| HOME | FAMILY | YESTERDAY | SOLVAY | STARSTRUCK | MIXED BAG |

|

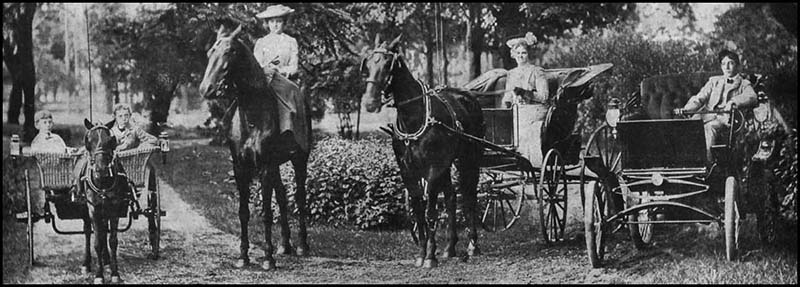

Part 12: I think the first question was answered by bank president Charles T. Beckwith of Oberlin after he confessed his financial involvement with Mrs. Chadwick to his board of directors and echoed his mea culpa to any reporter willing to listen. Beckwith probably felt worse when he learned most bankers who met the woman had turned her down when she asked for loans. No doubt, those men who agreed to give her huge amounts of money were swayed by the rather vague assurance of Iri Reynolds, a much respected and trusted Cleveland bank official, who, unfortunately for him, also was too trusting and respectful, believing the word of a woman who just happened to be married to a man who'd been Reynolds' friend most of his life. All Reynolds was actually telling other bankers is he was holding securities that Mrs. Chadwick claimed were worth several million dollars. He never said he'd made an attempt to verify Andrew Carnegie's signature on those documents. When they were finally examined in mid-December, 1904, the results were shocking, humiliating, and, to some, amusing. There were two documents — one a note promising $5,000,000, the other a trust supposedly worth more than twice that amount — backed by a forged signature of Andrew Carnegie. Both documents, of course, were worthless, though I imagine they'd fetch a good price today among collectors of forged signatures. The only thing worth any money was a note for $1,800 from Emily and Daniel Pine, payable to Cassie L. Chadwick, and a mortgage to secure the same. Emily Pine was one of Cassie Chadwick's sisters; she and her husband also lived in Cleveland and had two sons, who appear in a wonderful photo at the bottom of this page that shows Mrs. Chadwick, her son, Emil, and her stepdaughter, Mary. The boys are in horse-drawn cart, Mary is on horseback, Mrs. Chadwick in a horse-drawn wagon, and Emil in an automobile. The good life on display in the early 1900s. The discovery of the true value of Mrs. Chadwick's securities convinced Herbert D. Newton and the directors of Citizens' National Bank in Oberlin there was no chance they'd be repaid. (It was estimated that, at best, they'd receive 16 mills on the dollar, or less than two cents.) Because Newton had met Mrs. Chadwick through the pastor of John D. Rockefeller's church, the Massachusetts financier had the silly idea Rockefeller would cough up $190,800 out of some weird sense of responsibility. As far as I know, Rockefeller wasn't moved by Newton's foolishness. Carnegie did help certain depositors of the Oberlin bank, reimbursing college students and citizens who could ill afford to lose the money they had entrusted to the bank. |

| * * * |

A Friend indeed At first, Mrs. Chadwick denied any dealings with Friend, who simply refused to comment one way or the other. What was revealed — and speculated upon — over the next few years gave reason to believe Mrs. Chadwick may have borrowed $2,000,000 or more during her marriage to Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick, whose involvement in her scheme became more and more suspect. Iri Reynolds said the doctor knew everything about his wife's dealings, but Dr. Chadwick, like Sgt. Schultz of "Hogan's Heroes," kept repeating, "I know nothing! know nothing!" and when his wife was hauled off to jail, he and his daughter remained in Europe, traveling from Paris to Brussels to Berlin, before finally sailing for the United States in late December. Of all Mrs. Chadwick's dealings, those with Friend may be the most interesting. It appears they were trying to outplay each other, and while I have to believe he was suspicious about her Carnegie-supported "securities," he was willing to take a chance they were genuine, because that might give him an opportunity to grab millions of Carnegie's dollars should his illegitimate daughter fail to repay her loans. |

|

|

|

It wasn't quite that simple. Actually, there were six different loans over a year that totaled $798,200, and while the stories about the dealings between Mrs. Chadwick and Friend said the man had been duped, I believe he was simply gambling that she might have been telling the truth about her securities, but that she'd be unable to repay the loans, and he'd come into possession of all the millions promised by Carnegie. Friend and his partner, Frank N. Hoffstot, had operated in similar fashion earlier with William C. Jutte, a millionaire coal operator who needed loans along the way, and when Jutte couldn't repay one of them on time, Friend and Hoffstot seized the man's estate estimated to be worth several million dollars. Jutte responded by killing himself in an Atlantic City hotel on May 25, 1905. He'd tried once before, in 1901, and even though he shot himself in the head that time, he survived. The second time he shot himself in the chest. His widow would involve Cassie Chadwick in an unsuccessful attempt to recover what was left of her husband's fortune. |

