| HOME |

|

|

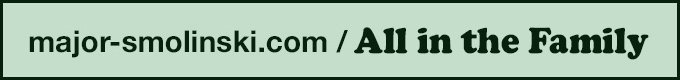

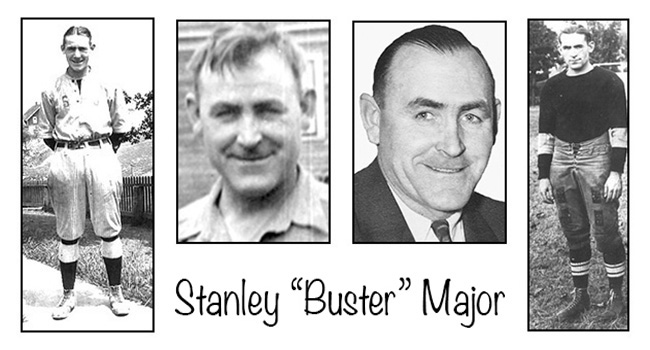

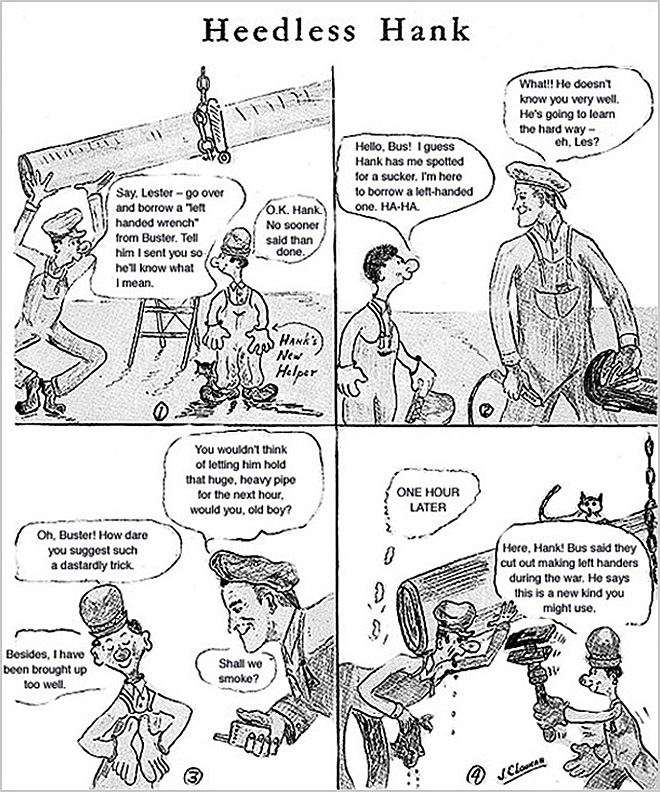

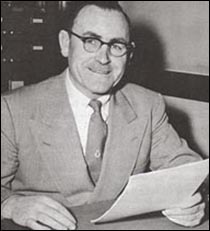

Prankster-playing athlete ran He was a star athlete, first at Solvay High School and later at Christian Brothers Academy in Syracuse. He played basketball, but his best sports were football and baseball. From the newspaper clippings I've read, my father came across as a high school version of Jim Brown. He was a running back who was bigger than most of the linemen he played against. And like Brown did at Syracuse, my father kicked extra points. There was even a mention in a Syracuse newspaper of a game in which Buster Major dropkicked a field goal. After leaving CBA in 1924 he received a scholarship at Dean Academy in Franklin, Massachusetts. While playing at CBA he had been scouted by Chick Meehan, then the head football coach at Syracuse University. Meehan left Syracuse to become the football coach at New York University in 1925. Buster's plan was to play football at Dean Academy in 1924, then attend NYU and play for Meehan there, but a knee injury sidelined him at Dean, and afterward he was considered damaged goods. His ultimate dream was being a major league pitcher, but he was not as effective after his knee injury, though continued to spend summers pitching, perhaps too much. He often pitched two games on the same day, for different teams in leagues where he might be playing under another name. That was never the case on two of his teams — the Solvay Tigers and the Major All-Stars (comprised mostly of Major cousins from Skaneateles). BUSTER MAJOR also was a prankster whose antics inspired a comic strip character (below) in a Solvay Process Company publication. Like many pranksters, Buster Major loved to perform. Sometimes he did it on stage, along with other Solvay residents in the annual minstrel shows produced by St. Cecilia's Church. However, he did it most successfully during his 1949 mayoralty campaign. He campaigned almost playfully, believing he didn't have a chance of winning, but his style proved popular. Most memorable were his song parodies, especially the campaign song he wrote to the tune of The Missouri Waltz, chosen because Missourian Harry S. Truman had pulled a stunning upset the year earlier in defeating Thomas Dewey for president. (See the Buster Major Election Songbook, below.) Buster sang those songs at the several rallies — i.e., free beer, everybody! — that the Democrats held at various clubs. Buster and his running mates were perhaps the first Syracuse-area candidates to use television, buying time for (I believe) two programs in 1949. He won the election, and two years later was re-elected by a convincing margin. (See his election results, below.) Onondaga County was — probably still is — overwhelmingly Republican. So Buster quickly became the county's most successful Democrat. The party wanted him to run for Congress, but he declined. He did, however, make a bid for the State Assembly, but lost. Being mayor of Solvay was a part-time job. His full-time job for many years was at the Solvay Process Company. For the 12 years he was mayor he was busy for at least part of almost every weeknight. He made it a point to attend every wake in the village and several in nearby communities. HE WAS an avid sports fan who attended almost every Syracuse University football home game for many years. My favorite memory was when he rushed to the field after a game in order to intercept a player for a remarkable performance. I don't recall the opponent or the score, but the game was during that period of the 1950s when colleges briefly returned to one-platoon football. The player on the receiving end of Buster's handshake was Ted Kukowski, a center and linebacker who seemed to be in on every tackle. Buster also was a huge boxing fan, which is why my childhood Christmas gifts included boxing gloves and a punching bag. Occasionally he met with his political cronies at our house. The meetings always adjourned in time to catch a televised fight. As much as he enjoyed the spotlight, he may have been just as happy alone. He looked forward to our vacations and being able to escape for hours to go fishing