| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

Ida May Hanson of Columbus, Nebraska, was brutally killed in mid-May, 1933. But until late September, 1934, the only person who knew for sure Miss Hanson was dead was the man who murdered her. Charles W. Neal, a man of at least three names and ever-changing occupations, had reason to think he'd gotten away with murder. Perhaps he would have if it weren't for two optimistic gold-seekers and a small-town Colorado sheriff who was determined to solve a case that had landed in his lap. Sheriff Ed Vinyard lived in Cripple Creek, a gold-rush town that flourished in the 1890s, but was barely alive by 1933. Things were very slow for the lawman, and he was able to put a lot of time into a case that for fifteen months did not have a name to go with the body that had been found. The killer had disposed of the body a few miles from Cripple Creek, dumping it in the mountains where he figured it would not be found for a long time, if at all because it had been many years since anyone had found gold in the area. That didn't discourage folks who believed other discoveries were possible. Paul Rhodes and Donald Good were two such prospectors, and on June 4, 1933, less than a month after the murder, they were in the mountains near Florissant, Colorado, a tiny settlement north of Cripple Creek. They came upon a startling sight in a rubble-filled trench atop a mountain ridge. Sticking up from the rubble was a human leg. The two men notified Sheriff Vinyard. An article from American Weekly (June 9, 1935), a Sunday newspaper supplement, described what happened next: |

|

|

|

An investigation revealed the killer used gasoline to burn the body and clothes of the victim, but apparently he feared flames and smoke would attract attention. So he threw rocks and dirt onto the body, hoping a smoldering fire would not be noticed, but would destroy enough evidence to prevent identification should the body be found. Before starting the fire, he took time to strip labels from the woman's clothing. One thing that would trip him up was what remained of the shawl he placed over the body. Enough of the clothing rsemained to indicate the woman had the means to buy expensive, fashionable items. She was five-feet-seven-inches tall, weighed about 130 pounds, had blue eyes and dark brown hair, with streaks of gray. It was estimated she was about forty years old. Perhaps it was the age estimate — off by 16 years — that delayed identification of the body for so long. That and the location of the body. It's unlikely relatives of 56-year-old Ida May Hanson, who sold hats at her shop in Columbus, Nebraska, thought the woman's remains would be found in the rugged mountains near Cripple Creek, Colorado.

Until late September, 1934, Sheriff Ed Vinyard had no idea the body discovered in his back yard belonged to Ida May Hanson. That's why her death wasn't reported until 16 months after she had been killed. That also may be the reason this murder received little newspaper coverage. If it weren't for three American Weekly articles, I wouldn't have learned of the interesting case. The articles appeared in 1935, 1943 and 1953. Sheriff Vinyard might never have found the name of the murder victim if it weren't for Dr. Glen S. Chafee, a Cripple Creek dentist, who had an idea after he took pictures and X-rays of the woman's mouth. Her crooked teeth had required extensive dental work, so extensive that Dr. Chafee believed the dentist who did that work would well remember the patient. The dentist prepared a detailed description of his findings, and Sheriff Vinyard sent copies to a convention of the Colorado State Dental Association. The report was given to more than 300 dentists, who were asked to compare the dead woman's dental work with anything they had done. A copy of Dr. Chafee's report also was published in a nationally distributed dental magazine. Months passed, during which Sheriff Vinyard studied reports of 192 missing women. None was a match for the body found near Cripple Creek. Finally, that magazine article came to the attention of Dr. A. P. Taylor, a dentist in Lincoln, Nebraska. The work described was similar to what he had done for a patient in 1931. That patient was Ida May Hanson. Dr. Taylor then contacted the woman's brother, Joel Hanson, of Osceola, Nebraska. On September 24, 1934, Joel Hanson wrote to Sheriff Vinyard, suggesting the unidentified body might be his sister, Ida May. Three days later, Hanson went to Cripple Creek, with dental X-rays provided by Dr. Taylor. Those X-rays appeared to be a match for mouth of the body discovered by the two gold prospectors. What clinched it for Joel Hanson was the shawl found on the body. From that American Weekly article on June 9, 1935: |

|

|

|

Within minutes, the stalled case suddenly accelerated toward its solution. The key was something Joel Hanson remembered about the only man in his sister's life. He called himself Clarence Neal, and he had a crippled left hand. Hanson said Neal showed up in Columbus, Nebraska, in July, 1932, and befriended his sister at a Fourth of July picnic. After that, said Hanson, Ida May and Neal began seeing each other regularly, often taking automobile trips together until he abruptly left town in the fall. But, Hanson continued, Neal returned to Columbus in 1933, and within days, on May 9, Ida May went off with him in her automobile. She was wearing a valuable diamond ring — hers, not one Neal had given her — and she had with her more than $11,000 in cash and securities. For Sheriff Ed Vinyard's response, it's back to American Weekly: |

|

|

|

What happened next is told in this newspaper account. Notice Ida May Hanson is referred to as a "girl." |

|

|

|

Neal came to Spencer last December from Omaha where, he said, he was engaged in selling bonds for the First Mortgage Acceptance Corporation. He since has been in the automobile business in Spencer and Chicago. When questioned in Cripple Creek, Neal had no documentation for these alleged purchases. As mentioned in the Iowa City article, he claimed the bonds had been stolen from him while he was driving to Omaha. When Neal tried to detail the purchase of the bonds, he tripped himself up, claiming the deal was concluded at his Chicago office on May 24, 1933, which was at least nine days after her death. While the case against Neal was entirely circumstantial, the state of Colorado went ahead in March, 1935. The jury deliberated 41 hours before declaring Neal guilty of murder in the first degree. Neal was sentenced to life imprisonment, but died on May 20, 1936, after contracting pneumonia. IT SEEMS puzzling that Ida May Hanson's siblings didn't press harder in 1933 to locate their sister. Perhaps because Ida May Hanson was a 56-year-old spinster in 1933, her older brother, Joel, and her five younger sisters had given up worrying about a woman they considered independent, somewhat headstrong and no doubt tired of people asking if she was ever going to marry. A friend of the woman told police Clarence Neal was the only man Ida May Hanson ever loved. Which makes it even weirder that some family members received a telegram, signed Ida, claiming she was married to an engineer and headed for South America. (Later it was proved the telegram was sent by Neal.) In all, a very strange case. It would make for an interesting episode of "Forensic Files." |

|

| HOME • CONTACT | |

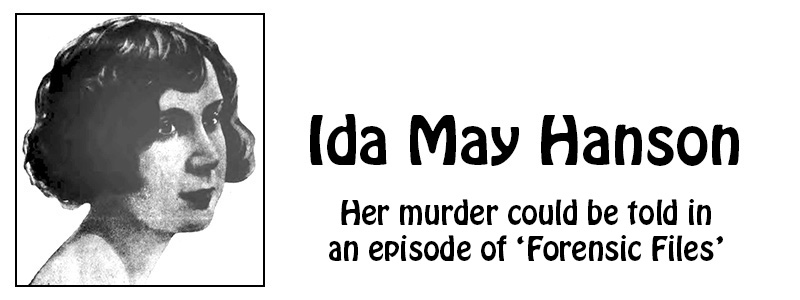

Ida May Hanson must have seemed much younger than she was. Even after her identity was established, some newspaper reports said she was only 35 years old. A photograph (right) purported to be taken just before her fateful trip to Colorado certainly doesn't appear to be that of someone born in 1877.

Ida May Hanson must have seemed much younger than she was. Even after her identity was established, some newspaper reports said she was only 35 years old. A photograph (right) purported to be taken just before her fateful trip to Colorado certainly doesn't appear to be that of someone born in 1877.