| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

|

|

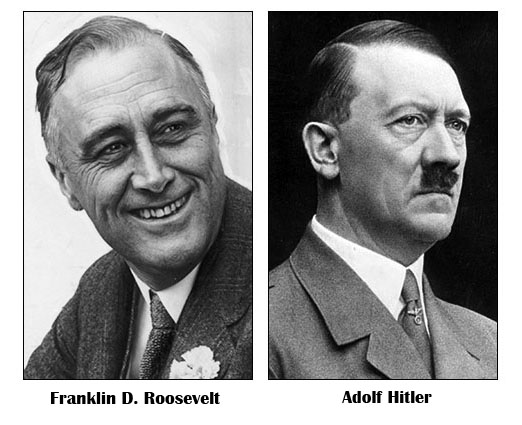

At home enormous change was brewing, while dark clouds appeared over Europe and Asia. It also was the year Franklin Delano Roosevelt became President, assuring the nation there was nothing to fear but fear itself. Also moving into the White House was Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, a First Lady who would have a tremendous impact on the country — and the world — long after her husband passed away. From Day One she was a force to be reckoned with. It also was the year Prohibition — the 18th amendment to the United States constitution — was repealed, as the first 36 states to vote on the matter agreed the experiment had failed, and that it was time to legalize alcoholic beverages once again. Those 36 states were what was needed to repeal the 18th amendment; oddly, on the day prohibition's fate was sealed, North Carolina and South Carolina gained distinction as the only states to vote against repeal. But they were too little and too late. As far as the rest of the world was concerned, especially Europe, the most memorable event took place early in 1933 when Adolf Hitler, whose Nazi party had been considered merely a nuisance a few years earlier, became chancellor of Germany. He wasted no time in creating controversy, especially through his views on racial purity and the Nazi campaign against Jews, but also through his insistence that Germany be allowed to re-arm itself. |

|

OBVIOUSLY, hindsight is almost always 20-20, but any reading of events in Germany and statements by Hitler, even as early as 1933, can leave you astonished that any nation willingly participated in the Berlin Olympics three years later. Unfortunately, countries that could have policed Hitler's activities were still reeling from the effects of World War 1 and preoccupied with a depression, which began late in 1929 and lingered for several years afterward. In France, more than elsewhere, there was a fear of Germany and a certainty Hitler was plotting a war of revenge for the humiliation his adopted country had suffered through the Versailles Treaty that ended what at the time was called The World War. Historians will tell you the war didn't actually end in 1919, that while the shooting may have stopped, the squabbling over terms of the Versailles Treaty continued right up until the Second World War. Events of 1933 bear that out, what with the United States upset with European countries not repaying their war debts, and England, France, Italy and Germany bumping heads over the re-armament issue. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union, which began the year still unrecognized by the United States, had become the proverbial 500-pound gorilla, always uninvited, but always present. (There were people who believed France was Europe's strongest nation, and a buffer against German aggression. Well-respeccted journalist Arthur Brisbane was so impressed by France's air force that he wrote, "It is no exaggeration to say that if France declared war on any country of Western Europe in the morning, all the cities of that country could be laid waste the same evening." Things didn't work out that way.) THEN THERE was Japan, which, in 1933, was the world's most overtly aggressive nation, already pecking away at neighboring China while it argued in favor of a larger navy that would challenge those of Great Britain and the United States. Many correctly predicted war between the United States and Japan was inevitable, but most Americans refused to believe it. The League of Nations, established to keep the peace, proved helpless in the face of serious challenge. Japan, Germany and Italy were particularly troublesome in 1933, and each country either walked out on the League or announced an intention to do so. Interestingly, United States conservatives wanted our country to avoid foreign entanglements; today's conservatives seem to believe we have a self-serving right to police the world. Also, despite our country's rather brief and limited experience as a world power, thanks to our late involvement in World War I, officials of several countries already were harsh in their criticism of the United States. Some even blamed our country for the emergence of Adolf Hitler, saying we somehow could have changed history had we joined the League of Nations and put some much-needed muscle into that organization. |

