OUR STAY in Los Angeles was entertainment oriented. No surprise. It's not like we went there for a museum tour. Instead we attended an Emmy Awards party for the nominees, giving us an opportunity to mingle with a few celebrities, including singer Andy Williams. (See My Huckleberry Friend.)

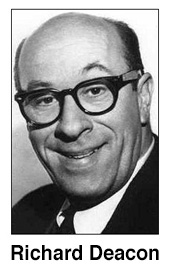

Also there was Richard Deacon, who played Mel Cooley on "The Dick Van Dyke Show." He was the only member of the show in town that week, which is why he attended. He apparently thought Lynn and I were a lovers because  during our conversation he invited us to another party, mentioning that one of the guests would be Rock Hudson. He also invited us to his Beverly Hills home. Lynn and I picked up on Deacon's vibe and he soon realized we actually were two heterosexuals hoping to meet starlets.

during our conversation he invited us to another party, mentioning that one of the guests would be Rock Hudson. He also invited us to his Beverly Hills home. Lynn and I picked up on Deacon's vibe and he soon realized we actually were two heterosexuals hoping to meet starlets.

There was no harm done — and I did appreciate him spilling the beans about Rock Hudson — and two weeks later I interviewed him at his Beverly Hills home, which was neatly tucked against some huge rocks near the top of a steep, winding street. It was a great place to get away from it all. We had a nice talk about his career, especially his work on the "Van Dyke" show. He was from Binghamton, New York, and said that as soon as he heard my voice at the Emmy party he recognized the Central New York accent.

Deacon originally wanted to be a doctor and was working as an orderly in a Binghamton hospital when World War II broke out.

"I tried to join the Navy," he told me, "but they turned me down. The recruiter sent me across the street to the Army because he said the Army would take anyone. They did." He wound up in the Army's medical corps."

The actor reminded me a lot of a friend who went through basic training with me during our brief stint with the Army. (We were Reservists whose active duty was completed in six months.) My friend had attended parochial schools through 12th grade and had never had a physical education class. He was overweight and badly out of shape. Deacon was just as soft. Shaking his hand was like squeezing a bag of marshmallows.

After the war Deacon enrolled at Ithaca College, still hoping for a medical career, but was restless and found he had lost interest in being a student, so he moved to New York City and turned to acting. As is true with a lot of actors, Deacon supported himself by working as a bartender. His physical appearance, including his balding head, soon put him in demand as a character actor.

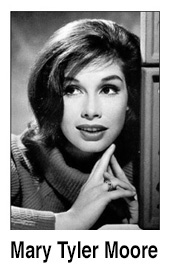

AT THE EMMY PARTY Lynn and I also met Irene Ryan, who had been nominated as best actress in a comedy series. (She correctly predicted Mary Tyler Moore would win, complaining just a bit that the industry had no respect for her series, "The Beverly Hillbillies.")

Ryan was surprisingly friendly and got along especially well with Lynn. She invited us to visit the set of her series, which was about to wrap up filming of its last episode of  the season. The sitcom was a Filmways Production, but I can't remember where it was shot. Anyway, a day or two later Lynn and I visited the set, had a brief chat with Ryan, then watched her film a scene — during which she was bitten by a chimpanzee, probably the one known on "The Beverly Hillbillies" as Cousin Bessie.

the season. The sitcom was a Filmways Production, but I can't remember where it was shot. Anyway, a day or two later Lynn and I visited the set, had a brief chat with Ryan, then watched her film a scene — during which she was bitten by a chimpanzee, probably the one known on "The Beverly Hillbillies" as Cousin Bessie.

Such incidents were not unusual for actors working with chimpanzees, and this one required that Ryan be taken to a hospital. As she was being driven away, she told her driver to stop. She rolled down a window, called Lynn and me over, and apologized for what had happened. It was an amazing gesture, though I had forgotten about it until I called Lynn recently to compare notes.

What I recalled more vividly was Buddy Ebsen's reaction to the chimp incident. He loved Irene Ryan and all that, but Ebsen was anxious to finish the season and begin his summer hiatus. Given his druthers, Ebsen probably would have strangled the animal.

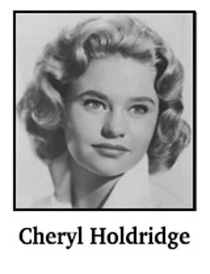

Lynn and I visited a couple of other studios, including Universal and MGM. At Universal I met Cheryl Holdridge and Allyson Ames, who back in those days were referred to as actresses, not actors. I still think actress is usually more appropriate; certainly it was in this case because these were two lovely ladies, who at this point in their lives seemed more concerned with their personal lives than their careers. We chatted awhile in a recording studio where they were dubbing lines for an episode of "Wagon Train," in which they were two of the guest stars.

