| HOME |

|

|

|

A lot has changed along the Lake Ontario shore since I wrote the following piece, and most of that change has not been good. North Sandy Pond and the strip of sand that stands between that pond and the smallest of the Great Lakes is the subject of my piece, and the site of many wonderful memories. I haven't visited Sandy Pond in many years, but I have read a lot and seen dozens of photos and videos which indicate that the homes, cottages and businesses in this area are in trouble, thanks to the record high level of the water in Lake Ontario, responsible for flooding all along the shore. Sand dunes are being washed away, docks and buildings were under water this spring and early summer (2019), and what so far is incredibly sad threatens to become permanently tragic, not only for the people who live and vacation there, but also for the many thousands of creatures that find their habitat under attack. |

|

|

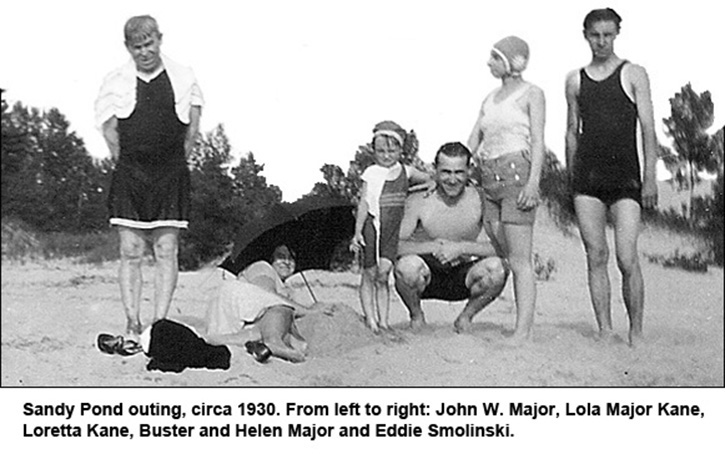

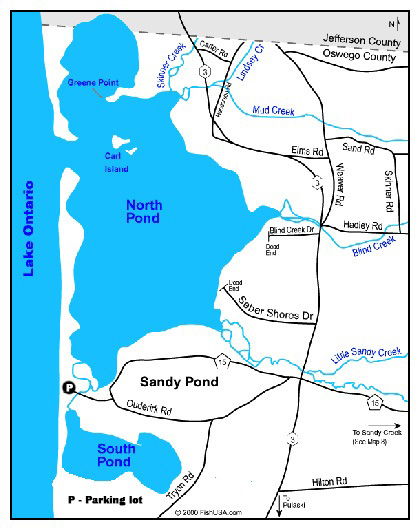

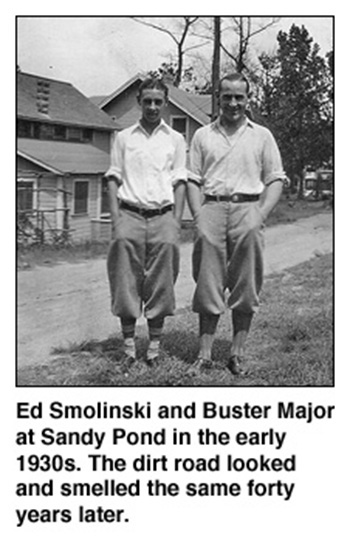

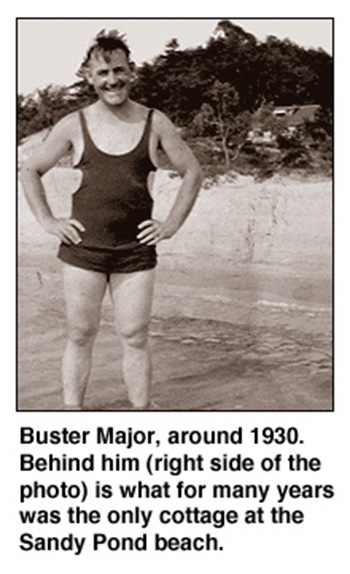

Sandy Pond sits atop my list of favorite vacation places. To locate Sandy Pond, you need a map of New York. Run a finger along the eastern shore of Lake Ontario. About 40 miles south of the St. Lawrence River you’ll come to a skinny peninsula that separates the Great Lake from a pale blue blot to the east. Welcome to Sandy Pond. Your map may show two blots – North Pond (or Big Sandy) and the much smaller South Pond – connected by an umbilical-shaped stream. Combined, they are known as Sandy Pond, more than four miles long and two miles wide. A channel splits the peninsula and connects North Pond with Lake Ontario. I believe the first channel was dug by New York State in the late 1890s, but like Until fairly recently, boats on Sandy Pond were relatively small, but today's cottage owners could – theoretically – cast off from their docks in larger craft and sail around the world. More likely they visit the Thousand Islands to the north or fish the mouth of the Oswego River to the south. A familiar problem for boaters is the annual uncertainty of the channel depth. Both North and South Ponds are rimmed by vacation cottages, trailers and a few year-round homes. There are a couple of small marinas and, I think, only one restaurant located along the shore of North Pond. There's nothing fancy here. What you pay for a month’s vacation might get you a week in, say, Hilton Head. Sandy Pond is decidedly blue collar. It's also well-loved. MY FAMILY'S love affair with Sandy Pond began in the 1920s. The couple who would become my parents, Buster Major and Helen Smolinski, lived in Solvay, a Syracuse suburb about an hour’s drive from several fine Lake Ontario beaches, including Fair Haven and Selkirk Shores, two popular state parks. However, my father had heard about a gorgeous spot near the village of Pulaski. (And in New York, unlike other states that honor Polish patriot Casimir Pulaski, the last syllable is pronounced "sky," not "skee.") It's possible my father might have been directed to Sandy Pond by his sister Lola's husband, Tony Kane, who during Prohibition used his boat to deliver booze from Canada to the United States. Kane knew the lake well, so he probably had visited the Sandy Pond area. (Unfortunately, he pushed his luck too far when he and his associates attempted to cross the lake in December 1930. They encountered a fierce winter storm which sank their boat. Kane and his partners drowned.) In any event, my parents-to-be, along with family and friends, began visiting Sandy Pond in the late 1920s and were not disappointed. I suspect they felt like 15th century explorers discovering a new land. Sandy Pond gave you that feeling. It would for many years. I recently discovered that in the early 1900s some people believed Sandy Pond would become a popular summer resort. All that was needed was a dependable channel ... which was never constructed. By my first visit, in the mid 1940s, there was nothing to indicate any effort had ever been made to develop the area. Oh, there once had been a well-known hotel and restaurant near the channel, but it closed before I was born. Most of the Pond's summer residents used the so-called Boaters' Beach, also near the channel. My parents went to a beach three miles south and a world away from the channel. This beach wasn't all that accessible and was little used (as you can tell from the photo above.) That changed in the 1950s. It might have been the worst thing that ever happened to Sandy Pond. I sense some confusion. Am I talking about a pond or a Great Lake? Why say Sandy Pond if I mean a beach on Lake Ontario? Habit, I’m afraid. Old-time Pond people tend to refer to the whole area as Sandy Pond. You do not swim in the pond. I’ve seen people try, but they’re probably still pulling seaweed off their legs. I suspect North and South Sandy Ponds were named not for a sandy bottom, which extends only so far, but for the long, narrow and steep sandhill that separates the ponds from Lake Ontario. THERE ARE spots near the channel where a pond swim isn’t a bad idea, but as of my last visit – granted, that was 25 years ago – the pond was polluted and thick with weeds, the sand bottom buried beneath layers of muck. Back then it was necessary for an association of property owners to bring in a huge, riverboat-like thrasher every summer to run a Zamboni-like pattern through the pond, temporarily clearing paths for the assorted motorized watercraft turned loose each summer. In those days cottages disposed waste into the pond. That is no longer the case. The resulting change in the water chemistry apparently has the weeds under control, so the thrasher is no longer needed. (Note: The pond also is popular during the long, cold Northern New York winters when the water freezes to a thickness that allows ice fishermen to drive to their favorite spots.) WHEN I MENTION the beach at Sandy Pond I'm referring to the three-mile strip of sand south of the channel on the Lake Ontario side. Many people unfamiliar with the Great Lakes don't realize how closely their beaches resemble those you'll find on oceans. For one thing, there often are huge waves. You can't actually surf in the Great Lakes, though many have tried. But these five, huge bodies of water are unlike other lakes. Their beaches are among the world's most beautiful AND most interesting. Until the 1950s, that strip of sand between Sandy Pond and Lake Ontario could have been a site for TV's "Survivor." First off, the road to the beach – Oswego County Route 15 – didn’t actually go to the beach. From where the road ended, there was no beach in sight, only sand dunes beyond a small, rickety bridge that spanned the narrow channel that connected North and South Ponds. When the lake was rough you could hear surf, but you didn’t know exactly where it was. There was no parking lot; cars were left on the skinny road’s uncertain shoulders. The walk – half a mile or much longer, depending on where you parked – was unpleasant exercise on hot, superfine sand that collapsed under foot and filled your shoes. (Yes, you've been to a beach, so you know the feeling, but Sandy Pond was a special test of patience and leg muscles. The difference between its sand and, say, what you'll find along the Atlantic Ocean, is like the difference between Splenda and regular, granulated sugar. Lake Ontario sand is superfine. Dig into it and you won't encouter creepy, crawly critters. Only sand and occasional rocks.) NO CONCESSION stand awaited Sandy Pond visitors in the 1920s, no toilet facilities, no trash barrels. What was needed for a day at the beach had to be carried in – and out. People were responsible for their garbage. Maybe that's why people stayed away. (Many who came in the 1950s and '60s, when easy access was provided, turned out to be lazy and inconsiderate slobs. More on that later.) In the meantime there was an endless, nearly deserted stretch of white sand and driftwood between white-capped blue-green water and tree-shaded dunes and 150-foot high sandhills that promised a thousand hiding places. In short, Sandy Pond was paradise. |

