|

In a way their overseas flying adventure resembled the fable about the tortoise and the hare. Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh, the world's most famous flier, and his wife, the former Anne Morrow, a year removed from the tragic kidnapping and murder of their first child, set out on in July on a five-month trip that took them almost 30,000 miles to four continents and 31 countries.

Earlier in the year, the Lindberghs had hopped across the country and back, doing it in relatively short hops over a four-week period.

Many other fliers were engaged in tests of speed and distance. Several met success, others failed and paid the ultimate price. The Lindberghs covered much more distance, but did so at a pace that kept them in the news daily for most of the year.

There was a stated purpose to each trip — in April, Colonel Lindbergh was working on behalf of the Transcontinental and Western Air Company (later TWA) and on the much longer trip he was investigating and charting routes and potential landing sites for Pan-American Airways, of which he was an advisor as well as a company official. Whether he and his wife also were on a government mission is highly unlikely.

Though Lindbergh is flashing a big, almost silly grin in the above photo, he was aloof and secretive throughout the five-month journey. Meanwhile, his wife, who was open and engaging throughout, received an increasing amount of attention as weeks went by.

LINDBERGH may have been surprised and often irritated by the interest he and his wife generated, and by the large turnouts they attracted in almost every country they visited. An exception was the Soviet Union where many ordinary citizens didn't know who Lindbergh was. Soviet officials, however, treated the Lindberghs like visiting royalty. The obvious Russian agenda was to score points with the United States, which had yet to recognize the Soviet government.

Lindbergh's desire for privacy, something that would later prompt him to temporarily move to Europe, was all-too-apparent during this extended trip. Hanging over the Lindberghs throughout their travels was something that was little mentioned in newspaper articles I found. That is, there was another Lindbergh baby, son Jon, who was only 11 months old when his parents took to the air, leaving the toddler in the care of his nanny and the boy's grandmothers.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, who later would make her mark as an author ("Gift From the Sea" is her best-known work), operated the radio throughout 1933's five-month odyssey. She was praised for her reports, often delivered at 15-minute intervals, which kept people on the ground abreast of each flight.

HER CHEERY disposition and winning smile offset her husband's unwillingness to answer reporters' questions or even to indicate where they were headed on their next hop or when they were leaving. It also helped that Anne Morrow Lindbergh was as attractive and she was engaging. Few people have ever looked so good in a 1930s aviator's outfit. (That statement would surprise her; she apparently considered herself an ugly duckling compared with her two sisters.)

Lindbergh's skill and his careful attention to detail resulted in what seemed, in retrospect, a rather routine adventure, one largely forgotten when people recall his life and the history of aviation. But while other aviators briefly grabbed headlines during the year, it was the "Lindys," as the press referred to Mr. and Mrs. Lindbergh, who remained in the spotlight day after day from July 7 until December 20.

(Anne Morrow Lindbergh's second book, "Listen! The Wind," published in 1938, dealt with a 10-day period during the 1933 journey. Her first book, "North to the Orient," was based on a 1931 trip she and her husband took to China and Japan.)

IN THE SPRING of 1933, the Lindberghs spent a month flying from the East Coast to the West Coast and back again. This trip produced the most suspenseful flight of the year for the Lindberghs; well, at least, it seemed that way because of the way it was reported.

When they dropped out of sight and failed to reach one of their destinations, there was speculation they may have crashed. Turned out Lindbergh landed the plane during a sandstorm; he and his wife spent the night in their plane, in the middle of nowhere, and resumed their journey the next morning. To the pilot, the whole thing was no big deal; he was merely doing what common sense dictated.

Lindbergh's star would fall as the years went by and the world was shattered by war. The flying hero became one of the most reviled men in America, a Nazi sympathizer who thought Europe might be better off under the thumb of Adolf Hitler, a man he admired. Lindbergh was a spokesman for a group called America First, a tool of the Nazi party.

But in 1933 Charles A. Lindbergh could do little wrong, though people had begun to suspect he wasn't shy so much as he was aloof, insensitive and uncaring. More than once during his hops to four continents and 31 countries his unwillingness to disclose his whereabouts caused undue concern over his safety, with other men put at risk in efforts to find a plane that actually wasn't lost.

|

|

| |

Act one: going cross-country

Wednesday, April 19: Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh and Mrs. Lindbergh take off from Newark, New Jersey, in a Lockheed-Vega plane for the first leg of an inspection flight over the lines of the Transcontinental and Western Air Company. They fly to Baltimore and are overnight guests of Mrs. Louise Thaden, co-holder of the women’s endurance flight record.