|

LIFE IN THE United States, meanwhile, was wilder and crazier than it was during the so-called Roaring '20s.. The violence and lawlessness of the '30s was unparalleled, thanks to the weapons available to outlaws, the vehicles used to commit the crimes, and a depression that fostered a desperation that made criminals out of people, who, in a better economy, would have been law-abiding workers. It also was an era that saw a widespread acceptance of the excuse used by many who claimed circumstances were to blame for their crimes, even murder. This acceptance did not extend to some who were accused of crimes, particularly those who were black. Lynchings increased in 1933 over previous years, though the victims in the year's most controversial vigilante hangings were two white men who had kidnapped a young man and almost immediately killed him. What made the case especially controversial was the California governor, who approved of the lynchings. The kidnapping and murder of the Charles A. Lindbergh baby in 1932 resulted in tough new laws throughout the country, but these laws failed to discourage criminals in 1933. The number of kidnappings and murders in 1933 was incredible, particularly when one considers the population of the country at the time was about 125 million, less than 40 percent of what it is now (about 320 million). Perhaps the fact the Lindbergh kidnapping hadn't yet been solved encouraged others to turn to abduction for ransom as a way to make a quick buck. Robbers who entered a bank might discover there was no money inside; those who abducted a wealthy person could demand a big payoff. They might not receive all that they asked for, but a lot of money did change hands in 1933. But unlike the Lindbergh kidnapping, the ones in 1933 were rather quickly solved. Another reason kidnappings seemed so numerous in 1933 was the way the press applied the label to so many crimes that would be described differently today. For example, criminals fleeing a robbery often stole automobiles, abducting drivers and passengers until they were a few miles away. In other words, carjacking. Bank robbers often took a few people with them,using them as shields until they were out of town. Newspaper accounts usually referred to these innocent people as kidnap victims, though they were set free less than an hour later, with no ransom asked. THE MOST terrifying experience for unlucky eyewitnesses involved a getaway technique employed by certain robbers who found a use for the running boards that were a part of most automobiles of the time. The robbers would force their temporary hostages to stand on the running boards and hold on for dear life while the robbers drove off. Shocking as it seems today, police in the 1920s and '30s often didn't hesitate to fire shots in a crowd. There are stories of car chases, with police in pursuit, in which gunshots were exchanged while gangsters used innocent people as shields on the outside of their vehicles. However, there also were a large number of kidnappings for ransom, including one in Kansas City that was unbelievably bizarre, though ultimately tragic, due to the sensitivity, vulnerability and, perhaps, the mental state of the victim, Mary McElroy, who bonded with her abductors almost immediately. Today her experience might be described as Stockholm syndrome; in 1933 it was considered weirdly inappropriate. Later she defended her kidnappers, argued not only against the death penalty, but against any punishment that included jail time. Three of the four men responsible for her kidnapping were caught and imprisoned. Two were still behind bars in 1940s when Miss McElroy committed suicide, leaving behind a note that indicated she remained bitter that her abductors had been punished. ALSO IN 1933 — perhaps the country's only father-and-son kidnappings. The son, Jerome Factor of Chicago, was kidnapped first, in April, and later returned unharmed. Theory was that gangsters were responsible. With the end of Prohibition in sight, some mobs turned to kidnapping to make money. That may not have been the case with Jerome Factor, but there clearly was something odd about the abduction of the young man's father, John "Jake the Barber" Factor, two months later. This obviously was the work of a mob, perhaps with the cooperation of the "victim," and the purpose was to frame a competing mob. And apparently the plan worked. This was one of many incidents in 1933 that seemed straight out of a Warner Brothers movie. Many of our best-known gangsters made news in 1933 — George "Machine Gun" Kelly, "Pretty Boy" Floyd, John Dillinger, Al Capone, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, among them. Clyde Barow and his brother, Marvin (aka Buck) were examples of another fairly common problem, especially in the South and Southwest. Their prisons were overcrowded, and inmates too often paroled, even pardoned, with no intention of going straight. Many prisoners who weren't released prematurely, had another alternative — they simply escaped. |

|

THE YEAR'S MOST dastardly and notorious United States crime was committed by a previously obscure former Italian soldier and anarchist, Guiseppe Zangara, who attempted to assassinate President-elect Roosevelt a few weeks before his inauguration. The shooting took place in Miami, but none of the bullets struck Roosevelt. Five persons were wounded, including Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak, who died three weeks later. Cermak's battle to survive the shooting was front page news, and his prognosis changed constantly — he was reported on the road to recovery one day, on the verge of death the next. Reading about his battle to survive reminded me of what our 20th President, James A. Garfield, endured after he was shot by an assassin on July 2, 1881, and held on until September 19, before he passed away, victim as much of poor medical treatment as a bullet. One assumes Cermak received much better care, but the result was the same. Years later some theorized Cermak, because of gangster warfare in Chicago, was Zangara's real target, but 1933 newspaper accounts indicate the assassin was gunning for Roosevelt, and was simply a terrible shot whose aim was made worse by the fact he had to stand on an unsteady chair to see his intended victim. For Zangara, justice was swift. Defiant to the end, he was executed shortly after Cermak's death. |