|

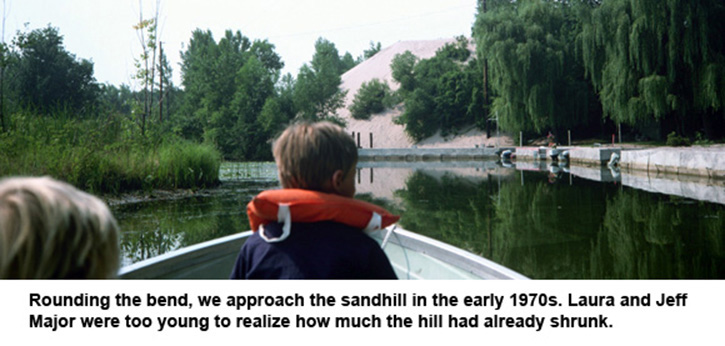

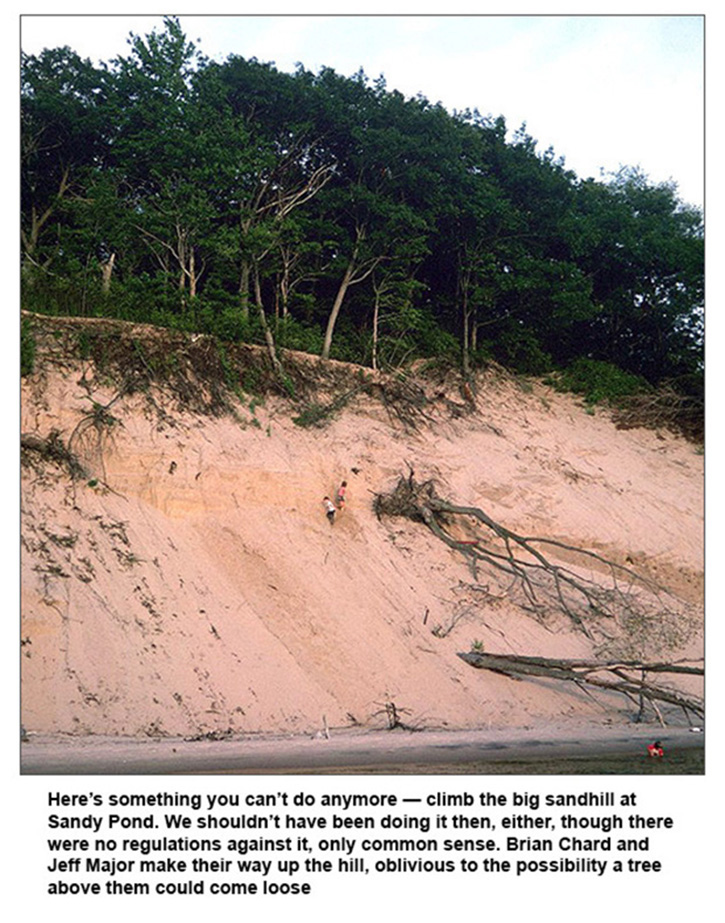

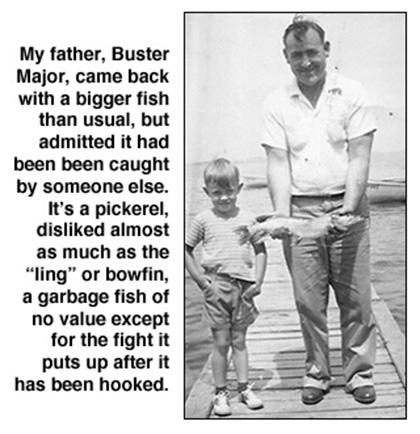

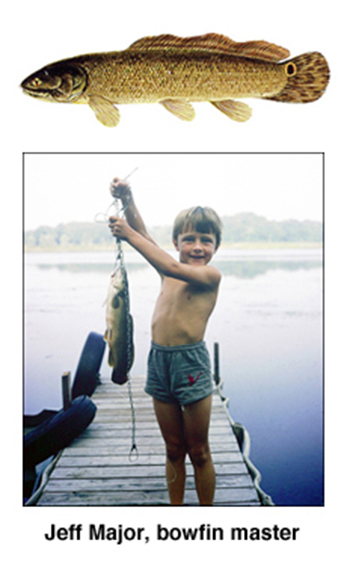

For many years the most popular spot on the beach was an open-faced sandhill that overlooked North Pond. It was relatively free of vegetation, a large, inviting patch of light brown that drew eyes from every cottage on the pond. It marked my family's favorite entrance to our summer amusement park. From the top of that hill was a terrific view of the main attraction – Lake Ontario, about 150 yards away, past the valley of sand. In the middle of that valley, as though by design, was a long, sun-bleached stalk of a fallen tree. (By the time the photo (above, right) was taken many years later, the scene had changed considerably.) To the north of the valley were even higher sandhills thick with birch trees and various bushes that had somehow taken root, at least on the pond side. To the south were several tree-shaded mini-dunes, perfect for people like me who needed refuge from the sun. Years later, when the hordes invaded, I pictured them having to funnel past a beach maitre d’. (“Party of six? Sorry, all of our private dunes were booked weeks ago. You really should have made a reservation.”) IN THE 1930s, my parents, aunts and uncles began renting two cottages for two weeks every summer. They were joined by my grandmother, friends and other relatives. Their cottages were directly across the pond from our favorite sandhill. Sandy Pond’s middle may be more than two miles wide, but it narrows considerably at the cattail-clogged southern end. It was along those cattails that my Uncle Bill and his friends would station themselves during the fall duck-hunting season. By the 1940s our family had as many children as adults. The two cottages were overcrowded, but the good times continued. An uncle would often take my three older cousins and me to the beach by boat, sometimes rowing, sometimes putt-putt powered by a small outboard that only slightly shortened the trip to the sandhill, a trip that fed my imagination. The east side of the pond was mostly open water, but the west side belonged to the cattails. Tucked in among the trees at the base of the tallest sandhill on the west shore were two cottages. Thousands of cattails had to be cleared out so that boats could reach those cottages, as well as a bait shop at the southern tip of North Sandy Pond, the canal-like stream to South Pond, and, of course, THE sandhill. For me, the boat ride through that opening in the cattails was like a visit to a Georgia swamp. We skimmed over weeds and waterlilies, our view limited to the sky overhead and the cattails close on both sides. Around the bend, approaching two shanty-like cottages, it was easy to picture unsmiling men in coveralls and floppy hats, eying us suspiciously, rifles in hand. (Years later my imagination would add the soundtrack from "Deliverance.") It’s true, you know. Kids had just as much fun before Walt Disney packaged and merchandised it. That ride to the sandhill was as enjoyable as Pirates of the Caribbean. North Sandy Pond and the much smaller South Sandy Pond are separated from Lake Ontario by a hill of sand that was – and may still be – about 150 feet high along much of North Sandy Pond's west shore. However, there was only one spot where the white sand really stood out on the pond side of the hill. Vegetation camouflaged the rest of the hill where most of the trees and plants were sheltered from the wind and water that played havoc on the side that faced the lake. (It didn't occur to us, as children, that the trees on the lake side of the hill were being slowly destroyed, one row at a time.) That bright spot of sand near the southern end of North Sandy Pond was a beacon that summoned us to the beach. It stood tallest in the late 1940s when it wore a crown of vegetation, including poison oak, though that didn't discourage us from climbing the hill and charging down the other side to the water. Why most of this particular hill was free of vegetation wasn't a question that interested us. Obviously, it should have. We didn't have access to a boat that was practical for trips to the beach by the channel, but that was okay with us because at the time we preferred the other beach, which soon would be drastically changed. Anyway, it was a short boat ride to our preferred beach. It also was more fun, at least for kids, to enter the beach off a boat at the Sandhill where we'd imagine we were Marines. We jumped from the boat and scurried up the hill, and crawl past the poison oak to the clearing at the top of the hill. There we’d lie low and scan the area for the invisible enemy, then rise and charge at full speed, leaping over or diving under the horizontal tree stalk, then running ‘til we were knee deep in Lake Ontario. (Each year we'd sustain two casualties – my cousins Bobby and Bimby Smolinski – the only ones susceptible to the poison oak. The reaction sometimes was severe enough to earn them an early trip back to Solvay.) WOMEN in our family preferred going to the beach in fully loaded cars. My family – especially my mother and grandmother – didn’t grasp the picnic concept; they preferred seven-course dinners served over sand. (Once I tripped and fell while carrying a chocolate