Thursday, April 20: Colonel Lindbergh lands at Washington, D. C. airport. The colonel and his wife leave the capital in the afternoon in drizzling rain. They fly to Pittsburgh making what is intended as a brief stop before flying to Columbus, Ohio. However, an attendant at the Pittsburgh airport mistakenly places five gallons of water in the gasoline tank.

Lindbergh realizes the mistake soon after he takes off at 6 p.m. About 200 feet in the air, he says later, the motor of the plane went dead and he turned about, making a “dead stick” landing.

Taking off at 9 p.m., he again is forced to return to the Pittsburgh airport when he discovers there are no landing flares in his plane to be used in the event of a forced landing. Lindbergh finally leaves Pittsburgh at 9:45 p.m.

Friday, April 21: The Lindberghs land in Indianapolis after a 12-hour stay in Columbus, Ohio.

Sunday, April 23: The Lindberghs remain in St. Louis overnight and resume their transcontinental air tour Monday morning, flying to Kansas City. Lindbergh makes an informal visit to the National Guard headquarters at Lambert-St. Louis Flying Field where he was stationed during his days as an airmail pilot.

Thursday, April 27: The Lindberghs hop from Tulsa, Oklahoma, to Oklahoma City to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Winslow, Arizona. After refueling in Winslow, they take off at 6:15 p.m. for Los Angeles, but bad weather convinces Lindbergh to land in Kingman, Arizona, where he and his wife spend the night.

Friday, April 28: The Lindberghs reach Los Angeles, where they will remain several days while he inspects new flying equipment of the Transcontinental and Western Air Company.

Saturday, May 6: His inspections finished, Lindbergh begins his return trip eastward. He is expected next week in Washington, D. C. to testify in the trial of Gaston B. Means and N. T. Whitaker, charged with a conspiracy to steal $35,000 from Mrs. Evelyn Walsh MacLean as an aftermath of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping

There is concern for the Lindberghs when they do not arrive in Amarillo, Texas, as expected. They were last reported in Albuquerque in mid-afternoon.

Sunday, May 7: Colonel and Mrs. Lindbergh land in Columbus, Ohio. Field officials fail to hear the plane approaching and the Lindberghs are forced to land “blind” without the aid of flood lights.

Earlier the Lindberghs made a stop in Kansas City, where they told reporters they had slept soundly Saturday night in their big monoplane, grounded “somewhere in the Texas Panhandle” by a sandstorm.

“We spent a very comfortable night,” said Mrs. Lindbergh when the pair arrived at Kansas City, hours overdue.

Several airmen had set out in search of the missing couple. Colonel and Mrs. Lindbergh had taken off from Glendale, California, Saturday, and were forced down by the storm two hours after leaving Albuquerque.

“I’m sorry, but people shouldn’t worry,” said Colonel Lindbergh. “It’s liable to happen any time in the western country. It’s better to sit down when there are sandstorms. It’s too dangerous to go through them.”

Monday, May 8: Lindbergh sets his low-winged monoplane down in a difficult landing at Hoover Field in Washington just before dusk after a flight under stormy skies from Columbus, Ohio. A stiff crosswind blows across the airport, necessitating the use of the airport's shortest runway. Lindbergh's plane usually uses the longest runways available, but the flier makes what observers call a perfect landing.

Tuesday, May 9: Special police guards are detailed to the district supreme court in Washington, D. C., where Lindbergh is called as a witness in the conspiracy trial of Gaston B. Means, former department of justice associate, and Norman T. Whitaker. Hundreds of spectators throng the corridors.

Means already is serving a 15-year sentence for swindling Mrs. Evelyn Walsh McLean of $104,000 by representing he had contacted the kidnappers of the Lindbergh first born.

Whitaker has been identified as “The Fox,” one of the members of the kidnap gang as portrayed by Means in his stories that duped the Washington society woman. The government charges Whitaker told Mrs. McLean he had just held the Lindbergh child in his arms, even while its dead body lay in the New Jersey woodside near the Lindbergh estate.

