The recent death of Jim Brown prompted me to dust off some old memories, including the comical, only-in-Syracuse way I first heard about the man who years later would widely be hailed as possibly the greatest running back of all-time and the greatest athlete ever.

He was a freshman at Syracuse University in the fall of 1953. I was a high school junior in Solvay, New York, a village that abuts the west side of the city of Syracuse. I considered myself a huge Syracuse football fan, so after one of my friends, Bob Ranalli, attended the game between the Syracuse frosh and a team from Wyoming Seminary, a Pennsylvania college preparatory school, I asked Bob for his observations.

Bob's only comment was that the player who kicked extra points for Syracuse was named Brown. (He didn't even mention the quarterback was Lou Iannicello, a Solvay High graduate."

ONLY a very old Syracuse fan would understand the significance of the remark about kicking extra points, which had less to do with diminishing  Brown's role than with the recent history of Syracuse football. It also was a comment on the state of football in the early 1950s, which some would say was the way the game should be played. Brown's role than with the recent history of Syracuse football. It also was a comment on the state of football in the early 1950s, which some would say was the way the game should be played.

Seems hard to believe, but it was 70 years ago when Brown was a 17-year-old Syracuse freshman. This was before the Gogolak brothers, Pete and Charlie, Hungarian immigrants who attended Cornell and Princeton, demonstrated the advantages of having soccer-style place kickers. Until the Gogolaks came along, extra points were an adventure and field goals a rarity, and both were attempted by regular members of the team, not specialists who remained on the sidelines until they were called upon to kick.

Syracuse fielded excellent football teams in the 1920s, but went downhill in the ’30s, and hit rock bottom in 1948 when it won only one game, against Niagara University, whose officials decided that if their school couldn’t beat Syracuse, they might as well drop football from their program, which they did.

One of Syracuse’s few bright spots in the 1940s was provided by a little-used halfback from Scarsdale, N. Y., named George Brown, who, in 1946, successfully kicked 20 extra points in a row, and continued his streak in 1947 until he injured in the third game. As far as I know, he attempted only one field goal during that period, from 30 yards away, and missed.

Because straight-on place kickers weren’t particularly accurate and, generally, did not kick for great distance, coaches almost always eschewed field goal attempts when their teams were within or close to the co-called “red zone.” Instead, on fourth downs, they attempted to make first downs or score touchdowns. Frankly, I thought this made for more exciting games.

ANYWAY, George Brown was one of the big names in Syracuse football during the doldrums. So, in 1953, when Bob Ranalli told me Syracuse had another place kicker named Brown, it was considered a step in the right direction for the football program, especially for fans who offered an hilarious rationalization for the school’s 61-6 defeat in the 1953 Orange Bowl against Alabama.

The Crimson Tide scored quickly, taking a 7-0 lead. Syracuse, whose emergence from the doldrums was accomplished too quickly under Coach Ben Schwartzwalder, wasn’t ready for prime time, but the team retaliated on its next possession.

Alas, the attempted point after touchdown was missed, and that, according to some fans, was what took the heart out of the Syracuse team. Of course, realistic Syracuse supporters downplayed the importance of the missed extra point, knowing that had it been successful, the final score would have been 61-7.

UNCERTAIN, straight-on place-kicking wasn’t the only big difference in college football in 1953. After experimenting with two-platoon rules that created separate line-ups for offense and defense, the colleges went back to the single platoon, with limited substitution that meant most players were used on offense and defense. (In his senior year, linebacker Brown made a touchdown-preventing tackle on an Army runner that preserved a Syracuse lead in what became a 7-0 victory.)

And while freshman had been eligible to play varsity sports during and for a few years after World War Two, in 1953 colleges had to have separate, freshman teams that played short schedules. I found four games for the Syracuse frosh in 1953 — a win over Army, losses to Wyoming Seminary and Colgate, and a contest with Cornell that was postponed because of snow.

