| HOME |

|

|

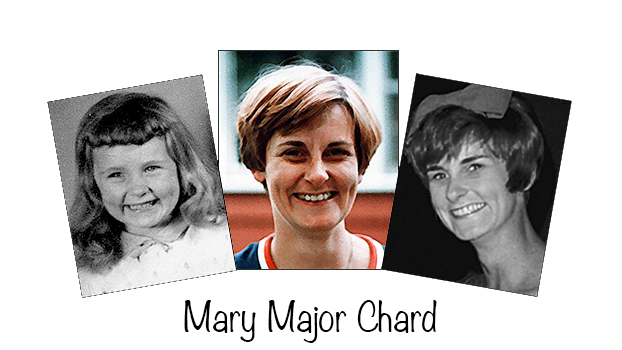

Some of her friends were invisible We consoled ourselves that it's common for a child to have a make-believe friend with a goofy name, but Mary Beth had three such pals – Mickerbeek, Mickerbock and Shiny. They helped make Mary's pre-school life weird enough to inspire a Dakota Fanning movie. Because our family assembled mostly around the dinner table, it was during meals that Mary Beth would report the latest antics of her imaginary buddies. If Mary Beth's behavior that day had been exemplary, credit Mickerbeek's influence. If Mary Beth had been naughty, blame Mickerbock. If she had gone beyond naughty into a Category Four holy terror, then summon Father Shields from St. Cecilia's Church ... because Shiny had taken control of our little Mary Beth. IT MUST have been Shiny's fault when Mary Beth ran away from home. As I recall, she did it hobo style, carrying a bundle of clothes on a stick that rested on Mary Beth's shoulder like a rifle. She had probably just turned five – such a liberating age – when she marched down Russet Lane, turned left on Orchard Road and headed for the bus stop at the bottom of the hill on Milton Avenue, across from the Solvay Process Company. A bus to Syracuse came along about every half-hour. It was the left turn on Orchard Road that tipped my mother and me that Mary Beth didn't really intend to leave us for good. Maybe she was just outsmarting Shiny, who might not have realized we always used a different bus route and a closer stop, to the right, a short block away on Woods Road. I suspect Mary Beth hoped she'd run into my father who might be walking up Milton Avenue on his way home from work. He'd make right whatever was bothering her.

IT WAS the 1940s and one of our house rules was to eat everything on our plates because (say it with me, people) children were starving in (insert the country of your choice). With my mother, it was always Poland. That's where her parents were born, raised and married. My mother was smart enough to make this rule easily enforceable, which meant she seldom challenged her children, food-wise. The only obstacle – served about once a month – was calf's liver, but Mom turned it into hash by grinding the liver with onions and bacon. (I was shocked years later when liver was on the menu at a college dormitory and it turned out to be a well-done hunk of meat that was tougher than rubber; shocked even more when I was told that's the way it was usually served.) Anyway, Helen Major stuck with proven favorites; finishing her meals was a pleasure, not a chore. But Mary Beth, that little rebel, always stopped a delicious morsel short. Memories of this quirk rush back on me whenever I see a certain "Everybody Loves Raymond" episode. It's the one based on Raymond Romano's recollection of his brother's habit of touching food to his chin before he eats it. The most puzzling example of my sister's ritual involved strawberry shortcake. She'd invariably leave one perfectly good strawberry and a mouth-watering dollop of whipped cream on her dessert dish. This habit annoyed us ... at first. Eventually we came to accept it as Mary's offering to the food gods. OR PERHAPS Mary left those scraps for one of her three friends to finish. Or maybe the ritual began when Mickerbock dared Mary to challenge her mother. That would be such a Mickerbock thing to do. Clearly, it wasn't Mickerbeek's idea. She would have advised Mary Beth to obey her mother. Shiny, on the other hand, would have instructed Mary to hurl her plate across the kitchen. Bad seed, that Shiny. More than 50 years have passed ... and Mary continues to leave not scraps, but a few perfectly delicious pieces of food on her plate. I'd like to blame this on the invisible Majors, but they disappeared about the time Mary Beth started school. I suppose it was good for Mary that she outgrew this phase (which, in memory, seems a lot longer than it really was), but I, for one, missed having them around. Better a story about imaginary friends than the later displays of Mary Beth's teenage angst. Alas, Mickerbeek and Mickerbock never talked to Mary Beth again. Fortunately, neither did Shiny. |

|

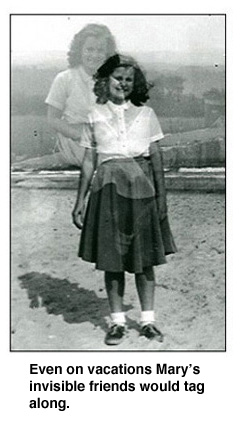

| – JACK MAJOR | |

| The day Mary met Richard Chamberlain | |

|

|

She grew up in Solvay, NY before marrying Fred, they eventually settled in the community of Westvale. After both of their mothers' passed, Mary and Fred followed their daughter Danielle to Naples, in 1998. Mary is survived by her husband, Fred; her brother, Jack (& Olinda) Major and his family; her son, Brian and his family; her daughter, Danielle, and her Smolinski cousins and family; as well as Kenga, the last in a long line of dogs that Mary doted on. Arrangements were under the direction of Gendron Funeral & Cremation Services Inc., located at 866 99th Avenue N, Naples, FL 34108. 239-596-5288 www.gendronfuneralhome.com Published in the Syracuse Post Standard from Aug. 28 to Aug. 30, 2018 |

|

| HOME | CONTACT |

As things turned out, Mary Beth didn't see our father, but she had the good sense to return on her own. I had followed her and was impressed that she went almost all the way to the bus stop. I can't remember what her issue was; my parents were like Ozzie and Harriet. You had to be in an unusually pissy mood to be upset with them. Then, again, she could easily have been mad at me; I wasn't the terrific big brother then that I am today.

As things turned out, Mary Beth didn't see our father, but she had the good sense to return on her own. I had followed her and was impressed that she went almost all the way to the bus stop. I can't remember what her issue was; my parents were like Ozzie and Harriet. You had to be in an unusually pissy mood to be upset with them. Then, again, she could easily have been mad at me; I wasn't the terrific big brother then that I am today.

Mary Major Chard passes away

Mary Major Chard passes away