The government charges that Mrs. McLean was about to pawn jewels to obtain $25,000 to give Whitaker in exchange for $49,000 “hot” money paid the kidnappers by a representative of the Lindberghs.

Lindbergh testifies to significant episodes concerning the abduction and death of his child in a proceeding that continues for the rest of the week. The Lindberghs remain in Washington where the trial reviews, in painful detail, the kidnapping and death of Charles A. Lindbergh Jr.

Wednesday, May 17: Means and Whitaker are found guilty of a conspiracy charge for which the maximum sentence is two years. |

|

|

Act two: She thought it would never end

The second trip, to Greenland and far beyond, was not expected to keep the Lindberghs away from the United States until December. The stated purpose was for Colonel Lindbergh to survey the North Atlantic on behalf of Pan-American Airways which hoped to use a northern route for service to and from Europe.

On Wednesday, June 28, two weeks before the Lindberghs departed from New York, their base ship, the Jelling, sailed from Philadelphia for Greenland, carrying an extra plane, 40,000 gallons of gasoline and provisions for three months. Col. and Mrs. Lindbergh would fly to Greenland and meet the Jelling in Holsteinborg.

Using a seaplane for this journey, Colonel and Mrs. Lindbergh lifted off July 10 from the East River at the Glenn H. Curtiss Airport in Queens. Weather conditions forced them to land in South Warren, Maine, just short of their goal at nearby North Haven, where their infant son, Jon, was staying with his two grandmothers.

|

| |

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 10

Colonel and Mrs. Charles A. Lindbergh, who today were at Rockland, Maine, preparing to continue their flight to Greenland, have flown many thousands of miles together and have gone through a long series of adventures in the air.

Mrs. Lindbergh, daughter of the late Senator Dwight W. Morrow and Mrs. Morrow, is both a licensed pilot and a wireless operator and considered an invaluable flight companion by her husband. She was chosen to accompany him on the present survey to the North, Colonel Lindbergh has let it be known, because he considers her better qualified than anyone else who might have been picked.

The Lindberghs flew together across the Pacific to Japan and China in 1931, across the American continent and made numerous shorter flights. Their earliest flying misadventure dates back to the courting days in Mexico, when a landing wheel dropped off the plane in which they were cruising over Valbuena Field. The Lindberghs landed safely, although the plane turned over on striking the ground.

They were both in a plane on the ground at Baltimore in December, 1930, when a burst of flame shot from the engine. Calmly Mrs. Lindbergh, seated in the cockpit, shut off the ignition and the gasoline supply, thus preventing a possible explosion. The Colonel, meanwhile, seized an extinguisher and put out the flames.

On their flight to the Orient, they were spilled from their plane into the Yangtze River, but later laughed about the mishap, the Associated Press reported, and denied they were ever in danger. On that flight they went through a slight earthquake in Japan, later describing “a rather odd, queer sensation” at the time.

They outflew a typhoon and worked for the relief of sufferers from the great floods. Once a starving mob rushed them for food and, when the danger to the plane became too great, forced them to escape by flight.

In April, 1930, they crossed the American continent in 14 hours, 23 minutes and 27 seconds, then a record. |

|

| |

The Lindberghs hopped their way to Greenland, spending time in Halifax, Nova Scotia; St. John's, Newfoundland; Botwood, Newfoundland; Cartwright, Labrador, and Hopedale, Labrador. There were delays along the way, and at least one of the stops — in Hopedale — was unplanned and caused by adverse weather.

On July 22 the Lindys landed in Godthaab, Greenland, where a large crowd gathered at the water's edge to greet them. On July 26 they landed in Holsteinborg, Greenland, beating their supply ship, Jelling, by a few hours.

The Lindberghs spent a month in Greenland, surveying the coastline. Colonel Lindbergh, who shared little information with reporters, did admit that a flight to Baffin Land and back was perilous. He revealed he had been unable to land because of ice and fog, and that much of the distance he had flown blind.

Credit is given Colonel and Mrs. Lindbergh for discovering a previously unrecorded mountain and an uncharted fjord in Greenland. They reported their findings to officials of the Pan-American Airways, Inc., who made known their discoveries.