Thus Jim Brown did not get a whole lot of attention during his freshman year, and if there were a transfer portal in those days, he might well have switched schools, though there were some Syracuse alumni from Long Island who had seen Brown play at Manhasset High School, and pressured him to remain in Syracuse. These alumni knew something that apparently was slow to occur to Coach Schwartzwalder — Jim Brown was special. (One of Syracuse's assistant coaches was Rocky Pirro, a Solvay High graduate who lived in the village and attended St. Cecilia's Church every Sunday. My father often talked to Rocky after mass, and asked about the team. He never once mentioned being excited about a freshman named Jim Brown.)

HOWEVER, on September 25, 1954, my father and I met someone who was super-excited about Brown. We were in the stands at Archbold Stadium, waiting for the start of the Syracuse football season against Villanova. My father and I had started attending every home game in 1950, and we’d become fans of an undersized halfback named Sam Alexander, who for two seasons was pretty much been limited to returning kickoffs for three seasons. When we noticed Alexander listed as the starting left half back against Villanova, we mentioned it out loud, saying we were glad he finally was getting his chance to shine.

That attracted the attention of a man sitting directly in front of us. He turned around and advised us to enjoy Alexander while we could. “There’s a sophomore named Brown, and he’ll soon be starting instead of Alexander. Brown’s something else, wait and see.”

The man was right, of course, but Brown did not become a starter until late in the eight-game season, and that was because of an injury, not to Alexander, but to a running back named Art Troilo, who had taken over as a starter.

Thus, in the sixth game of the season, against Cornell, Jim Brown emerged as the starter and clearly the best running back on the team, and one couldn’t help but wonder what took coach Ben Schwartzwalder so long to recognize the obvious. Syracuse lost to Cornell, 14-6, but Brown gained 151 yards on 17 carries, and scored his team’s only touchdown on a 53-yard run.

With Brown a starter, Syracuse won its last two games, against Colgate and Fordham. (Syracuse was gradually toughening its schedule at a time schools had to decide which way to go with their programs. To be fair, Colgate and Fordham, at one time, fielded football teams that could compete with anyone.)

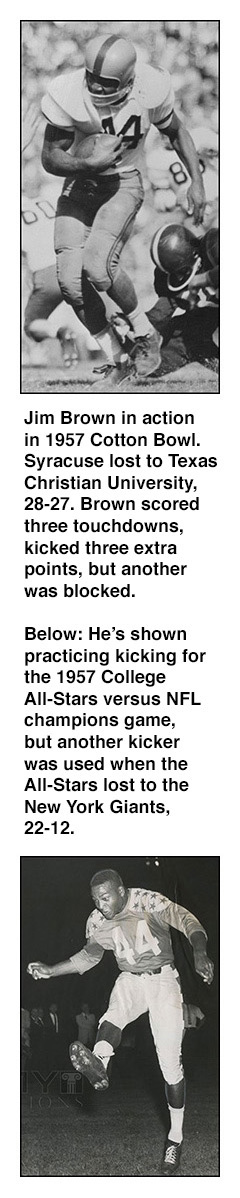

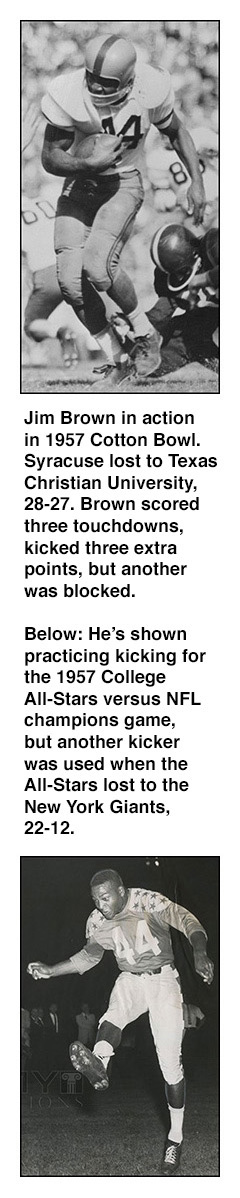

WHAT'S OFTEN forgotten by sports announcers when they go on and on and on about records being set by today’s players are some essential facts about those who competed in the 1950s and earlier. For example, Jim Brown played in only 25 games — eight regular season games in each of his three seasons, plus the Cotton Bowl against Texas Christian during his senior year.