cake. I landed on my elbows, trying to maintain that all-important separation of frosting and sand, a mission impossible. Most of the cake was saved, but for years I heard about that accident and how I'd gotten sand on the frosting.) Things were slow to change after my parents’ first visit. Twenty years later it was still a long walk to the beach. There was some fun in pretending we were wandering the desert, looking for an oasis, but we’d have enjoyed it more if we weren’t hauling supplies for a small army of soldiers with huge appetites. Sand-coated food and all, each trip was worth the effort. We were deeply in love with Sandy Pond and regarded the beach as our private playground. I'm sure anyone who ever went there in the 1920s, '30s and '40s felt the same way. When the 1950s arrived we began noticing changes on the hill, but didn't grasp the implications. For one thing, the poison oak disappeared. Sandy spaces between plants were wider. We thought that was a good sign. We were wrong, of course. THE BEACH was only part of a Sandy Pond vacation, often a small part, thanks to the erratic Northern New York weather. The temperature would hit 85 degrees one day, only 55 the next. The sun might disappear for half-a-week, hiding above soot-covered, drizzle-oozing clouds. Even a sunny afternoon might be rudely interrupted by a sudden thunderstorm that seemed to race across the lake. Well, better the afternoon than late at night when the lightning seemed unusually menacing, the thunder deafening. Standing near and hovering over us were tall, inviting targets, elms and oaks. The cottages were about as protective as cardboard boxes. But like a good ghost story, the storms were more thrilling than scary. Such as the night we got caught in one on our way back to the cottage from Pulaski where my parents and I had gone to a movie. It’s a seven-mile drive on a hilly, rural road that I call the Pulaski-to-Sandy Pond Roller Coaster. It’s pitch black even on a good night; through the rain pellets that night, visibility was about six inches, but off to the right, shimmering through our windshield, were lights. There weren’t many houses along this road; that had to be one of them. My father managed to find the driveway, and seconds after we pulled in, a farmer looked out his front door and waved for us to drive up alongside the porch. We did, and when my father explained our presence – which the farmer had already guessed – we were invited inside. About fifteen minutes later the storm passed, the sky cleared, and we set out to complete our drive back to the cottage, half expecting it had been swept into the pond. But it had stood tall in surviving another Sandy Pond storm. Which wouldn't be true at few years later for at least one cottage that someone decided to build on the sandhill overlooking the lake. For kids, at least, a Sandy Pond vacation was an escape from the world. It was a stress-relieving tradition I continued through adulthood. No TV, radio, telephone WE SPENT as much time fishing the pond as we did swimming the lake. Not that we caught anything worth mentioning. For us, the fun of fishing was in the expectation, not the result. (Truth or rationalization? You decide.) Only rarely did I fish with my father because he liked staying out for hours. I didn’t have the patience. I preferred fishing from the dock. Either way, my catch was the same – divided evenly between sunfish and perch, some of them minnow-sized. Sometimes I caught bullheads – the small cousin of the catfish. That meant it was time to quit for the day. The bullheads took over in the late afternoon. Occasionally someone would secure a pole to the dock, letting a baited hook dangle overnight. Sometimes we'd find a fish on the end of the line the next morning. It was always a bullhead. Sunfish and perch were what my father caught, too; it’s all he wanted to catch. He kept the sunfish and released most of the perch, keeping only those few that were at least 10 inches long. My father fished until he had at least three dozen sunfish he pronounced large enough for eating. Upon his return to the cottage, he’d scale and clean them and my mother would fry them for supper. Sunfish are good-tasting, but small, and my father didn’t fillet them, which guaranteed he’d be the only one eating them. For the rest of us it wasn’t worth the effort to separate tiny bones from the meat. (Years later, when I discovered the flavor of perch, I reversed my father’s pattern. I kept only perch and released all sunfish.) ANOTHER RITUAL: In preparation for vacation, my father would soak our back lawn the day before we left. That night he and I would go out with flashlights and catch nightcrawlers that had been flooded out of their holes. We’d stay outside until we had at least 100 worms. My father would pack ‘em up in a way that insured he had live bait for at least the first week. Years later my brother-in-law Fred would do the same thing, but on an even larger scale. He was a more determined fisherman than my father, with better results. He caught a few smallmouth bass. He and my son Jeff each would have fun catching a fish I never saw when I was a kid, a fish that was good for nothing but the momentary thrill it provided during its fierce struggle to be free of the hook. But I'm getting ahead of myself. |