The Lindberghs also spotted a herd of muskoxen and polar bears in an inland section from Scoresbey Sun, where herds were believed to be extinct.

WHEN THE COUPLE finally departed Greenland, they flew to Reykjavik, Iceland. From there they stopped at the Faroe Islands, the Shetland Islands and Copenhagen, Denmark, where "Lindbergh cakes" and "Lindbergh puddings" were sold in restaurants and cafes.

From Denmark, the Americans visited the Swedish home of Lindbergh's ancestors before flying to Stockholm. Lindbergh, as was his habit throughout the trip, asked for as much privacy as possible. All official receptions were banned.

At Stockholm's Barkarby air field, Lindbergh impressed military experts with his prowess when he flew a new type of airplane with which he was unfamiliar. It was a controversial plane because a similar machine had recently crashed, killing three persons.

On September 20, the Lindberghs arrived in Finland. Two days later they went to Leningrad in Soviet Russia, one of the few places where Lindbergh was virtually unknown to the public. Russian officials, however, gave special treatment to the Lindberghs, hoping to favorably influence President Franklin D. Roosevelt back in Washington. At that point the Soviet government had not yet been recognized by the United States.

From Leningrad, the Lindberghs went to Moscow, then Tallin, Estonia, and Oslo, Norway. From Oslo, they hopped to Stavanger, Norway, then to the Woolston seaplane airport near Southampton on October 4. By now Colonel Lindbergh had become known as "the American sphinx" for his refusal to talk. After almost three weeks in England, the Lindberghs flew to Galway, Irish Free State. There Anne Morrow Lindbergh briefly talked to a reporter and admitted the trip was taking a toll.

|

| |

New York Evening Post, October 24

GALWAY, Irish Free State (AP) — Mrs. Charles A. Lindbergh is getting homesick.

“I’m terribly anxious to see my baby,” said the wife of the famous American airman after their hop from Southampton, England. “Yes, I’ll be glad to be back home again.”

She insisted, however, the long trip with her husband has not been tiresome and she said she considered Ireland one of the most delightful lands over which they have flown.

But perhaps there was a reason:

The westerly part of Ireland, Colonel Lindbergh pointed out to his wife, gave him his first sight of land after his historic lone Atlantic crossing.

Even the quiet-mannered Colonel confessed seeing the land again gave him a “thrill of pleasure.”

Colonel and Mrs. Lindbergh will fly to Scotland after their aerial survey of the northern coast of Ireland.

Their plans for a takeoff today on a morning flight up the coast to Londonderry temporarily were delayed.

It developed later that Colonel Lindbergh had given up the plan of flying today, but he and Mrs. Lindbergh intend to fly to Inverness, Scotland, tomorrow. |

|

| |

On October 26, the Lindberghs took off from Inverness without revealing their destination. Many people thought they were going back to England, but late that afternoon they touched down on the River Seine, near Paris. This was a pleasant surprise for the French, perhaps, but it was an example of how Lindbergh did not understand or appreciate that his secrecy was inconveniencing others, even putting them at risk.

The presence of the Lindberghs in Paris wasn't made public until the next morning. By then, concerned British officials had launched a search party for the Americans who were feared lost.

In Paris, Mrs. Lindbergh opened her hotel room to an American reporter and again said how anxious she was to return home to her young son. This interview would lead to speculation the Lindys had just about wrapped up their trip and would sail back to the United States. Newspapers that said as much would be proven wrong . . . and Mrs. Lindbergh's wishes would not be granted by her husband, who had other ideas.

|

| |

New York Sun, October 27, 1933

By MARY KNIGHT

United Press

PARIS — “We’re going home soon, and we’re not flying — once is enough.” So said Mrs. Charles A Lindbergh today as she sat wistfully in her apartment at the Crillon Hotel, almost a prisoner of surging crowds waiting outside to cheer her and her famous husband.

The attractive wife of the world’s most famous flier is homesick, frankly and thoroughly. For this reason, she is eager to leave this European capital, where her husband won world fame. She can’t even buy Paris gowns because Col. Lindbergh points out that they have no room for more baggage.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh and the Colonel were almost fugitives today from the acclaim that has followed them from here to China. In their usual shy manner, they arrived in utmost secrecy last night from Inverness, Scotland, buffeted by a Channel storm. They hid themselves in the Crillon, hoping to avoid the crowds.