|

AMONG THE YEAR'S biggest newsmakers were the men and women who flew airplanes, dirigibles and balloons. Some of their stories were triumphant, some were tragic, and one became a month-long Siberian survival tale. However, by year's end, it was one of the world's most famous married couples, Charles and Anne Lindbergh, who had the longest and most-publicized flying adventure, doing so only a year after the tragic kidnapping and murder of their first child. But Lindbergh already was beginning to alienate people, thanks to his need for secrecy — and his silence. Ironically, it's when he began speaking out a few years later, expessing his admiration of Adolf Hitler, that Lindbergh became one of the most reviled men in America. |

|

LABOR DISPUTES disrupted nearly every industry in the United States. Some strikes were resolved quickly, some lingered for months, and many were marked by violence. Particularly unhappy in 1933 were farmers and dairymen who wanted price increases for the food they provided not only for Americans, but for people around the world. Coal miners also made headlines; their struggles would continue for years. Weather bounced from one extreme to the other during the year. Syracuse chalked up record low temperatures in the winter, record high temperatures in the late spring and summer. Hundreds of deaths were attributed to weather conditions. For some reason, residents of Chicago and surrounding towns were the most affected by the cold and the heat. The year also was marked by an unusually high number of tornadoes and hurricanes. There were disastrous earthquakes and floods, volcanoes erupted; Los Angeles experienced the worst fire in its history, while nearby Long Beach had one of the country's most damaging earthquakes. In March, Peru's president, Sanchez Cerro, was assassinated; there was political turmoil in Cuba which went through three presidents during the year; King Nadir of Khan of Afghanistan was assassinated, and there was an anarchist uprising in Spain in 1933, that was a prelude to the revolution that would rock the country in 1936. Paraguay and Bolivia waged war, so did Peru and Colombia; there was a revolt in Honduras, uprisings in Brazil and Argentina, and unrest in the Philippines. Meanwhile, in India, Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent civil disobedience was attracting attention and swaying opinion. |

|

RAILROAD CROSSINGS remained a problem throughout the country in rural areas where traffic was light, but the accidents often spectacular and tragic, such as one that occurred on a foggy December day in Crescent City, Florida, where a freight train slammed into a school bus crowded with children. Trains had a bad year even when crossings weren't involved. In May a train went off a bridge in Guatemala; two weeks later two subway trains collided in Brooklyn; in August, near Washington, D. C., a bridge weakened by flood waters, sagged and sent a Pennsylvania Railroad passenger train into the water. Five days later a Southern Pacific passenger train crashed through a bridge weakened by heavy rains, several deaths resulting; a week after that, 15 persons were killed when an Erie Railroad milk train crashed into the rear end of a passenger train near Binghamton, New York. In October more than 40 persons were killed near Paris, but the worst was yet to come — a Christmas Eve collision near Lagny, France, killed 191 persons, injured more than 300 others, and became the worst railroad disaster ever. A signal blurred by fog and mistaken by an engineer was believed responsible. AT THE END of the year, American newspaper editors pretty much agreed that 1933 was the biggest news year since The Great War, with a big story breaking almost every day. In responding to an Associated Press poll to name the top ten stories, the editors selected Franklin D. Roosevelt's recovery program as number one, mostly on the basis of its goals and how the President expanded the reach and the power of the federal government. The recovery program did not achieve its goals, but the way it was implemented had far-reaching effects and re-shaped our government. Roosevelt's opponents accused him of being a socialist dictator. Hearst columnist Arthur Brisbane considered this the biggest story of the year: |

|

|

|

The other nine stories on the Associated Press top ten list of big stories: Hitler's rise to power; repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment; recognition of the Soviet Union; the American bank holiday that shut down banks for awhile in order to stabilize them. Number six was the attempted assassination of Roosevelt; the destruction of the United States dirigible, the Akron; the California earthquake; the government's war on kidnappings, and the death of former President Coolidge. I'm not sure about a couple of those, nor do I agree with what those editors said a year later, that 1934 was even newsier. The arrest of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and the assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia would be the AP picks as the two biggest stories of '34. But they pale by comparison with the impact of 1933's top two stories. And number three — the repeal of Prohibition — affected the nation more than perhaps most people were willing to admit. For more varied look at an incredble year, check the following categories: |

|

| HOME • CONTACT | |