|

We traveled to Sandy Pond not by car, but by time machine – set for 1930. There was indoor plumbing, but you couldn’t drink the tap water. We fetched it across the street, pumping it from a shared well, something I enjoyed doing –at least, for two weeks. Many years later my kids did the same, but only for the novelty. I had long since given up drinking from the well. When we left for the pond, we’d take a two-week supply of drinking water with us. The first few times I went to Sandy Pond, starting in the mid-1940s, we kept our perishable food in an icebox. Going with my father to buy 25-pound chunks of ice became another vacation adventure, though for my parents it was merely a reminder of their childhoods and a reason to be grateful for the refrigerator they had at home. Also impervious to change was the neaby village of Pulaski, which could have been a living history museum or a set for a remake of "Bonnie & Clyde." I noticed little difference in Pulaski from the time I was a child until the time my own children were teenagers. (A Providence Journal co-worker whose job as the newspaper's outdoor writer occasionally had him covering fishing on the Salmon River, which runs through Pulaski, said the area put him in mind of the Old West. Oh, people got around in trucks, not on horses, but, he said, "every truck there has a gun rack.") EACH YEAR our extended family of uncles, aunts, cousins and the grandmother we called Nana returned to the same two Sandy Pond cottages. My parents, my younger sister and I stayed in the smaller cottage. It could sleep six, so we were joined by Nana and one of my cousins.

Both cottages were built on the side of the 20-foot slope from the road to the pond, but the smaller cottage, which also had an upstairs, was grounded at pond level; the larger cottage was two flights of stairs above the water. When the pond was roiled, the waves would lap against the small cottage. You’d look out the kitchen window and think you were on a boat. Look out that window too long and you could get sea sick. Most of the cottages, as well as a small hotel, general store and a small marina, were lined up along a dirt road that intersected with County Highway 15 about 50 feet north of our cottages. That road went north by northeast, parallel to and a lot’s length from the pond shoreline. Over time the dirt turned black under the oil that was used to seal and maintain the road. The mixture of oil and dirt produced a pungent odor that could be bottled as The Scent of Sandy Pond. A perfect gift for Pondaholics – and stock car race drivers. Sure to evoke fond memories. Among mine: Walking along that road to and from the general store to play Ski-ball, five cents a game. I’d leave the cottage with a pocketful of nickels and return an hour or so later to ask my mother for more. A few years later the ski-ball game disappeared. So did the store. The odor, however, will linger until the dinosaurs return. |

|

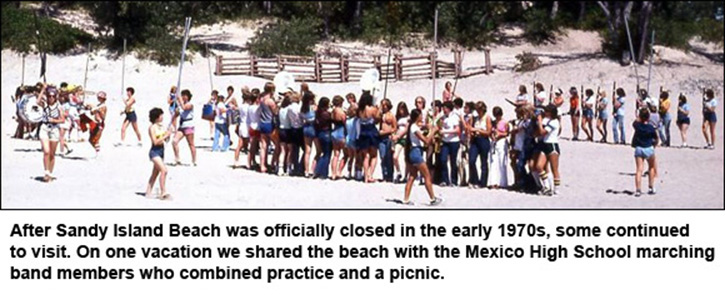

At Sandy Pond, the 1950s began with a jolt. No longer was the beach a destination for those who just "vanted to be alone." A retired businessman from Syracuse had purchased the beach. LeGrande Smith was his name. Smith and his wife, Eva, built a dirt road from the small bridge to a beachside parking lot and charged admission, Mrs. Smith collecting. My mother didn't like the woman's grin. "It's evil," she said. We joked that she probably lived under the bridge and we labeled the entrance fee “a troll’s toll.” My mother entertained the idea of a boycott. But resistance was useless. Times had changed. OVERNIGHT, the previously unnamed beach at Sandy Pond became known as Sandy Island Beach. There were lifeguards – and a loose set of rules. Instantly it became THE place to go. On weekends, the parking lot was jammed with cars from Syracuse and Oswego. Another parking lot opened, closer to the bridge, at the base of a tall sand dune. It quickly filled. Down the road, yet another parking lot opened. Still not enough space to handle the swimmers-come-lately. Many were forced to abandon their cars along the road, like the good old days. The walk to the beach might be longer than ever, but not as difficult, thanks to the dirt road that had replaced the shifting-sand trail. It didn’t matter how inconvenient it was for some. They HAD to go to Sandy Island Beach – especially if they were teenagers. A season or two later the parking lot by the beach had company – a restaurant, restrooms and a small motel. In the process the beach became an obstacle course, impossible to walk without stepping on people or into food. The BUT PARADISE wasn’t lost. It had moved – about a mile up the beach. There you could be alone at the base of a sandhill, no lifeguards and no rules. The further north you walked, the wider – and lonelier – the beach became. Occasionally you were confronted by people who owned camps on the pond side of the sandhill. They believed the stretch of sand at the base of the hill below whatever path they had taken to get from their cottage to the lake was their private beach. It wasn't of course, though I could understand their annoyance. For those who had parked at the beach and were trying to escape the crowd it was a small matter to move on another 50 yards or so and give the camp owners their space. Away from the congestion there was plenty of beach to go around. Even here, however, change was brewing. For years, there had been a single cottage on the lake side of sandhill. For the relative few who visited the beach in the old days, that cottage was a curiosity, not an inspiration. But now Sandy Pond was attracting thousands. Some of them were bound to think a sandhill-based cottage was a mighty fine idea – and maybe it was ... at the time. Sandy Island Beach remained wildly popular for several years. My mother quickly got over her hurt; she and my father continued to vacation at Sandy Pond. In 1953 it became more than ever my summer home away from home; my friends now included licensed drivers. In 1954 I got my license. My friends and I would go to the beach every weekend, with dates or without. It was high school heaven, fondly mentioned two years later by many who signed my senior yearbook. Students in several Syracuse-area schools felt the same way. There apparently was a Senior Day tradition at Liverpool High to skip school and go to Sandy Pond. My parents’ streak of consecutive years at Sandy Pond ended in 1961 when my visit was limited to a weekend leave from Camp Kilmer, N.J., where I was stationed during my six months active duty. By the next summer I’d be a feature writer at the Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal. Nine more years would pass before I saw Sandy Pond again. It wouldn’t be a pretty sight. An email from Stephen Kappesser explained what happened. Kappesser, now a resident of Joppa, Maryland, grew up at Sandy Pond.