The United Press correspondent climbed the backstairs of the hotel and dodged a skirmish line of hotel detectives to reach the two-room Lindbergh apartment in the hotel, headquarters for international conferences that have changed world maps.

Mrs. Lindbergh, it was revealed at once, longs for home and housekeeping, and has reconciled herself to forgoing the Paris frocks on which she had set her heart.

Most of her worries concern her sister, Mrs. Aubrey Neil Morgan, the former Elisabeth Morrow, who recently sailed for the United States to undergo treatment.

Expressing worry over her sister’s health, Mrs. Lindbergh said, “The climate of Wales, where she makes her home, isn’t best for her, so she is on her way to southern California.”

Mrs. Lindbergh was in her bedroom, smartly dressed in brown with no makeup. It was her first visit to Paris in nine years and it had turned into an ordeal. She expected to leave this weekend, she said.

“We are not going to fly the Atlantic homeward, but we are sailing very soon. We are not going home that way again — once is enough.”

I was pleasantly surprised to find Mrs. Lindbergh, a lonesome girl, alone and glad to talk to another American girl. Arriving at the fortress-like hotel at the unusual visiting hour of 9 a.m., I had waited until Lindbergh left by a side door before rapping.

“I’ll be glad to help you shop,” I said as I talked to Mrs. Lindbergh.

“There’s nothing I’d rather do than to buy a couple of dresses,” she replied, “but Charles says there is no room for more baggage. We must travel light, you know. If I shipped dresses home, the customs duty probably would be severe — so I must go without, although I haven’t seen Paris in nine years.”

Asked whether she preferred life as a flier’s wife to that of a housekeeping one, Mrs. Lindbergh said:

“I do both. It’s an ideal life. I like to make such trips as this. Sometimes it’s more exciting than housekeeping, but I enjoy housework very much.

“I’ll be glad to get back. I have heard the latest news of Baby (Jon Lindbergh). He is well. Mother is always glad when I go and leave the baby with her.

“I still get a thrill out of flying,” she said. “I remember how excited I was when Amelia Earhart succeeded in making the first solo Atlantic flight by a woman.

“I have piloted our seaplane occasionally on our present flight. Yesterday’s flight was partly rocky, but not uncomfortable, although I understand some people feared for our safety.”

Airport officials all over Great Britain, Ireland and France watched all night for the couple, not knowing their destination.

Missing for many hours in a storm that raged along the British and French coasts, Col. Lindbergh and his wife landed secretly at the naval seaplane testing station and went unobserved to the Crillon Hotel.

While they slept, airport attaches all over Great Britain and France watched anxiously for them. They awoke today to find thousands of Parisians, deserting their jobs, massed outside their hotel in the historic Concorde Square where Louis XVI was guillotined.

Dismayed, the Lindberghs at once changed to a room facing on a side street.

Mrs. Lindbergh lunched quietly at the hotel with a party of friends. Col. Lindbergh, who had left the hotel with Pierre Cot, French Air Minister, went to the naval seaplane testing station at Les Mureaux, on the Seine, near Paris, to work on his plane.

Col. Lindbergh’s greeting to Paris on his first return since 1927 came today through the American embassy which issued this statement “in the name of Col. Lindbergh:”

“Mr. Lindbergh states that he is happy to return to Paris after six years, and that he is looking forward to a few quiet days. There is no official significance in his presence, and he has no immediate plans either for the date of his departure or for his destination.”

After luncheon, Col. Lindbergh met about fifty reporters from Paris newspapers, and a large group of foreign correspondents, shaking hands with each one. He refused, however, to give any interviews, or to speak on any subject whatsoever.

For fifteen minutes, the Colonel spoke in private with Ernest Hemingway, the author, after which he went on an inspection tour of the new embassy.

Col. Lindbergh indicated he intends to remain in Paris until Tuesday. During the day he talked by telephone with some of the leading French airplane builders.

There was no doubt that to Paris, Lindbergh is still the idol of 1927, when he landed at Le Bourget Field after a solo flight from New York.

It was stated that Col. Lindbergh, who carried letter of introduction on his first visit, wished he needed them today.