|

| * * * |

The great escape |

|

|

|

That window was on the seventh floor and gave her access to a fire-escape to an extension roof. Then she crossed the roof and walked along what the newspaper described as "a perilous ledge" until she reached a rear window of the adjoining building at 56 Wall Street. This building had a passage that let Mrs. Chadwick exit a block away on Pine Street, where she had arranged for a cab to pick her up. She escaped unseen and returned to the Holland House. (Two years later Evelyn Nesbit Thaw would make a similar escape from the press when she visited her lawyer the day after her husband shot and killed Stanford White.) A few days later, Mrs. Chadwick once more tried to escape reporters and the Secret Service agents who had been assigned to watch her. |

|

|

|

| About three hours later, Mrs. Chadwick was arrested, charged by the government with aiding and abetting a bank official in misapplying $12,500 from the Citizens' National Bank of Oberlin, Ohio. By the time she went to trial in March, she would face 16 separate charges. | |

|

|

Contrary to what some have written, Cassie Chadwick wasn't wearing a money belt containing $100,000 in cash when she was arrested. The whereabouts of her money remained an unsolved mystery, though it was suspected she may have used her son, Emil Hoover, then about 19 years old, to transport cash and jewels to Ohio before her arrest, but that was never proven. Mrs. Chadwick spent her first night as a prisoner at the Hotel Breslin, then was arraigned the next morning before U. S. Commissioner John A. Shields, then taken to the Tombs, where she remained until the evening of December 13 when she boarded a train for Cleveland, arriving there shortly after 11 a.m. the next day. One of the strange things Mrs. Chadwick did when she was booked at the Tombs was to say she was 51 years old, adding four years to her actual age at the time. No one seemed to notice what this did to her claim about being Andrew Carnegie's daughter. If she really were 51 years old in 1904, that would have made Carnegie 17 years old when she was conceived. Possible, of course, but even more unlikely than before. She may have realized the problem during her trip back to Cleveland, because when she was being booked at the Cuyahoga County jail, she claimed she was 38 years old. When she went to prison the first time (as Lydia Devere), she subtracted six years from her real age and told penitentiary officials she was 28 years old. Zsa Zsa Gabor had nothing on Cassie Chadwick. |

|

| * * * |

One in jail, the other at sea Near her, in a cell in the same corridor of the jail, was 21-year-old actress-dancer Nan Patterson, whose trial for the murder of bookmaker Caesar Young was sharing headlines with the Cassie Chadwick scandal. Ms. Patterson was a newlywed, but that didn't prevent her from having an affair with Young, who also was married — until he took a carriage ride with the performer and wound up dead of a gunshot. After one hung jury, Patterson was found not guilty in her second trial, but while she regained her freedom, she failed too cash in on her notoriety, and had a lackluster career. Young's killer was never caught; well, most observers thought the killer had been caught, but was let go by a jury perhaps swayed by the defendant's good looks. Meanwhile, attention shifted momentarily from Cassie Chadwick to her doctor-husband, who remained vague about when he and his daughter would return from Europe. Iri Reynolds and Charles T. Beckwith both insisted Dr. Chadwick was well aware of his wife's con game, but the doctor continued to make denials, though on December 22 a Cuyahoga County grand jury indicted him along with his wife on a forgery charge. By then Dr. Chadwick was headed home on the steamer Pretoria, expected to reach New York City on New Year's Eve. The Pretoria made it to New York on schedule; Dr. Chadwick, accompanied by the Cuyahoga County sheriff, got on a train to Cleveland, and Mary Chadwick, the doctor's daughter, headed for Florida to live indefinitely with her uncle, Bingham Chadwick. Dr. Chadwick arrived in Cleveland the next morning, on New Year's Day, and spent 90 minutes at the county jail visiting his wife: |

|

|

|

Later, Dr. Chadwick said, “All this trouble has come upon me with such suddenness that I am almost crushed. Of course, I am not guilty of any wrongdoing. For thirty-five years I have made Cleveland my home, and this is the first time there has been any taint on my name. It is too terrible. Even my home has been taken from me, and, if all reports are true, I am a penniless pauper.” For the doctor there was some good news mixed with the bad. While his house had indeed been taken possession of for the benefit of Mrs. Chadwick’s creditors, lawyers decided Dr. Chadwick cannot be barred from its use. For a little while, anyway. |

|

Happy days in Cleveland (though no one is smiling). Left-to-right: The two sons of Emily and Daniel Pine; the boys were Cassie Chadwick's nephews. That's Mary Chadwick on horseback; the daughter of Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick was about 18 when this photo was taken, the same age as Emil Hoover, Cassie Chadwick's son, who's in the automobile at the right. Between the two teenagers is Cassie Chadwick, aka Lydia Devere and many other aliases, who was born Elizabeth Bigley. |

| HOME | CONTACT |