| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

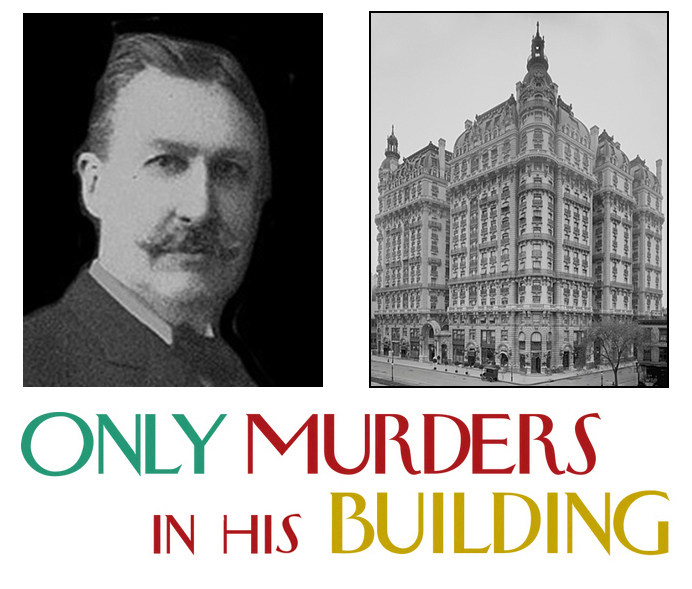

William Earl Dodge Stokes Sr., (above), better known by the initials in his first three names, was quite a character way back in the day, but long forgotten until the success of the Steve Martin-Selena Gomez-Martin Short comedy series on Hulu, "Only Murders in the Building." The program's building is called the Arconia, an apartment complex on the West Side of New York City. The actual building shown in the series is the Belnord, built in 1908 and spanning an entire block on 86th Street between However, I can't help but think that in real life, the Arconia is the Ansonia, a West Side hotel built by W. E. D. Stokes, and one of its original residents when it opened in 1904. Construction started in 1899, but was often delayed, partly because Stokes insisted on supervising. The hotel was finished 18 months later than planned, and Stokes went over budget by about $1 million, an incredible amount at the time. He named the hotel Ansonia after his maternal grandfather, Anson Greene Phelps, who founded a Connecticut town by the same name. When it opened, the Ansonia was the biggest, fanciest hotel in New York City, the first to be air conditioned. (What may have been the only murder in the Ansonia occurred two years after it opened. Dead was Al Adams, one-time king of the New York City numbers racket. Adams resided in a suite at the Ansonia. City coroner Julius Harburger thought Adams was murdered, and set out — in vain — to prove the crime was committed by Stokes. Finally, it was decided Adams committed suicide.) Among other Ansonia residents over the years were composer Igor Stravinsky, conductor Arturo Toscanini, opera star Roberta Peters, and baseball legend Babe Ruth. The building was converted to condominiums in the 1990s. MY INTEREST in W. E. D. Stokes began about 20 years ago while, for no reason that I can remember, I researched newspaper stories from 1921. Then, one day, I came upon this: |

|

Naming his own son as a corespondent in a divorce was highly unusual, and I had to find out more about the husband involved. As the story said, W. E. D. Stokes had a spectacular past. In several ways, Stokes reminded me of Donald Trump. Both inherited fortunes from their father, made their livings through real estate and were sociopathic womanizers. It was at the Ansonia that Stokes lived for awhile with his second wife, the former Helen Ellwood (whose last name variously appeared both with one L and two). Their relationship ended with what was considered the dirtiest divorce of its time, perhaps of all time. That a man would name his son as Though she had much more evidence on her side, had she chosen to smear her husband, Mrs. Stokes held the high ground throughout an incredibly long case that — like a car spinning its wheels in mud — made lots of noise and splattered lots of people, but wound up where it started. Like Trump's election fraud cases, Stokes' efforts to divorce his wife failed to convince judge or jury. Stokes' lawyers may have been delighted at the prospect of a big pay day, but some of them had to take him to court to collect what he owed. They were lucky to get 75 cents on the dollar. Another reminder of Donald Trump. AS FOR Helen Ellwood Stokes, she must have been transformed during the eight years she and her husband lived together, because it hardly seems possible the woman, who gave better than she got during cross-examination by one of the country's best lawyers, could be the same person foolish — or greedy — enough to marry W. E. D. Stokes, who was 34 years her senior. It's possible, of course, that she simply outfoxed her husband and was an excellent actress. It was 1910 when Helen Ellwood moved into the Ansonia as the guest of her sister and her husband, Dr. and Mrs. Wilbur A. Hendryx. Stokes pursued the 23-year-old woman, and on February 11, 1911, talked her into getting married in Jersey City, New Jersey. A college classmate of Stokes performed the ceremony. She was puzzled when he insisted they get married secretly and why he listed his age as "over 45" on the marriage license. (He actually was 58.) Likely she knew about two notorious affairs he recently had with women younger than herself, yet Helen Ellwood went through with the marriage.

