she said her grounds for divorce were "cruel and inhuman treatment", meaning her husband's affair with Dr. Dean. Then, in what struck me as a laughable response, she explained she hadn't mentioned Dr. Dean in her divorce petition "for my daughter's sake." Yes, I'm sure a daughter would rather think her father was cruel and inhuman than in love with another woman. But she testified that within months of the divorce, she and Preston agreed to re-marry. She was asked to produce letters she received from her former husband while she and her daughter were in Panama, where this wedding was supposed to take place. She said she'd received letters, from him, but tore them up. In response, the defense produced letters from Dr. Kennedy to Dr. Dean. On June 26, 1933, just a month before he became fatally ill, he wrote:

Another letter, written in March on the day his divorce became final, Dr. Kennedy wrote to Dr. Dean suggesting a June wedding. But when June arrived, Dr. Dean was no longer interested in marrying him. On July 21, 1933, one week before the Kennedy brothers claimed their brother was poisoned by a woman who refused to let him go, Preston Kennedy wrote to Dr. Dean:

This supported the defense position that Dr. Dean had ended her relationship with Dr. Kennedy, and he was the one who didn't want to let go. When Dr. Dean finally took the stand on February 28, she testified that Dr. Kennedy threatened to kill her and himself if she tried to marry another man. The jury, if they remained awake, must have wondered when Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Dean had time for their patients. |

| The race card Oops! We've come to another detour. Dr. Dean's legal team, while obviously believing strongly in their client's innocence, must have sensed early on they were in trouble. Using whatever arguments they could muster, they asked for a mistrial during the opening hours of the trial, and three weeks later, when the state rested its case, moved for a directed verdict of acquittal, but were denied. However, the most defense's most desperate was made in response to the testimony of a 12-year-old black boy, whose job included cleaning rooms in Dr. Kennedy's medical building. His testimony conveyed more innuendo than evidence, but objection from Dr. Dean's attorneys was more about the race of the witness than what he said. Like much testimony in this trial, the statements of this witness, Bertie Leflore, well known as "Toodledums", could be taken two ways. Leflore said that on the morning of July 28, 1933, after the alleged rendezvous of Doctors Dean and Kennedy, he found two glasses and noticed a "rumpled sheet" on the examination table. Some took this to mean Dr. Kennedy had sex with Dr. Dean, in addition to drinks; others thought Dr. Kennedy lay down on the table when he returned to the office to pump his stomach. The first interpretation would suggest the pair were still engaged in their affair. If so, where was Dr. Dean's motive to poison her lover? On the other hand, Dr. Dean said she wasn't with Dr. Kennedy that evening, which suggested something else. When Dr. Dean was cross-examined after she testified several days later, she mentioned the name of another woman Dr. Kennedy was seeing. I was surprised her lawyers didn't try to throw that woman under the bus, but their position was Dr. Kennedy killed himself, either deliberately or accidentally, and his brothers, with cooperation from his ex-wife, were simultaneously out for revenge on the woman they blamed for breaking up Preston Kennedy's marriage, and collecting the best settlement possible from an insurance company. But since Dr. Kennedy bounced so crazily from wife to lover, why couldn't he have another girl friend? Anyway, it wasn't what Bertie Leflore said that upset Dr. Dean's attorneys, though I suspect Richard Denman's closing remarks on this subject were little more than a sorry tactic to win over the jury: "The state trimmed its sails in this case when they brought to the witness stand Toodledums. If you don't already resent that colored man's appearance on the witness stand, testifying against the character of a white lady, then you are failing to resent an attack on the womanhood of Leflore County. It is a desperate undertaking indeed when they have got to call a person who left Dr. Kennedy's office at 5 o'clock and didn't return there until next morning to make insinuations from the witness stand against the morals of a white lady. |

| Time for mail call While several letters were made public before the trial ended, they represented only a sampling of the many written to Dr. Dean by Dr. Kennedy, and vice versa. There also were letters written to Dr. Dean by Franklin C. Maull, her alleged fiancé, whose handwriting was often impossible to decipher, though one letter that was clear was much more significant than the prosecution, the jury, and Maull himself ever acknowledged. Judge Davis, correctly anticipating spectator reaction, announced it was okay to laugh when the letters were read, and I imagine he joined in, though Dr. Dean was probably embarrassed by several of her missives. For example, on January 1, 1933, she wrote,