IT'S 1971 . . . I am living in Rhode Island with my first wife and our two young children. During a July visit to my parents’ home in Solvay, I’m overtaken by an irresistible impulse – I drive my family to Sandy Pond. I had been told of the fire, but was given no details. Besides, It’s a perfect beach day. So I remain optimistic – until we arrive. Around the parking lot is a Sandy Pond Stonehenge – blackened ruins of a burned-out building. The smell of charcoal is everywhere. Beyond, the once-beautiful, white sand beach, is a sea of broken glass, cans and pools of trash around rusting trash barrels. I make a brief inspection, we leave, and all the way back to Solvay I bounce an apology off my wife’s “Yeah, right!” expression, then babble on about once upon a time. A YEAR LATER, my sister, God bless her, manages to go me one better. She talks my parents into returning to the big cottage for two weeks in August. She’s married and the mother of three-year-old Brian, who makes his Sandy Operating out of the cottage is an immediate plus. My kids have their first fishing experience. It’s fun, because every fish excites them, no matter how small. It’s sunny and hot, making the beach a good idea, regardless of its condition. We go with fingers crossed. Pleasant surprise. Sandy Island Beach isn’t dead, after all. You still can’t walk barefoot through the soft sand, but a lot of cleaning has been done by volunteers, many of them local high school students. These people become the unsung heroes of Sandy Pond. However, the land remains unsold; I have no idea whether we are there legally. Frankly, I don’t care. My son and I go for a long walk; the upper beach is as clean as ever. We also visit my favorite sandhill; it looks even better than ever. The poison oak that sent two of my cousins home has disappeared. The hill is pure sand. But looks are deceiving. The lack of vegetation is a bad thing, a reason the hill would virtually disappear over the next 20 years. However, my son is impressed. For sure, he’s hooked on Sandy Pond. |

|

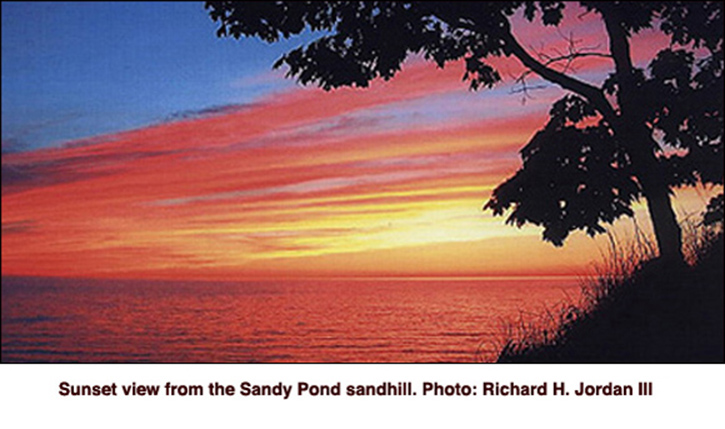

THE GREAT LAKES don't get the respect they deserve. Too many folks don't know anything about them ... like a former Providence Journal co-worker who, when he went to Chicago for the first time, expected to look out at Lake Michigan and see what was on the other side. But the Great Lakes are like oceans. Stand on top of a sandhill at Sandy Pond and look due west. Buffalo and Toronto are out there somewhere, but all you’ll see is water. Lake Ontario is 193 miles long. Also, it’s seldom flat. There are waves that range from tiny to watch-out-for-the-undertow. I like a rough lake, with waves in the 3-to-6 foot range; my sister prefers it calm. During the course of any two-week vacation we’d both be satisfied. Which reminds me of my father’s favorite Sandy Pond warning: “Be careful! Last year I saw a bunch of people get sucked away. They found ‘em a few days later in Toronto!” A complete lie, but one that worked because the undertow at Lake Ontario is often dangerous. I've encountered stronger undertow at Atlantic Ocean beaches, but it doesn't take much of a storm to whip Lake Ontario into a frenzy. As mentioned earlier, it would be foolish to take a surfboard to Sandy Pond, even though the waves are often inviting. However, the body surfing is terrific. The waves break far from shore, then rise and break again several times over a series of sand bars. For my money, the Great Lakes enjoy two big advantages over oceans: (1) freshwater is a lot more refreshing than salt, and (2) the sand is . . . well, simply sand, screened and sifted by Mother Nature. Dig deep into Lake Ontario sand and you'll feel like a kid again, playing in a sandbox. Finally, from the eastern shore of Lake Ontario are the best sunsets in the world. Sunsets that will break your heart. Trust me. You cannot top them. UNLESS YOU own a cottage, there are downsides to a Sandy Pond vacation. It’s not easy to get a line on a good rental. You have to know somebody who knows somebody. That’s how we sometimes had to operate. The one year I took a classified ad at face value we wound up in the cottage from hell. What made the disaster complete was another downside – Lake Ontario-influenced weather, always an uncertainty. I’ve mentioned this before, but it bears repeating. It may well rain as many days as not, so you'd better have a dry, comfortable cottage. In such a cottage, a rainy day can be rewarding – if you've packed games and books. Some years I'd do more reading during our Sandy Pond vacation than I'd do for the next 50 weeks. Also be warned that Lake Ontario is considered the most polluted of the five Great Lakes. That’s right, Lake Erie no longer holds the title. The pollution isn’t visible; Lake Ontario still has its good looks. And to my knowledge, the stretch along the eastern shore, which includes Sandy Pond, has always been considered safe for swimming. However, were my father still alive and fishing, he’d think twice about eating those sunfish. One obnoxious Great Lakes beach problem has been addressed since my first years vacationing at Sandy Pond. That problem: alewives, a species of sardine-like fish that 50 years ago became much, much too plentiful for its food supply. Zillions would starve and die each year during the early weeks of summer. The bodies piled up on the beaches, leaving an unsightly mess and a stench that would gag a pig. (The worst cases were along the shore of Lake Michigan near Chicago where it could have – but didn’t – inspire a Dr. Seuss book, "Seven Inches of Alewives.") Much has changed in the past 30 years. Pacific salmon, imported to feed on alewives and attract fishermen, finally have had an impact. Scientists also successfully attacked the lamprey (an eel), a notorious killer of lake trout and other fish. Trout were re-introduced and are thriving, thanks in part to a diet Even during those bad years there was a way to avoid the unpleasantness, at least at Sandy Pond: delay the vacation until August, by which time the fish bodies and the stench miraculously disappeared. Unfortunately, the first Mrs. Major was introduced to Sandy Pond in July. THE KIDS and I returned to Sandy Pond in 1976, and a year later we were joined by the second Mrs. Major. Through my cousin Loretta, whom I hadn’t seen in years, we met a family who owned a trailer on Green Point, a peninsula that juts into the pond three miles north of the cottages our family used to rent. The trailer was lovely, but our timing was terrible. North Pond, storm-battered for three winters, was angry. Its channel was wide and wild, a long stretch of the sand barrier was underwater, allowing the lake to crash the pond. The only boats for rent at Green Point Marina were small, flat-bottomed things, shaped like oversized banana-split tubs. We rented one and attached a 5-1/2-horse outboard motor borrowed from an uncle. We could have made better time with an eggbeater. Because of the lake's influence, the pond was unusually rough. Going to the beach in our rented boat was like sailing the ocean in a Tupperware bowl. I think we completed the trip once. Other days we either turned back or made the trip by car, which defeated a main purpose of our new location. The fishing was disappointing, even nasty. Just when we were convinced there was no point continuing, we’d get a message from the pond that said, “It’s your fault, you know. You’d be catching a ton if you weren’t so inept.” Like the time we anchored in sheltered water east of tiny Carl Island, off Green Point, where we quickly caught three of the biggest yellow perch I’d ever seen. More, we said. Replied the pond: Only if you display a little skill and something more than nightcrawlers dangling from a hook. Result: Not even a nibble for the rest of the day. Later in the week my son Jeff stared down at the water from the pier where our boat was tied. Suddenly there it was, a fish this long (hold your arms three-feet apart). He ran to the cottage to get his pole. You could hear the pond laugh. The next year, when we returned to the south end of North Sandy, across the street from the “big” cottage, my wife Linda made an excellent suggestion. We rented a canoe, with which we explored the pond in ways I’d never done before, especially through that area I referred to as the Georgia swamp. Jeff spotted some turtles and decided he'd net one. He tried and failed several times. Then Linda tried – and a competition was underway. Finally Jeff came up with a painted turtle in our small fishing net – obscured by five pounds of seaweed. Oh, yes, and an empty Budweiser can. While Linda was flailing away with the net during the turtle hunt she came upon a large fish apparently stymied by a cattail maze. The fish, of course, found a path to freedom. Anyway, once again we had our hopes raised that if we fished this spot we'd finally catch The Big One. Finally, we did. More accurately, my son Jeff and my brother-in-law did. Bowfins are a much-despised garbage fish. They eat almost anything and thrive where other species curl up and die. Compared with other Pond fish, bowfins are huge (up to two-feet in length), but big-boned and reportedly taste like something you wouldn't even serve your worst enemy. But all that mattered to Fred and Jeff was the size, 2-to-4 pounds. They felt much larger because bowfins are fierce fighters, and on that basis are well-worth the effort involved in making the catch. At least, that’s what Jeff tells me. I never had the chance to find out. Jeff, meanwhile, became our bowfin master, catching at least one during every vacation thereafter. BY THE WAY, ling is only one of the bowfin's aliases. Among the others: mudfish, dogfish, grindle and spottail grindle. Perhaps because of its reputation – and I'm not making this up – it’s also called . . . a lawyer. Bowfins are easy to identify. The clue is one of its aliases – spottail grindle. There is a prominent black spot on every bowfin, just in front of its rounded tail; on males that spot is rimmed in bright orange. (This is not to be confused with the red drum – aka channel bass or redfish – a coastal fish that also has a large black spot at the base of its tail.) A few years after our first encounter, I saw a bowfin in a 10-gallon tank at the home of a family I was visiting. There was no mistaking it. That rounded tail is almost as distinctive as the spot. The people told me they bought it at a New England pet store where the owner – perhaps innocently – told them it was a rare Japanese fish. |