THOUGH Stokes was not attractive, his wealth guaranteed some luck with the ladies. He was born into a prominent New York City family in 1852, son of James Boulter Stokes and Caroline Phelps Stokes. He had three brothers, Anson Phelps Stokes, James Boulter Stokes Jr. and Thomas Stokes, and four sisters, Elizabeth, Dora Lamb, Olivia and Caroline. He considered himself well-bred and better than most people. (In 1916 he would write a book, “The Right to be Well Born: Horse Breeding in its Relation to Eugenics,” suggesting the solution to many of our problems is good breeding. He endorsed the idea of sterilizing defective humans. Not surprisingly, few people read the book, which placed Stokes alongside Adolf Hitler; they had similar views on a master race.) I found little about Stokes' sexual escapades before he flipped for Rita de Acosta, but there must have been several. However, his relationships after their divorce are well known. In 1902, while taking a ride in his carriage, the 50-year-old born-again bachelor was flagged down by a pretty young woman who was leaning out of her bedroom window. That marked the beginning of Stokes' tawdry five-year affair with Lucy Ryley (later known as Lucy Randolph). In 1907, she sued Stokes for child support, claiming he was the father of her four-year-old son. Stokes, a veteran of countless court battles, won this one on a legal technicality. What happened afterward to the woman and her son is unknown. In 1906, John Singleton, millionaire and partner in the gold-rich Yellow Aster mine in California, checked into the Hotel Ansonia with his wife, Stella Graham Singleton and her eighteen-year-old sister, Lillian. Stokes wasted no time introducing himself to the teenager. Thus began another affair, one that eventually would lead to the wildest night of Stokes' life. FOUR MONTHS after marrying Helen Ellwood, Stokes made an effort to retrieve embarrassing letters he wrote to Miss Graham, by then an aspiring singer and dancer who shared an apartment with Ethel Conrad, a would-be actress who may have used her roommate's letters to concoct a blackmail plot against Stokes. What happened next is the kind of stuff that inspired Hollywood's screwball comedies. In some ways it resembles "Roxy Hart" and the subsequent musical, "Chicago." Stokes visited the women's to apartment to retrieve his letters. He told police later that both women confronted him and demanded $25,000 for the letters. The women told a far different story. Both Graham and Conrad had purchased revolvers and insisted they had to use them on Stokes in self-defense. He was hit three times in his legs, but suffered no life-threatening wounds. He wound up in a hospital, the young women went to jail ... but a day later they were bailed out by an enterprising vaudeville promoter who immediately booked them as New York City's latest act. STUNNED and hurt by all this was the new Mrs. Stokes, who would, for the moment, stand by her man when this case went to trial. But she must have known she and Stokes were going to have a miserable marriage. As for Graham and Conrad, they had a short unsuccessful vaudeville career and now are merely answers to a trivia question. But even before the shooting incident, the second Mrs. Stokes knew she wouldn't stick with her husband until death parted them. While the Ansonia was a fancy hotel, something was amiss on the roof. That where Stokes had a farm and several animals, including enough chickens to supply hotel tenants with eggs. This violated a city ordinance, and after one false start, the city eliminated the farm, but soon Stokes bought more chickens and kept them in his apartment, much to the displeasure of Helen Stokes. Eventually, Mrs. Stokes convinced her husband to leave the Hotel Ansonia, which she felt was not a proper place to raise children. The family moved into a house a few blocks away, but their marriage went from bad to worse, and on New Year's Eve, 1918, Mrs. Stokes went out for the evening with her visiting second cousin, Hal Billig, her husband begging off on account of illness. Mrs. Stokes and Billig returned later than Stokes thought appropriate. Feelings of jealousy and resentment spilled out in a three-way argument that, in effect, put an end to the marriage. Billig checked into a hotel that evening, Stokes moved back to the Hotel Ansonia – by himself. And Mrs. Stokes and the children moved to Denver and lived with her mother. IT TOOK two years before W. E. D. Stokes filed for divorce. His wife filed for separation and also claimed her husband had conspired to deprive her of her dower rights.