But there it was — another reference to Dr. Kennedy being sick. The previous April 18, he had written this to her:

|

| Elephant in the courtroom Movies about trials often feature an off-the-wall witness who stuns the judge, jury and attorneys with testimony out of left field. There was such a witness near the end of Dr. Dean's trial, but his damaging testimony about Dr. Kennedy didn't seem to make much of an impression on the people who mattered. Dr. John Martin of Pope, Mississippi, describing himself as "just a country doctor", testified that he and Dr. Kennedy were school mates. He referred to Dr. Kennedy as "The Don Juan of the Delta Country." "But he didn't graduate from the Memphis Medical School we attended together. He received a mail order diploma from an Illinois institution." A prosecution objection prevented Dr. Martin from mentioning Dr. Kennedy's drinking when he was a student, but was allowed to testify he'd seen Kenned drunk in recent years and that "on one occasion, I suspected him of taking a narcotic to steady himself because of the liquor." According to a February 23, 1934 United Press story about the trial, Dr. Martin testified of Dr. Kennedy, "I never saw him that I failed to smell liquor on his breath." Dr. Martin said he and Dr. Kennedy once were called into consultation on a lawsuit at Coffeeville “but Dr. Kennedy was too drunk to discuss the case intelligently.” Prosecutors either were unprepared for Dr. Martin's testimony, or couldn't rebut it, and decided to treat him as someone not worth challenging. |

Prosecutor Witty outwitted Confronting Dr. Dean with a letter she had written to Preston in which was enclosed one from Captain Maull, Witty asked, "Was that fair to Captain Maull?" "Yes. Dr. Kennedy had shown me letters from a woman named Jody." "So you loved two men at the same time?" "An unfortunate situation," she replied, "but true." "Enough to marry both?" "No, only one." Witty then demanded to know why Dr. Dean did not attempt to see Dr. Kennedy while the surgeon was sick in the Baptist Hospital at Jackson where he died, allegedly from the effects of a poisoned whiskey highball." "I thought he was just getting over a spree or something," she replied. "Dr. Dean, why is it you are the only one who knew Dr. Kennedy to be so dissipated?" "As a matter of fact, two others who have been on this stand for the state could have testified to his drinking." "Yes? Who are they?" "Dr. Baskerville, Dr. Dickens, and I could also include yourself." Pow! Knock out win for Dr. Dean, who suckered Witty into making a classic lawyer mistake — he asked a question without anticipating the answer. But he got away with it. The jury must have been asleep. |

What a swell guy! As one of her attorneys, J. J. Breland, reminded the jury in his closing remarks, "She has flatly denied on the stand she kept the rendezvous. She has told you she was at home that night preparing her trousseau to wed another lover, Captain Franklin C. Maull."