|

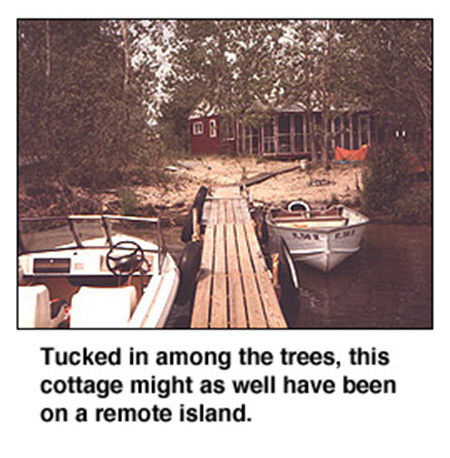

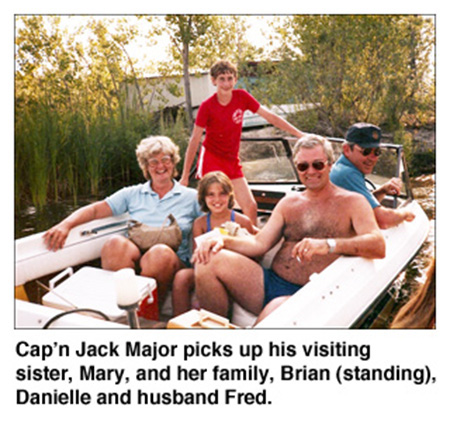

My sister and I and cousin Loretta weren’t the only family members who hadn’t abandoned Sandy Pond. Sandra, the cousin who, as a child, used to bunk with my sister in the small cottage, still loved the place. Well, why not? She and her husband, Paul Grecco, had found a secluded cottage, accessible only by boat. The cottage also was fairly new. It had to be because it was located on the west shore of the pond along a treed strip I’m sure didn’t exist in the 1940s. When I was a kid, the word “fragile” wasn’t in my vocabulary. Even after it was, I didn’t apply it to a piece of land, a hill of sand or a body of water. Back in the ‘50s we thought most things would last forever. Short of nuclear war, that is. But that’s a whole other story. Step back one decade. We’re in the small cottage during one of those memorable Lake Ontario storms. The rain stops, but wind still howls. We look north, way up the pond where the last sandhill falls to earth, leveling off about three feet above lake level. From there to the channel is a gently arched mound of sand, probably 200 feet wide, almost a mile long. That's where it is happening – Lake Ontario waves so high they are crashing over the sandstrip, into the pond. We’re entertained, even amused in a wow! look at that! sort of way. We're like people who stand on the Atlantic Ocean shore to watch waves during a hurricane. The storm’s implications don’t register. The sand strip is Mother Nature’s Play-Doh, constantly re-shaped by the awesome combination of wind and water. AHEAD TO 1974: A cover story in the Syracuse Herald-American’s Empire magazine tells of problems Sandy Pond property owners have encountered due to the rising lake. The cover photo is a man standing at the end of a short rock wall he built in a failed attempt to keep the lake from swallowing an estimated 80 percent of his property. Property along the sand strip. I had sympathy for those who owned cottages on the east shore of the pond, two miles away. Some were old, established cottages on lots that had never before been attacked by water. I could understand their anguish as inch by inch their property disappeared. But that man on the rock, what was he thinking when he bought 100 feet of sand? And the man who sold it, should I see him about buying a lowcountry swamp for my Carolina dream house? So I felt nothing for the man on the rock. He should have known better. So should the people who built cottages on the dunes north of Sandy Island Beach. Especially the people whose cottage eventually went sand-skiing down the hill. By the end of the ‘70s, the lake receded; the sandstrip (or split, as locals call it) re-appeared and Sandy Pond displayed the results of its latest makeover. The Empire magazine article had – without explanation – illustrated the process in two striking photographs. One, taken in 1936, showed a bare sand mound where, 10 years later, the waves overflowed while we watched from the small cottage. In a 1974 photo, that mound is much higher, wider and thick with trees. It’s where someone built the cottage my cousin Sandra and her husband rented in the late ‘70s. The cottage was tucked in among those trees, birches and pines about 20 feet tall. To vacation in that cottage you need a boat. Or a hitch in the French Foreign Legion ... because there are miles of sand between that cottage and civilization. A friend lent cousin Sandra and her husband a boat. I envied them. The cottage was clean and comfortable, its kitchen well-applianced. It was too far from the nearest powerline, so the cottage's electricity came from an oil-fueled generator. No problem. Best of all, the cottage provided easy access to the two attractions that made Sandy Pond so At first glance I knew that cottage was where we’d have our perfect vacation. But first we had to have our all-time, rock-bottom worst. That came in 1981 as a result of a last-minute decision. We had skipped the previous summer because our daughter Meridith arrived in August. We hemmed and hawed for weeks about that 1981 vacation, then made arrangements to share a Sandy Pond cottage with my sister and her family. Summer was underway. Was a cottage available for the two weeks we wanted? That it was available for every week through Labor Day should have told me something. Saying “We’ll take it!” is maybe number three on my all-time list of incredibly stupid mistakes. The place smelled of urine, every surface was sticky and your sneakers went THWUP! THWUP! THWUP! when you walked. We counted 10 million ants in the kitchen alone. Appropriately, it rained 10 of our 14 days. That my second marriage survived made me believe in miracles. We didn’t quit, though we did take a break in 1983. FINALLY, IN 1984, we made it happen, but not without some difficulty. Sandra and Paul Grecco chose not to go to Sandy Pond that year. They gave us the name of the owner of the perfect college, but he told us he preferred to sell, not rent. No thanks, I said. As June approached, with no buyer in sight, he had a change of heart. He and his wife would use it in July, he’d rent it out in August. We had our two weeks. This time I’d need a powerboat instead of a flat-bottomed rowboat and a tiny outboard. We’d be making several food runs that would require trips back and forth to our car that would be parked three miles away. The boat my cousin and her husband had used belonged to a friend I didn’t know. None of the Sandy Pond marinas rented powerboats, so I turned to the Yellow Pages where I found an ad for a marina on the south shore of Oneida Lake, 40 miles from the pond. To my surprise, the owner agreed to deliver a boat to Green Point Marina. I took that as a good omen. For once I was correct. Our boat rental included a towline and waterskis. None of us had experience waterskiing or handling a powerboat. I wasn't about to go out on Lake Ontario and I wasn’t sure anyone could get psyched about doing something in the pond that surely would drop them in six feet of seaweed-infested water with a mucky bottom that could suck you in like quicksand. But the kids did – psyche themselves up AND sink, always bobbing up for another try. It didn't take long for Laura to get the hang of it; I wondered why I hadn't thought of this a few years earlier.

