This interview was doomed as soon as my boss abruptly informed me to expect a call from Martha Raye at my home that evening. There was no discussion about whether my wife and I might have made any plans. At 7:30 or so, my home phone would ring and the voice on the other end would belong to Martha Raye who would promote her upcoming appearance at the Warwick Musical Theater, which from the 1960s until the 1980s furnished Rhode Islander with big-name summer entertainment.

In 1969 the theater was fazing out productions of musicals in favor of Las Vegas-style entertainment featuring a headliner (Jack Benny, for example) and an opening act (in Benny's case it was singer Shani Wallis).

Raye, on the other hand, was starring in "Hello, Suckers," a musical supposedly headed for New York. Ticket sales were slow, which upset Buster Bonoff, who ran the theater-in-the-round. Bonoff was accustomed to receiving lots of space on the Journal entertainment pages, which was one reason my relationship with him got off to a rocky start. That and some negative reviews I had given his shows. We eventually became friends of a sort, though even then I never escaped the feeling that our bond was 70 per cent business, 30 per cent personal. Giving Bonoff his due, he was skilled at what he did, was very generous and gracious, and he had a wonderful family, all of whom participated in running the theater. During the winters they had a similar operation in Phoenix.

Anyway, Raye's musical was based on the life of "Texas" Guinan, the colorful woman who during Prohibition ran "The 300 Club," a popular New York City speakeasy. She also acted as emcee for the club's entertainment, which included a mix of top notch musical performers and young, scantily clad dancing girls. Her signature phrase, which opened every show, was "Hello, suckers!"

The way the interview had been dropped in my lap, plus the lack of information available at the time about Raye, plus my own dislike for her style of entertainment and a decided lack of professionalism on my part produced one of the shortest phone calls I ever had from an entertainer.

Raye was upbeat when she greeted me, but her words set my teeth on edge because they suggested I had initiated the interview because I was just dying to talk to her. I reacted badly, which bruised her feelings, and soon we were saying things that made a bad situation worse. Result: there was no interview. And by the time I accepted the idea that the fault was entirely mine it was too late.

The good thing, as far as I was concerned, is that Bonoff temporarily didn't want me anywhere near his place. Someone else reviewed the show, most likely our theater critic, Brad Swan, who may have regretted that he hadn't gone on vacation that week.

From what I've found on-line, "Hello, Suckers" (which may have been spelled without the comma) ran only four weeks on the summer theater circuit before it folded. Even at that, its brief schedule was logistically strange. Three of the stops made sense – Westbury, NY; Warwick, RI, and Wallingford, CT. Those last two operated like sister theaters. A performer booked at one was usually booked at the other, either the week before or the week after. These three venues were part of a circuit that also included a theater in Cape Cod and one in Ohio, near Cleveland. For some reason, "Hello, Suckers" went from Westbury to a theater in Fort Worth, TX, before going to Warwick and, finally, to Wallingford.

Martha Raye deserved better treatment for her phone call. In many ways she was a remarkable entertainer, first providing musical and comedy relief in movies, then in the middle 1950s moving on to her own television series (that featured former boxer Rocky Graziano as her boyfriend), and through three wars she entertained our troops, often nursing the wounded. In 1969 her efforts on behalf of our soldiers earned her the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, presented during the Academy Award ceremonies.

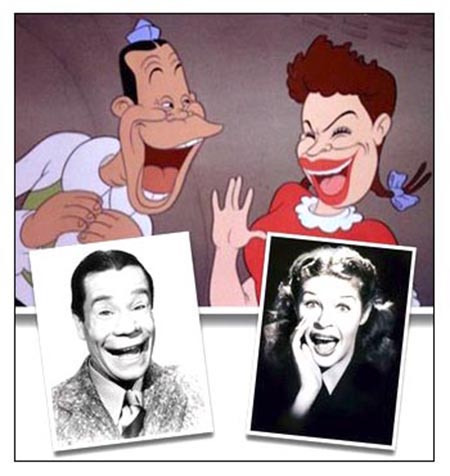

She was 20 years old when she made her first movie, "Rhythm on the Range" with Bing Crosby and Frances Farmer. She was busy for the next six years in a series of musical comedies, several of them with Bob Hope. Known for a mouth that seemed to dominate her face, Raye inevitably was teamed in a couple of movies with Joe E. Brown, whose mouth was even larger. (In Googling the two of them I found a 1938 Walt Disney "Silly Symphony" cartoon, "Mother Goose Goes Hollywood," in which caricatures of Raye and Brown. below, were teamed because of their mouths.)