Perhaps the wedding was wishful thinking. The woman was in her 30s, but had little experience with men. She produced a letter from Maull that referred to their August 8 date in Washington, but it's likely he didn't have a wedding in mind. Dr. Kennedy's death and her arrest prevented her trip, and it appears that when Maull learned of her problem, he backed off immediately. He visited her once between her arrest and trial, but told her he would not agree to testify on her behalf. When the trial began, reporters tracked Maull down in Lewes, Delaware, and he told them marriage was never discussed with Dr. Dean, so the jury couldn't help but conclude her alibi about preparing her trousseau on July 27 was a lie. More likely, Maull was the liar. Here's the thing: Today you see, hear and read about hundreds of emails exchanged between people on the days leading up to a crime. Back in Dr. Dean's time, people exchanged real letters, and she was able to produce more than hundred she had received from both Dr. Kennedy and tug boat captain Maull. A letter Maull wrote to Dr. Dean in July seemed to support her story, at least to the point she and Maull were to meet in Washington, D. C. on August 8. "We will leave Washington for Canada to stay as long as you like," he wrote. Maull was a pilot who had his own plane; perhaps he intended to fly her to Canada. Back home in Lewes, Maull told a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter that Dr. Dean was "just another girl friend, and no more. A single man has lots of girl friends. He sees some of them for awhile, and then they disappear. Well, I was unfortunate enough to have one that got in a lot of trouble." My guess is Maull was serious about the Washington and Canada trip, perhaps dangling marriage as a possibility. Or perhaps a wedding was merely an excuse Dr. Dean used to hide the fact she was going away for a few days with a man, and they'd obviously stay with each other, something proper unmarried women didn't do in 1933. And why marry in Washington, and not Mississippi or Delaware? There was something she wasn't admitting about the trip, but I believe she may have hoped it would lead to an elopement, which, at the time, would have been easy to arrange just out of Washington in Maryland, where you could check in one day, get married the next. Maull claims, probably truthfully, he'd never heard of Dr. Kennedy until the man's death resulted in the arrest of his girl friend. Suddenly any trip with Dr. Dean no longer was a good idea. He contacted a lawyer, perhaps worried that since Dr. Dean announced they were getting married, she may have prepared a trousseau as her first step toward filing a breach of promise suit, all the rage in the 1920s and early '30s. I think Maull was a would-be playboy who suddenly felt the need to distance himself from Dr. Sara Ruth Dean and concentrate on his other girl friends. I don't know if this was a factor, but as far as I've been able to determine, Franklin C. Maull was 27 or 28 at the time of the trial. He must have known he was younger than Dr. Dean, but until the trial, her age was listed at 33 years old. Turns out this was a lie she'd been telling for many years. She admitted during testimony that she was born in 1898, not 1900. That she actually was eight years older may have bothered Maull, or perhaps he worried she might be lying about other things. But her sudden notoriety probably bothered him most of all. One wonders if Dr. Dean later considered herself lucky she never became Mrs. Maull, especially in December, 1935, when, according to a short Associated Press item that appeared in several newspapers, Maull purchased a tiger cub, and as he was taking it to shore in a small boat, the cub escaped. It was presumed drowned, but days later, Lewes residents reported seeing the tiger cub on the beach; there also were reports several cats were missing, presumed killed by the tiger cub. Maull eventually got married, sometime after the 1940 census was taken, and his wife, the former Marie L. Darrah, died in 1966. They had a daughter who got married in 1965. When Maull died, I don't know. I haven't found his obituary. Back to the trial: |

|

While the jury may not have regarded her as a fiend, they found Dr. Dean guilty after nearly fourteen hours of deliberation. According to the journalists who ventured an opinion, the verdict was a surprise. Grace Robinson's reading of spectators was they also were surprised, believing the defense attorney had made a strong argument against a rather flimsy, circumstantial case. As senior defense counsel, A. F. Gardner put it after the verdict came in, "The only thing Ruth Dean is guilty of was loving a worthless man," referring to Franklin C. Maull. But that wasn't the end of the story. In what many felt was an unusual decision, Judge S. F. Davis allowed Dr. Dean to remain free on a $10,000 bond pending the outcome of an appeal to the state supreme court. As far as Dr. Dean was concerned, she wasn't headed for jail, and while she'd said little during the trial, she opened up a bit afterward, and granted at least one interview. Here is how that story began: |