However, I do not share that woman's feelings about Sandy Pond fishing. To the very end we had no luck, and in 1984 we went all over the pond looking for fish. Any kind of fish. The biggest we saw during our two weeks was off-limits. It was the male bullhead that patrolled our area, protecting his young. Oh, there was something larger nearby, but we never saw it, only the sad evidence of its presence. That evidence was a family of baby ducks. One day there were six, the next day there were five. Then four . . . But we hadn't gone to Sandy Pond to fish. We'd gone there for that state of mind. And we all found it, even Meridith, who, at age 4, appointed herself camp director, leading us on nature walks, hikes to the beach, to the dock to fish or for a ride in the boat, or on a search for the chipmunks we’d see from time to time. My wife found it, too, and even forgave me for our 1981 misadventure that had earned the code name, Empire of the Ants. Finally, we had it – the perfect vacation. Most remarkably, 1984 was the first time I’d ever spent two weeks at Sandy Pond without at least one gully-washing, teeth-rattling, nail-biting storm. I didn’t even feel a raindrop until the final morning while I was taking the boat back to the marina. Or perhaps it was a tear – for I sensed our Sandy Pond era had come to an end. My son was about to go off to college, my older daughter was a high school junior. There'd be other things for them to do in the summers ahead. It seemed a good time to quit. After all, you can’t improve on perfect. IN 1999 Sandy Island Beach became the property of Oswego County, which, by all reports, did a marvelous job of cleaning and combing the beach to create a 13-acre county park that opened in 2000 to great reviews. However, it soon became apparent the county did not have the financial resources to maintain the park, much less make the further improvements that were needed, such as construction of a bath house. After the 2003 summer season, it looked as though Sandy Island Beach might be closed. But on Oct. 30, 2003, the state came to the rescue. In making the announcement, New York Governor George E. Pataki said, "By opening Sandy Island Beach as a state park, we can provide increased public access to a spectacular shoreline property and expanded recreational opportunities. With this acquisition, we can continue to protect New York's magnificent outdoor heritage for generations of visitors to enjoy. We are committed to further enhancing the park and its facilities for patrons of all ages." Toward that end the state announced plans to build a $500,000 bath house and concession stand. In the meantime, Sandy Island Beach looked pretty much like it did as an Oswego County park, which is to say that anyone who hasn't visited Sandy Pond in 20 years or so might have difficulty recognizing the place. THERE'S LITTLE I can say about the state of Sandy Pond or Sandy Island Beach because my last visit — which produced the photo above — was in 2004. It was a brief and sad occasion, though I could appreciate the efforts being made to preserve what remains of a once wild and wonderful beach that was severely damaged by people who couldn't leave well enough alone and by high winds and cruel winters. Gone is the signature sandhill that stood like beacon at the southern end of the pond, luring visitors to the wide open beach that awaited on the lake side of that hill. As inviting as it was, the hill remained relatively untouched until Sandy Island Beach opened in the early 1950s. After that, traffic on the hill increased significantly, killing many of the plants. This made the hill vulnerable to lake winds that within a few years shoved tons of sand into the pond. The state took over that piece of property, dredged the pond, re-built and re-planted the hill, but this man-made hill is a small version of what attracted visitors 30 years ago. Also gone is the valley that ran between the dunes from the top of the sandhill to the beach. That valley has been filled in with sand and protective vegetation. This change, necessary to preserve a barrier between the lake and the pond, has greatly reduced the size of the beach. There is a walkway along the eastern edge of the beach where visitors can view the various plants placed there by the state and by Sandy Pond Association members determined to conserve the area. However, visitors are not allowed to stroll the dunes. |