They may have felt even sorrier for her when she testified about the poultry farm Stokes had maintained in his apartment at he Ansonia Hotel. She said there were 45 hens and several roosters in this collection, and that their presence in the apartment constituted such a nuisance that she was frequently unable to eat there. She described the place as “absolutely filthy.” Stokes employed a private detective from Chicago to dig up evidence that before their marriage, Helen Ellwood had worked as a prostitute in the Windy City. He also paid a New York City detective to link her with a murderer. Martin Littleton, lawyer for Mrs. Stokes, convincingly discredited every witness who even hinted that his client was guilty of nefarious behavior. Those who covered the 1921 trial felt that Mrs. Stokes was her own best weapon. During questioning about a November 20, 1916 physical encounter with her husband, she displayed a refuse-to-be-intimidated attitude that prevailed over her husband's lawyers throughout their courtroom battles. Herbert C. Smyth, attorney for Mr. Stokes, asked: “Isn’t it a fact that you injured your husband that day and that he was laid up for five days with the wounds you inflicted?” “Oh, no, but I defended myself when he choked me.” Mrs. Stokes answered. “How?” “With all I had, my hands and fingernails, I guess.” “You scratched him good and plenty, didn’t you?” “I hope I did.” SEVERAL WEEKS after testimony concluded, Justice Edward R. Finch of New York Supreme Court finally announced his decisions: He denied the application of W. E. D. Stokes for a divorce and granted the application of Mrs. Stokes for decree of separation. The children of the couple would remain with their mother. Unfortunately, this was far from the end of Stokes vs. Stokes. The alimony question was left hanging by Judge Finch, contributing to a legal technicality that forced a rematch in 1923 when Mrs. Stokes' suit for a separation would be heard separately – and heard only if her husband again lost in his divorce bid. And this time a jury would decide. Which meant the eminently unlikeable W. E. D. Stokes didn't have a chance. Though Stokes hired one of New York's finest lawyers, Max D. Steuer, to handle the second attempt at a divorce, his case got off to a bad start when Steuer's "star witness," Mrs. Emma E. Goodwin, a corset manufacturer whose shop was located at the address where Edgar T. Wallace, alleged corespondent, had his apartment. Mrs. Goodwin identified Mrs. Stokes as the woman who frequently visited Wallace, but she made the mistake of saying the woman was "either Mrs. Stokes or her double." Mrs. Stokes' new lawyer, Samuel Untermyer, produced a woman, Mrs. Margaret Pell, who, indeed could have been his client's double and also frequently visited Wallace. For Stokes, things went downhill from there. After the testimony and closing arguments, it took a jury just 68 minutes to reach a verdict — in favor of Mrs. Stokes, who planned to countersue for separation. Four days later W. E. D. Stokes gave up without a fight against his wife's separation suit. It seemed a wise decision, since his unsuccessful litigation had already cost more than $1,000,000. At least, that's what he had been charged. What he actually paid his lawyers was considerably less. STOKES died in 1926. He was 73. In his will he left his entire estate to his son, W. E. D. Stokes Jr. That estate was estimated at $7,000,000. The will made no mention of Helen Ellwood Stokes or her children. Mrs. Stokes contested the will and the case was settled out of court. The disinherited children were to receive $3,000,000 worth of property when they became of age. Mrs. Stokes received $156,500 for her services as guardian of the children. She and her children settled in Denver. What eventually happened to them I do not know. |

| HOME | CONTACT |

Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. Its most famous feature is its archways leading to an interior courtyard. Inside the building are 200 apartments.

Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. Its most famous feature is its archways leading to an interior courtyard. Inside the building are 200 apartments. corespondent may have attracted my attention, but what held it was the depth to which Stokes sank in his efforts to have his wife declared an adulteress unfit to be given custody of the couple's two children. (Stokes asked his first-born, W. E. D. Stokes Jr., known as Weddie, to claim he had sexual relations with his stepmother, and later paid other witnesses to lie about Helen Ellwood Stokes in court.)

corespondent may have attracted my attention, but what held it was the depth to which Stokes sank in his efforts to have his wife declared an adulteress unfit to be given custody of the couple's two children. (Stokes asked his first-born, W. E. D. Stokes Jr., known as Weddie, to claim he had sexual relations with his stepmother, and later paid other witnesses to lie about Helen Ellwood Stokes in court.) Stokes had been married once before, when he was 43 (and that time shaved eight years off his real age on the marriage license), In truth, Stokes never got over wife number one,

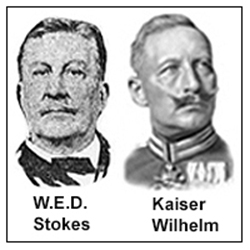

Stokes had been married once before, when he was 43 (and that time shaved eight years off his real age on the marriage license), In truth, Stokes never got over wife number one,  During the trial, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle put into print something that already occurred to people – W. E. D. Stokes bore a striking resemblance to Germany's much despised Kaiser Wilhelm. The headline said it all: "Stokes Resembles Kaiser, Spectators Sorry for Wife"

During the trial, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle put into print something that already occurred to people – W. E. D. Stokes bore a striking resemblance to Germany's much despised Kaiser Wilhelm. The headline said it all: "Stokes Resembles Kaiser, Spectators Sorry for Wife"