|

|

|

I suspect Judge Davis disagreed with the jury's verdict, but didn't feel so strongly he was willing to overturn it, but instead wanted the state's supreme court judges to review the case. He may have been surprised 13 months later when the supreme court upheld the guilty verdict. But Dr. Dean and her lawyers weren't done fighting. They appealed to Mississippi Governor Martin Sennet Conner, and he temporarily suspended her sentence while he considered her case, and on July 8, just before Dr. Dean was due to be transported to In issuing the pardon, however, Governor Conner added mystery to the already mysterious death of Dr. Kennedy. Conner said he "had the benefit of information not available to the courts either in the original trial or on appeal" to the state Supreme Court. He never revealed what that information contained, though anyone looking at this case today might wonder why Dr. Dean was ever charged, let alone convicted. The New York Sun reported the only testimony given at the governor's hearing was by Sam Osborne, a friend of Dr. Kennedy, who talked to the governor in private, which strengthened the defense argument Dr. Kennedy either lied about the poisoned highball or his brothers fabricated the story of a death-bed statement. For Dr. Dean, she remained free for the rest of her life, though, technically, she was still a convicted murderer, which may have helped Mrs. Kennedy collect the maximum amount of life insurance on her husband. That was one of those thing often forgotten by the press and settled without fanfare. As I said, that was a Solomon-like decision by the governor. Bessie Barry Kennedy and her daughter moved to Jackson. As far as I can determine, Mrs. Kennedy never re-married. Her daughter, Annie Margaret Kennedy attended Mississippi University for Women, then earned her B. A. degree cum laude in 1950 from Millsaps College. She married William D. Morrison Jr., a Jackson architect, and joined the staff of the the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, later resigning to raise four sons and a daughter. She died in 2007, at the age of 78. Dr. Ruth Dean (her first name discarded) spent 21 years at the Mississippi State Hospital in Whitfield as resident doctor, but also practiced for awhile at children's hospitals in Boston and Denver. Grace Robinson might have been interested to know that at the time of her death, in 1970, Dr. Dean was a member of Forest Grove Presbyterian Church in Canton, Mississippi. She eventually was married, to widower Marshal N. Pitchford, who died in 1958. When Dr. Ruth Dean Pitchford passed away 12 years later, she was survived by three sisters and an aunt. |

|

| HOME • CONTACT | |

proceedings was stunningly sexist and grossly unfair, though it may have expressed a popular view of the accused.

proceedings was stunningly sexist and grossly unfair, though it may have expressed a popular view of the accused. Sara Ruth Dean presented a challenge. Seldom described as "beautiful", she more likely was called "handsome" or "comely", which despite what you may find in a dictionary or thesaurus, is akin to saying, "but she has a great personality!" Otherwise she was called "attractive", "the woman with the tragic face", "statuesque", and "cameo-faced." (For the first four weeks of the trial she remained remarkably calm, almost stone-faced, then she became ill and spent one day crying in court.)

Sara Ruth Dean presented a challenge. Seldom described as "beautiful", she more likely was called "handsome" or "comely", which despite what you may find in a dictionary or thesaurus, is akin to saying, "but she has a great personality!" Otherwise she was called "attractive", "the woman with the tragic face", "statuesque", and "cameo-faced." (For the first four weeks of the trial she remained remarkably calm, almost stone-faced, then she became ill and spent one day crying in court.) I've never been sure of what constitutes blonde hair, but in photos, Mrs. Kennedy's hair seems rather dark. And the image of Dr. Kennedy presented in trial was far from dashing, with his letters making him sound like a school boy in the throes of his first crush. Dr. Dean, described as gifted here, was often called "brilliant," though I'm not sure why, given the way she carried on with a morphine-loving adulterer.

I've never been sure of what constitutes blonde hair, but in photos, Mrs. Kennedy's hair seems rather dark. And the image of Dr. Kennedy presented in trial was far from dashing, with his letters making him sound like a school boy in the throes of his first crush. Dr. Dean, described as gifted here, was often called "brilliant," though I'm not sure why, given the way she carried on with a morphine-loving adulterer.  That's right. The woman described by Herbert Asbury near the beginning of this piece as "man hater" claimed she'd had two lovers — Dr. J. Preston Kennedy and a Delaware tug boat captain named Franklin C. Maull. She planned to leave Greenwood on August 6 to board a train for the nation's capital and her wedding.

That's right. The woman described by Herbert Asbury near the beginning of this piece as "man hater" claimed she'd had two lovers — Dr. J. Preston Kennedy and a Delaware tug boat captain named Franklin C. Maull. She planned to leave Greenwood on August 6 to board a train for the nation's capital and her wedding. prison, he pardoned the doctor, insuring she had made good on her promise to never serve a day of her life term.

prison, he pardoned the doctor, insuring she had made good on her promise to never serve a day of her life term.