by himself. (See Sandy Pond.) WHEN IT CAME to food he was notoriously fussy. He wanted his hot meals super hot. Not spicy. Hot! He also ate his food quickly. His jaw moved over cooked food the way a person in bare feet would move over hot coals. So while our family was together when dinner started, there was one member missing before the meal ended. Buster's love of fish got him through the meatless Fridays that were part of Catholic life for many years. However, he preferred meat. So as a late-night person, Buster could be found in the kitchen at the stroke of midnight (sometimes a minute or two earlier) making himself a ham sandwich to eat while watching Jack Paar, then later Johnny Carson. He had strong opinions, but seldom tried to force them on his children. He did, however, enjoy a good argument, particularly about politics. For a politician, he was refreshingly candid, though his remarks sometimes resulted in a lecture from his wife, Helen, who always waited until they were alone before she delivered it. He started smoking when he was in high school. Chesterfields was his cigarette of choice. His smoking convinced me not to use cigarettes because I thought they were the cause of his persistent cough, though he claimed it was due to a bout of bronchitis while he was growing up. (He probably was correct; I've had the same cough since I had bronchial pneumonia in my early 30s.) He finally kicked the smoking habit, though his method was unusual. As a St. Cecilia's parishioner, he came to appreciate Rev. Carl Denti, who may be listed in the Guinness Book of Records for saying the world's fastest mass. So when, as mayor, Buster was introduced to a priest who had recently been assigned to the church, he greeted him with, "Pleased to meet you, Father McCarthy . . . you know, your masses run a bit long." BUSTER'S PATERNAL grandparents were William Major and Mary Anne O'Neil, who married in Ireland in 1865, connecting the Major family with the famous O'Neil clan and The Legend of the Red Hand. The couple emigrated to the United States shortly thereafter and settled in Skaneateles, NY. Buster's father was John W. Major (1870-1940), one of 10 children of William and Mary Anne Major. His mother was Rose McLaughlin (1872-1943), one of four children of John and Mary (Casey) McLaughlin. John W. Major also was an avid Democrat who was involved in politics at a local level. He served two terms as trustee in the village of Solvay (1910-14). Buster married Helen Smolinski in 1929 and for most of their life together they lived at 104 Russet Lane. They had two children, John Stanley Major (1938- ) and Mary Elizabeth Major Chard (1943-2018 ). |

|

|

For years I assumed my father was nicknamed "Buster" because it had something to do with sports and his physique. He was a bruiser in high school, barrel-chested and bigger than most of his classmates, and he was a fullback on the football team. I imagined that when he was a toddler, people would look at him as say, "He's a buster!" But when I finally got around to asking him how he got the nickname, he simply answered, "Buster Brown." And I thought he had to be kidding, because, to me, Buster Brown the name of a shoe. Certainly my father couldn’t have been nicknamed after the girly-looking kid featured — with his dog — in the shoe company’s label. The company's radio commercials featured the voice of a child actor who made popular the phrase, "I'm Buster Brown, I live in a shoe. That's my dog, Tige, he lives there too!" Then I became aware of a line of Buster Brown clothes for young boys, outfits that seemed designed for a 17th century prince. My image of Buster Brown certainly didn't fit my image of my father. Whoever dubbed my father "Buster" must have been very cruel indeed. Finally, a few years ago, I became aware of the Buster Brown comic strip that began in 1902, the year before my father was born. I learned that, despite his Lord Fauntleroy appearance, Buster Brown was a bit of a smartass who enjoyed playing practical jokes, and always had a quick excuse for his behavior. — JACK MAJOR |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| – JACK MAJOR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| HOME | CONTACT |

Campaign '49:

Campaign '49: