|

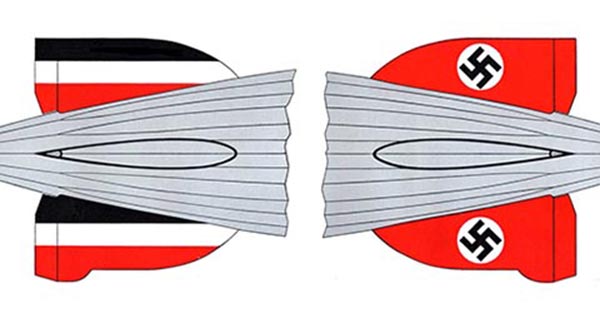

Hugo Eckener became a world celebrity through his association with zeppelin aviation, which in the early 1930s was the fastest, most comfortable way to travel great distances.

He studied psychology in college and earned a doctoral degree. According to a biography on airships. net, Eckener "had no formal training in physics, engineering, or aeronautics." He was working as a journalist in 1900 when he was given a career-changing assignment — to cover the second flight of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. This was his first look at an airship, and before long he went to work for Zeppelin as a writer and publicist.

He became more interested in the doing than the writing, and by 1911 he was given command of a zeppelin. His new career got off to a rocky start when a gust of wind tore the ship away from the ground crew before it even left the hangar. The ship smashed against the hangar roof and the passengers and crew had to be evacuated. It is believed this incident prompted Eckener to be unusually cautious and a stickler for safety, something evident in one of the stories below, about the Graf Zeppelin landing in Akron, Ohio.

By 1933, Eckener was 65 years old. He was skeptical about the new Nazi regime, and this, plus his age, led to his being removed as the head of Germany's zeppelin operations. So 1933 marked what might be considered Eckener's grand farewell tour, which included a brief stop at the world's fair in Chicago.

|

| |

Syracuse Journal, July 15, 1933

BERLIN (INS) — Negotiations were underway today to send the Graf Zeppelin on another flight to New York.

Dr. Hugo Eckener, commander of the giant dirigible, said the trip probably would be made in October as an extension of the regular passenger and mail service to South America. |

|

|

Syracuse American, September 24, 1933

AKRON, Ohio (INS) — A Magellan of the skies, Dr. Hugo Eckener, grizzled skipper of the German globe-trotting dirigible, Graf Zeppelin, last night foresaw the start of transoceanic airship service between Europe and the United States in the spring of 1935.

He solemnly delivered his observation after two days of conferences with Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation officials.

The latter promised, it was reported on the highest authority, that Goodyear would build the third necessary ship for the trans-Atlantic fleet if Congress can be induced to enact laws to allow the awarding of air mail contracts to craft of that type.

Dr. Eckener said he would seek permission from the United States government to use the Naval hangar at Lakehurst,, New Jersey, as the American terminal of the proposed line. During winter months, when weather conditions prevent the dirigible from flying northward to New Jersey, the ships will be moored at Miami, Florida, he declared. |

|

| |

Syracuse Journal, October 10, 1933

FRIEDRICHSHAFEN, Germany (INS) — The German passenger dirigible Graf Zeppelin returned today from Pernambuco, Brazil, after a record-breaking flight of 71 hours. Mechanics immediately began overhauling the giant ship for its flight, beginning Saturday, to Rio de Janeiro and thence to Chicago to visit the world’s fair. |

|

| |

Syracuse Journal, October 25, 1933

AKRON, Ohio (INS) — Running the gauntlet of every kind of weather during the last 30 hours, the German dirigible, Graf Zeppelin, made a “happy landing” here today when its veteran skipper, Dr. Hugo Eckener, declared that he would rather fly a hydrogen-filled airship than the helium inflated craft the United States now uses.

Encountering thunder storms, summer sunshine, rain, sleet, snow and heavy winds on its flight from Miami, Florida, to Akron as an anti-climax to its successful trans-oceanic voyage, the Graf was brought to the ground approximately 31-1/2 hours after it had taken off from the Florida city.

Far from displeased at the performance of his craft, Dr. Eckener smiled happily as he alighted at the airport here after the ship had been “barooned” in the air for approximately 10 hours by a fitful 40-mile-an-hour gale that roared out of the north, bringing intermittent sleet, rain and a blizzard-like snow.

Dr. Eckener declared that he could have landed the Graf at any hour he wished last night, despite the inclement weather. He explained, however, that a cross-wind was blowing against the hangar and that the ship would have been forced to ride out the night at a mooring mast on the field if he had elected to land when the ship was first sighted at 7:27 o’clock last night.

He said he preferred to remain in the air in order to give his passengers a good night’s rest. The ship finally was docked within the hangar at 6:05 a.m. today although it made contact with the ground crew an hour earlier. At the time of the landing, the wind had abated to about 17 miles an hour, but a sharp, brief snow beat against the silvery hulk of the airship.

Dr. Eckener, on land, granted an interview, the highlight of which was his statement that he preferred to fly a hydrogen-filled Zeppelin. He declared that such a ship could be maneuvered more easily. He refused to elaborate on the declaration, waving away further questions as he left the airdock for a downtown hotel for several hours sleep.

The grizzled commander said the delayed landing here would not interfere with the projected flight to the World Fair at Chicago. He said the ship would take off at 11 p.m. tonight, arriving in Chicago tomorrow morning at 9 o’clock. He said the craft would be landed for a half-hour if the weather is favorable. It will return to Akron about dusk tomorrow and take off for Germany via Spain on Saturday morning. |

|

|

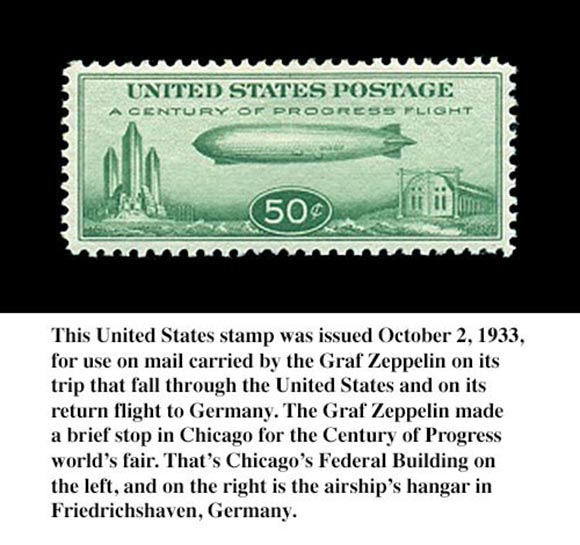

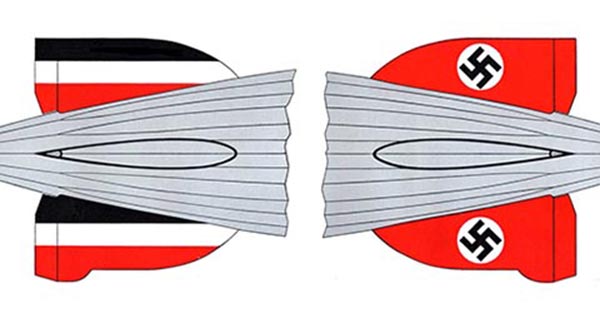

While Graf Zeppelin’s appearance was one of the highlights of the Chicago Fair, the swastika-emblazoned ship, which was viewed as a symbol of the new government in Berlin, triggered strong political responses from both supporters and opponents of Hitler’s regime, especially among German-Americans. The political controversy muted the enthusiasm that Americans had previously displayed toward the German ship during its earlier visits, and when Eckener took Graf Zeppelin on a aerial circuit around Chicago to show his ship to the residents of the city, he was careful to to fly a clockwise pattern so that Chicagoans would see only the tricolor German flag on the starboard fin, and not the swastika flag painted on the port fin under the new regulations issued by the German Air Ministry.

|

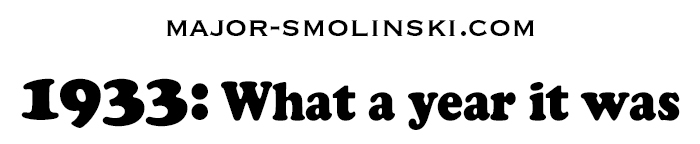

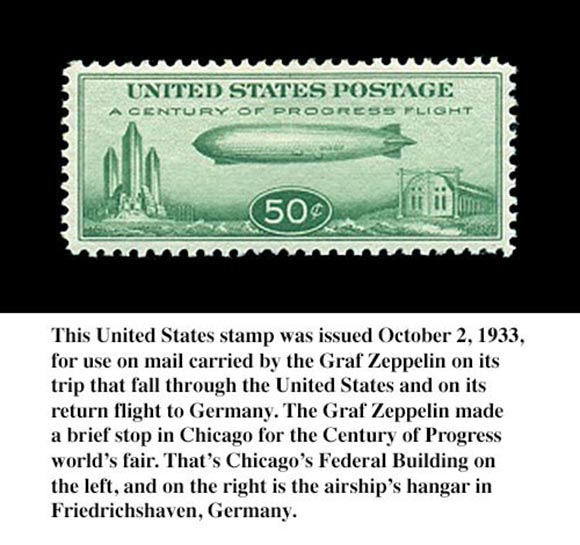

Eckener insisted that proceeds from the commemorative stamp (above) be split between the United States Post Office and the Zeppelin Company. This delayed President Roosevelt's approval of the stamp, but he finally consented.

However, controversy broke out when the Hitler government ordered that the Nazi swastika be displayed on the Graf Zeppelin, and it was, on the port fins of the airship. The tricolor German flag remained featured on the starboard fin. (This, I believe, was not the case with future German airships, which displayed the swastika on both sides.)

There was a rally held in Chicago to coincide with Eckener's visit, and while that visit was brief, the commander attended the rally, but clearly was not enthusiastic about the event, which was used to promote America's National Socialist sympathizers. (The users were dressed as storm troopers.)

Eckener's obvious discomfort — plus that clockwise stunt with the Graf Zeppelin — annoyed the Chicago Nazis, some of whom were German agents, and they sent word to the Gestapo that, in their opinion, Eckener was disloyal.

|

|

Here's a recreation of the tailfins of the Graf Zeppelin during its 1933 visit to The Century of Progress, Chicago's world's fair.

|

| |

Syracuse Journal, October 28, 1933

AKRON, Ohio (INS) — Intent upon making a record crossing of the Atlantic, the German dirigible, Graf Zeppelin, took off from the municipal airdock here and headed for Germany shortly before 5 a.m. today.

The Zeppelin, under the command of its veteran skipper, Dr. Hugo Eckener, circled over downtown Akron in a farewell salute and then pointed due east for Washington, D. C. Dr. Eckener declared he hoped to fly over the national capitol this afternoon.

After flying over Washington, the dirigible is expected to point due east for Seville, Spain, then fly directly to its dock in Germany.

Departure of the air cruiser was marked by ideal weather and brilliant sunshine, in contrast to the sleet, rain and snowstorm that marooned it in the skies for 10 hours before it was able to land after its arrival here Tuesday.

Since then the ship made a successful flight to the Chicago world fair and returned to the airdock here on Thursday. Dr. Eckener said he hoped to be back home on Tuesday.

Syracuse American, October 29, 1933

NEW YORK (Universal)— The Graf Zeppelin, returning to Germany after a visit to the Chicago world fair, struck out over the Atlantic at Cape May, New Jersey, shortly after 3:30 p.m. yesterday.

Droning under clear skies, with practically no wind, the huge German airship was maintaining her course on a direct line to Seville, Spain.

With her commander, Dr. Hugo Eckener, determined to establish a new record for the Atlantic crossing, the craft, veteran of several years of transoceanic flying, was soaring at a speed of approximately 70 miles an hour.

At 9 p.m. the Graf reported her position by radio, approximately 387 miles due east of Cape May.

The ship carried 24 passengers, several of them Americans, besides Dr. Eckener and a crew of 47, and a heavy consignment of mail.

Niagara Falls Gazette, November 2

BERLIN (AP) — Air Minister Goering today sent his personal congratulations to Commander Eckener, who brought the Graf Zeppelin to a landing at Friedrichshafen early today, completing the return trip from the United States.

The Graf Zeppelin was forced to cruise over the airfield for some time before landing, because of rain.

Goering said the return from the fiftieth ocean crossing had “contributed toward restoring German prestige in the entire world and the awakening of the German people to an unshakable confidence in their own ability.” |

|

| |

Eckener had little influence over Germany's zeppelin program by 1936 when the Hindenburg was built and ready to be tested. Captain Ernst Lehmann was commander of the much-publicized airship, and Eckener was highly critical when Lehman canceled test flights to take the Hindenburg on a propaganda flight, when the ship was damaged during unfavorable weather conditions.

Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, furious at Eckener's criticism, ordered that the onetime national hero could no longer be mentioned by the German press, but Herman Goering intervened on Eckener's behalf because he believed the criticism was technical, not political.

But the days of the zeppelin were number after the Hindenburg burst into flame on May 6, 1937, over Lakehurst, New Jersey. Eckener was in Austria at the time, but he traveled to New York by ocean liner as part of a German investigating commission.

Eckener's conclusion, after studying witness reports and examining the wreckage, was that Captain Max Pruss, in charge of the Hindenburg on its fatal voyage, had stressed the ship during a sharp S-turn, causing a bracing wire to snap and slash a gas cell, which triggered a chemical reaction that caused the explosion.

Unlike several other zeppelin veterans, Eckener believed the time for airships was over. He outlived the Nazi regime and died at home on August 14, 1954. He was 86 years old.

|

| |

| HOME • CONTACT |

| |

|