Also, many teams, including Syracuse, ran most of their plays from a T-formation that featured three running backs, rather than today’s teams that primarily use one running back. Brown saw playing time in that first game, against Villanova, but shared running duties with no less than five other backs, including Alexander, Troilo, Bill Wetzel, Don Laaksonen and one of the most versatile players Syracuse ever had — Ray Perkins. (Sooner of later, it seems every team has a guy named Ray Perkins.)

Neither did Brown step right into the role of place kicker. Perkins kicked three extra points against Villanova, Laaksonen kicked the other one in a 28-6 win. Brown wasn’t the primary place kicker until late in the season.

IT WAS the evening of the Cornell game that Bob Ranalli and I had another Jim Brown moment. Accompanied by my cousin Tom Smolinski, Bob and I went to a movie in downtown Syracuse. We were standing in line for the nine o’clock showing, and Bob, who had just received an appointment to West Point, was talking about possibly playing football there. He wasn’t a big fellow — he stood five-foot-nine — and wasn’t sure he’d try out for the varsity or play for Army’s 150-pound team.

At that point, those who’d attended the seven o’clock showing filed out of the theater. Among them: Jim Brown, at least six inches taller and sixty pounds heavier than my friend. Just as Bob said he’d probably opt to play varsity football, Brown walked past us. Bob looked up at him, and without missing a beat said, “Then again, maybe I’ll stick with the 150-pound team.”

Another high school friend, Doug Forsythe, who was a sophomore at Syracuse University when Brown was a senior, remembers playing an early morning, on-campus pick-up basketball game that involved Brown on May 18, 1957. That's an important date in the legend of Jim Brown, because he had to leave the gymnasium to participate in a track meet against Colgate. Brown scored 13 points in that meet, winning the high jump and the discus, and finishing second in the javelin.

But Brown wasn’t finished. He then scored a goal and had three assists as Syracuse beat Army, 8-6, to conclude it first unbeaten lacrosse season since 1924.

BROWN ALSO lettered in basketball and was drafted by the Syracuse Nationals, then a member of the National Basketball Association, though I suspect that must have been a publicity gimmick. There wasn’t much chance Brown would fail to make it — and make it big — in the National Football League.

Also, I think the only member of that Syracuse University basketball team who had a chance to play in the NBA was Vinny Cohen, who so resembled Brown that it would be easy to confuse the two, except Cohen had a much better shooting touch. But Cohen wasn’t interested in playing professional basketball, and went on to become a very successful lawyer. He might well be remembered as the best basketball player in Syracuse University history if Dave Bing hadn’t come along a few years later.

BUT BACK to Jim Brown. What I enjoyed most about him on the football field was his demeanor. He showed no emotion, and always rose slowly after a tackle, almost hinting he might be hurt, but he never was. And when he raced or plunged into the end zone, he acted as though he’d been there before and expected to be there again.

He retired from pro football while still in his prime, and went into acting. Later he became better known as an activist, but his reputation was forever tarnished by incidents, mostly with women who accused him of assault. He was arrested seven times, but most times the charges were dropped. In all, he served only one day in jail, but paid fines, went to counseling and did several hundred hours of community service. He was twice married and had five children.

During Brown’s years at Syracuse, there were relatively few black college athletes, and his behavior was closely monitored, no doubt causing resentment on his part. While he spoke out about his treatment, he maintained a good relationship with the university for the rest of his life and is recognized as the best athlete the school ever had. Those who saw him play, say he was even better at lacrosse than he was at football. There's no denying he truly was one of a kind. |

Brown's role than with the recent history of Syracuse football. It also was a comment on the state of football in the early 1950s, which some would say was the way the game should be played.

Brown's role than with the recent history of Syracuse football. It also was a comment on the state of football in the early 1950s, which some would say was the way the game should be played.