|

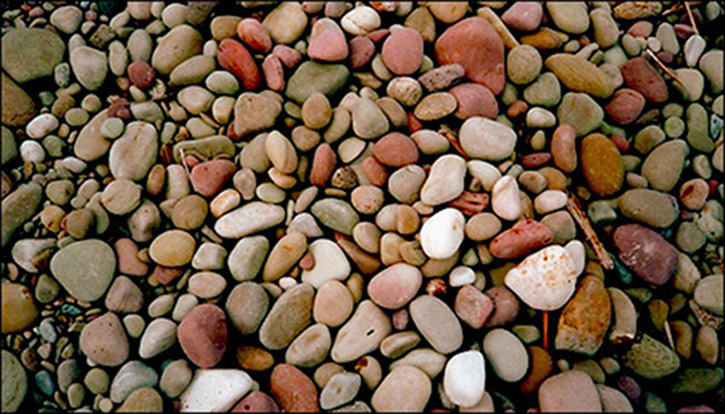

Another old problem at the Sandy Pond beach is one of nature's making: rocks. During the 40 years that I visited Sandy Pond, the three-plus miles of beach from the parking lot north to the channel was relatively rock free. South of the parking lot? That was another matter. In that direction there was no beach, only millions of smooth, round rocks as far as the eye could see. I foolishly thought this, too, was nature's work, but it turned out that one of the pre-season duties assigned to Sandy Pond lifeguards in the 1950s and later was to pick up rocks from the beach and dump them along the shore to the south. These rocks (photo, above) come in several colors and sizes and are quite beautiful. Walking on them wasn't fun, but we always made it a point to do just that in order to collect a selection of rocks that we'd take home at the end of each vacation. That was then. Now is another matter. It is illegal to collect anything on state lands — including these rocks. That's a shame because a small pailful of those rocks is the ultimate Sandy Pond souvenir. I'm not sure any harm would be done by allowing people to take a few. There were so many rocks on the beach in 2002 that the county had to haul away several tons of them in order to open the park on time. SANDY ISLAND BEACH remains important because it is part of the Eastern Lake Ontario Dune and Wetland Area, a 17-mile stretch of shoreline. The area is considered the only significant freshwater dune site in the northeastern United States. At least three rare or endangered plant species are native to the dunes, while the wetlands support 14 more rare plants. The system supports eight rare animals and eleven significant habitat types. Visitors are still permitted to walk from the beach to the channel – provided they do it along the waterline and not attempt to climb the sandhills where even more cottages have been built. Trespassers will be prosecuted. Most Sandy Pond summer residents don't have to walk to the channel. They visit by boat and do their swimming at what is widely (and obviously) known as Boaters Beach, though the official name seems to be Sandy Pond Beach. This beach remained relatively unscathed during the rise and fall of Sandy Island Beach in the 1950s and '60s, though there have always been periods when the channel becomes so shallow that some boats are unable to use it. Much of the area south of the channel is now owned by the state and is off limits to visitors. For more information, check out nysgdunes.org SANDY POND is a beautiful place, though the struggle to survive is constant. Over the years efforts have been made to convince the federal government to dredge and establish a steel and/or concrete-reinforced channel that can withstand the elements. As far as I know, such an idea has never been seriously considered. On the other hand, I believe such a channel, while aiding fishermen and those with large water-going toys, would deface an area that owes much of its considerable charm to a stretch of beach so primitive that visitors can imagine they are in another world or a different century. Either one is where a vacationer often wants to be. The only member of our family who was a true Pond Person was my late cousin Loretta Kane Orlando Lindsey. She and her husband owned some property at Sandy Pond and she loved going there each summer. The rest of us never had the complete Pond Experience — which includes such things as spending many hours with members of your family in the fall building a dock that will last forever . . . only to have it destroyed by the elements during the long winter that often begins in October. One big change that I noticed on the Google map of Sandy Pond is a road that runs along the southwestern shore, at the bottom of the sandhill. I didn't think such a thing was possible. If the last cottage we rented is still being used, the occupants no longer need a boat to reach it. Automobiles — and a power line, I assume — are now in evidence. Sandy Pond's property owners are a tough, wonderful bunch and I thank them for keeping alive a place that holds fond memories for thousands of people. Certainly I am grateful my parents discovered it. Were I within striking distance, I'd still be vacationing there. Paul Grecco Jr., son of my cousin Sandra, and now a resident of Florida, spent two weeks at Sandy Pond a few years ago and had a wonderful time. Sandra's sister, Linda, still visits the Pond occasionally. For those interested in finding out more about Sandy Pond, here are some websites you should visit: |

|

||||||||||||

| Sandy Pond flashback: More photos | ||||||||||||

| HOME • CONTACT | ||||||||||||

all Sandy Pond channels since then, the original was not supported by steel or concrete and was at the mercy of the weather, which is particularly cruel in this area. During one horrific storm in the 1950s, rain, wind and Lake Ontario surf created its own channel (which at least one newspaper account described as an improvement over the first one dug by the state).

all Sandy Pond channels since then, the original was not supported by steel or concrete and was at the mercy of the weather, which is particularly cruel in this area. During one horrific storm in the 1950s, rain, wind and Lake Ontario surf created its own channel (which at least one newspaper account described as an improvement over the first one dug by the state). or newspaper for two weeks. We read a lot, played cards and board games. Talked and acted silly.

or newspaper for two weeks. We read a lot, played cards and board games. Talked and acted silly. The bigger cottage had a kitchen, dining room and living room downstairs; upstairs were four small bedrooms with paper-thin walls. The first floor was at road level, a car-width off County Highway 15, which continued past the cottage and followed the pond shoreline south by southwest around a curve until it deadended at a small bridge which marked the start of the desert walk to the beach.

The bigger cottage had a kitchen, dining room and living room downstairs; upstairs were four small bedrooms with paper-thin walls. The first floor was at road level, a car-width off County Highway 15, which continued past the cottage and followed the pond shoreline south by southwest around a curve until it deadended at a small bridge which marked the start of the desert walk to the beach. Disposable Age had arrived. Trash barrels were quickly filled to overflowing with cans, plastic bags, wrappers, paper cups and food leftovers. The word went out to flying insects everywhere: All you can eat at Sandy Pond!

Disposable Age had arrived. Trash barrels were quickly filled to overflowing with cans, plastic bags, wrappers, paper cups and food leftovers. The word went out to flying insects everywhere: All you can eat at Sandy Pond! Pond debut. My brother-in-law has to work, but he’ll spend two weekends at the cottage. My family is invited, too. Okay, says my wife, but only for a brief visit. Very brief.

Pond debut. My brother-in-law has to work, but he’ll spend two weekends at the cottage. My family is invited, too. Okay, says my wife, but only for a brief visit. Very brief. that includes alewives. Nature is now more in balance; there’s food enough for all of the fish, even, it seems, the downsized population of alewives. For more than 10 years the Lake Ontario beaches were relatively free of dead fish, though I've been told that in recent years they were noticeable once again, though nowhere near the eyesore they were in the '50s and '60s.

that includes alewives. Nature is now more in balance; there’s food enough for all of the fish, even, it seems, the downsized population of alewives. For more than 10 years the Lake Ontario beaches were relatively free of dead fish, though I've been told that in recent years they were noticeable once again, though nowhere near the eyesore they were in the '50s and '60s. Each hooked a fish I’d never seen before. The locals referred to it as a ling, but I later learned it is more widely known as a bowfin, the sole surviving species of an ancient fish family.

Each hooked a fish I’d never seen before. The locals referred to it as a ling, but I later learned it is more widely known as a bowfin, the sole surviving species of an ancient fish family. much fun. Out front, about 50 feet away, was a dock that extended into the pond. In back was a secluded Lake Ontario beach, just beyond a couple of small sand dunes – dunes that hadn’t existed 30 years earlier.

much fun. Out front, about 50 feet away, was a dock that extended into the pond. In back was a secluded Lake Ontario beach, just beyond a couple of small sand dunes – dunes that hadn’t existed 30 years earlier. I've heard about a woman who so loved Sandy Pond that she told her family that upon her death she wanted to be cremated, with her remains scattered over her favorite fishing spot. I understand her feelings. Any Pondaholic would. We're like members of a cult, irrationally devoted to a state of mind that we found at a certain place at a certain age in a certain era. This may be particularly true for people who grew up in the 1950s.

I've heard about a woman who so loved Sandy Pond that she told her family that upon her death she wanted to be cremated, with her remains scattered over her favorite fishing spot. I understand her feelings. Any Pondaholic would. We're like members of a cult, irrationally devoted to a state of mind that we found at a certain place at a certain age in a certain era. This may be particularly true for people who grew up in the 1950s.