His fight against being lionized was to be a hard one. The War Ministry announced it would ask him to agree to a program of entertainment, he to decide on its extent. |

|

| |

The Lindberghs remained in France a few days, then resumed their hopping — to Amsterdam, The Netherlands to Geneva, Switzerland, then Santona, Spain, an unexpected stop made necessary by fog during an attempt to reach Lisbon, Portugal. Jose Albo, a Santona businessman, invited the Lindberghs to stay at his home. Albo introduced his guests to his nephew, the only person in Santona who spoke English.

Charles Lindbergh loved to fly. To him it was the only way to travel. There'd be no ocean voyage home for his wife. A second attempt to reach Lisbon was frustrated by the weather, forcing Lindbergh to land on the Minho River between Spain and Portugal, near the summer resort of Caldelas De Guy. Finally, on November 15, the Lindberghs flew to Lisbon where they were given a welcome befitting two of the most famous people in the world.

From there, the Lindberghs flew to the Azores, the Canary Islands, Cape Verde and the Gambia River in Bathurst (Banjul), on the west coast of Africa. They arrived in Bathurst on November 30, which, in 1933, was Thanksgiving Day in the United States.

They were delayed in Bathurst, but when they finally departed they headed toward Brazil in a flight that put Mrs. Lindbergh in the spotlight.

|

| |

Schenectady Gazette, December 7

NATAL, Brazil (AP) — Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh and his wireless-operating wife, the former Anne Morrow, alighted on the harbor yesterday (December 6) at 3:10 p.m. Brazilian time (1:10 p.m., EST) after flying from Bathurst, Gambia, Africa, 1,875 miles away in 16 hours, 10 minutes.

It was their first view of America since July 22 when they took off from Cartwright, Labrador, for Greenland on a survey flight across the north Atlantic.

The whole population of Natal, its stores and offices closed for the fiesta of welcome, its streets decorated, packed the waterfront.

At 2:50 p.m., a keen-eyed watcher caught the first glimpse of the great red monoplane as it headed in from the Atlantic. Launch whistles blared and from the crowd arose a mighty roar of “Viva!”

Straight in toward the harbor the plane flew, and passed above the cheering throng. Lindbergh banked it gracefully over the town and set it down smoothly in the harbor.

With the alighting of the ship, Mrs. Lindbergh became the first woman ever to fly in an airplane across the south Atlantic.

A welcomer called her attention to the fact and Mrs. Lindbergh replied, “I hope not to be the last.”

The Americans said they were too tired to partake of the festivities which the generous Brazilians had planned for them. Instead they went in an automobile directly from the docks to the home of the English consul, A. D. Scotchbrook, who was one of the first to greet them when their plane was put at anchor.

When they came ashore, both the fliers wore their air outfits. Mrs. Lindbergh wore breeches; the colonel was in shirt sleeves and wore a wide-brimmed hat.

He told the Associated Press he would inspect his plane today and decide then on a date of departure from Natal.

The South Atlantic flight, as was the previous flight across the North Atlantic, was part of the survey work the Lindberghs are carrying on for Pan-American Airways, for which the colonel is technical adviser. The 75 wireless stations of the American International Air Line, which direct its passenger and mail planes on their South American flights, kept a close watch for signals from the Lindbergh plane.

At the wireless instrument, keeping in close communication with Rio de Janeiro through the long flight, sat Mrs. Lindbergh. The skill with which she operated the key was commented on by the veteran experts who listened in on her signals.

She made her reports at regular intervals and by them the waiting aviation technicians were able to chart a course for the plane which they said varied only slightly from a straight line between the taking-off and alighting points.

Mrs. Lindbergh made a great impression on the women of Natal. They admired her cheerfulness and composure and were voluble in their praise of her courage. They were particularly impressed by her constant vigilance at the radio during the long flight from Bathurst. |

|

| |

Act three: Home at last

The Lindberghs were invited to visit other Brazil cities, including Rio de Janeiro, but this time Mrs. Lindbergh would not be denied. She wanted to be home before Christmas.

Two days after they had arrived in Natal, the Lindberghs flew 1,100 miles northwest to Para, Brazil. From there they hopped 920 miles up the Amazon to Manaos, an outpost in the Brazilian jungle.

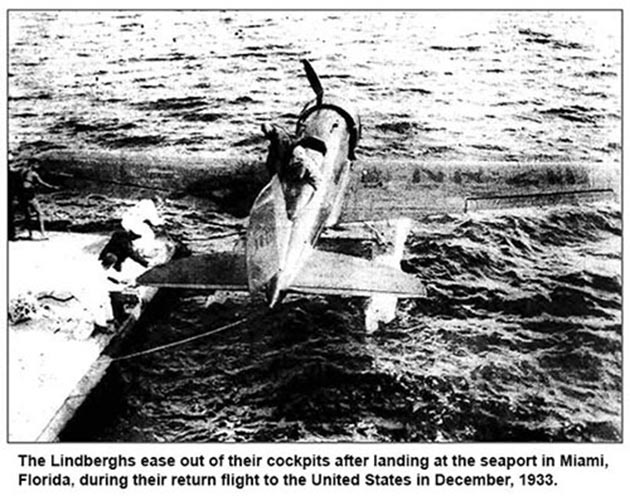

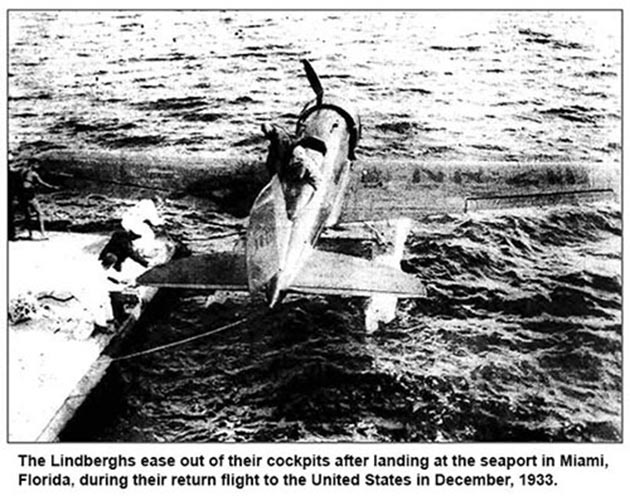

From Manaos, Lindbergh charted perhaps his most dangerous flight — 700 miles over mostly uninhabited wilderness in the most direct route to Trinidad. Next came stops in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republic; then Miami, Florida; Charleston, South Carolina, and, at last, New York.

|

| |

Cortland Standard, December 20

NEW YORK (AP) — Colonel and Mrs. Charles A. Lindbergh brought their 30,000-mile, two-way Atlantic air odyssey to an end yesterday on the waters of the East River from which they had started on their flying adventure five months and 10 days earlier.

They alighted at 2:40 p.m., five hours and 45 minutes after their takeoff from Charleston, South Carolina, on the final 660-mile leg of their homeward flight.

Last night the Lindberghs were reunited with their baby son, Jon, at the Englewood, New Jersey, home of Mrs. Lindbergh’s mother, Mrs. Dwight W. Morrow. Mrs. Evangeline Lodge Lindbergh, widowed mother of the aviator, also was on hand.

So unexpected was the arrival at College Point, across Flushing Bay from the Glenn Curtis airport, that only a few were present to greet the Lindberghs, which was just what the flying colonel wanted. Very soon, however, a crowd collected, but Colonel Lindbergh would say nothing about his flight.

On their journey, Colonel and Mrs. Charles A. Lindbergh bounded an area equivalent to more than a quarter of the world, flew about 29,081 miles over land and water. They spent about 198 hours in the air, and part of this will be credited officially to Mrs. Lindbergh to make her eligible for a transport pilot’s license.

The Lindberghs have seen the frozen north, the broiling tropics, the somberness of the Scandinavian capitals and the glamor of the European world. They have played all manner of parts, from efficient engineering research workers on the survey and goodwill ambassadors to obscure tourists when they could evade the crowds, adventurous campers when they were in the north, and uninvited but welcome guests when they were forced to land short of their daily goals by bad weather where no preparations had been made for them.

Now the Lindberghs have to do is get ready for Christmas. They brought little back with them when they ended their flight yesterday. In fact, all they carried off their plane were two knapsacks of personal effects they had with them on the last 10,000 miles of the trip. So there will have to be some hurried gift buying and other preparations for Christmas. |

|

| |

| HOME • CONTACT |

| |

|