Holdridge was the better known of the two, a former Mousketeer who also had made eight appearances as a child performer on "Leave It To Beaver." She was 20 years old and had moved on to guest roles in several prime time series. She was preoccupied with her romance with Lance Reventlow, son of Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton. Reventlow, usually described as a playboy, had recently divorced actress Jill St. John, a sore subject with Holdridge, who correctly predicted on the day we met that St. John no longer was in the picture; she and Reventlow would wed. Which they did six months later. Then she retired from acting, though she would briefly unretire in 1985 to make two TV appearances in "The New Leave It To Beaver." She also had a role in the 2000 movie, "The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas."

Holdridge was the better known of the two, a former Mousketeer who also had made eight appearances as a child performer on "Leave It To Beaver." She was 20 years old and had moved on to guest roles in several prime time series. She was preoccupied with her romance with Lance Reventlow, son of Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton. Reventlow, usually described as a playboy, had recently divorced actress Jill St. John, a sore subject with Holdridge, who correctly predicted on the day we met that St. John no longer was in the picture; she and Reventlow would wed. Which they did six months later. Then she retired from acting, though she would briefly unretire in 1985 to make two TV appearances in "The New Leave It To Beaver." She also had a role in the 2000 movie, "The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas."

Reventlow's full name was Lawrence Graf von Haugwitz-Hardenberg-Reventlow. He also was the stepson of Cary Grant and of another of his mother's husbands, Prince Igor Troubetzkoy, an auto racer. Reventlow had been a friend of James Dean, sharing the actor's love of fast cars. Reventlow, also a pilot, would be killed in 1972 in the crash of a small plane. Holdridge would marry twice after that. She died in 2009.

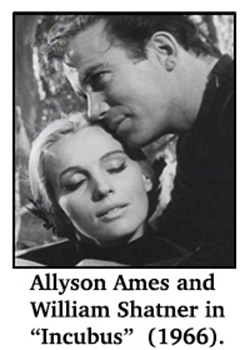

Ames was considered a better actress, but her career came to an end soon after she she married producer-director Leslie Stevens, who worked on such TV hits "Outer Limits," "The Name of the Game," "McCloud" and "The Virginian." He also wrote and directed a 1966 horror film, "Incubus," that starred Ames and William Shatner. By the time the film was released Ames and Stevens were headed for a divorce. Their marriage lasted about one year.

I haven't found any biography of Allyson Ames on-line, but my recollection is she had been married previously and in 1964 was a single mother with two or three children. I may have her confused with another Allyson (or Allison), but I don't think so. During our conversation she joked that if I wanted an interesting look at the glamorous life of a young actress I should stop by her apartment for dinner, which I took to be a reference to caring for and feeding her children. Holdridge egged me on, as though Ames was asking me out, but I figured I was being drawn into a joke, the punchline of which would be "Gotcha!" Besides, a Hollywood-based wire service writer, Bob Thomas, I think, had already done a story of the hard life of Allyson Ames (or an actress named Allison) who was raising children on her own while she waited for her big break.

I haven't found any biography of Allyson Ames on-line, but my recollection is she had been married previously and in 1964 was a single mother with two or three children. I may have her confused with another Allyson (or Allison), but I don't think so. During our conversation she joked that if I wanted an interesting look at the glamorous life of a young actress I should stop by her apartment for dinner, which I took to be a reference to caring for and feeding her children. Holdridge egged me on, as though Ames was asking me out, but I figured I was being drawn into a joke, the punchline of which would be "Gotcha!" Besides, a Hollywood-based wire service writer, Bob Thomas, I think, had already done a story of the hard life of Allyson Ames (or an actress named Allison) who was raising children on her own while she waited for her big break.

Our visit to MGM was far less interesting, though Lynn and I did visit a set where the movie "36 Hours" was being filmed. We saw Rod Taylor, Eva Marie Saint and James Garner, but I don't recall meeting them. I certainly would have enjoyed the opportunity to meet Garner, one of the all-time favorites, while my mother would have been thrilled if I had interviewed Taylor, one of her faves.

WHEN WE LEFT Los Angeles, Lynn and I made another dumb driving decision — we took an inside route north instead of driving the scenic Coast Highway, which would have been slower perhaps, but much prettier and about 20 degrees cooler. A week earlier we had encountered snow near Victorville; now, near Fresno, the temperature was in the low 90s.

However, it was cool and comfortable in the San Francisco area. When we dropped off the car in Oakland, the folks there weren't all that happy about the tire deal we had made in Oklahoma City, but were nice enough to arrange a ride for us from the dealership to downtown San Francisco where we were met by our Kent State friend, Kevin McTigue. (Every time I tell this story I have to explain that Lynn Kandel is a man, Kevin McTigue is a woman.)

Lynn and I stayed at Kevin's apartment. She was a Cleveland native, but had found work in San Francisco and became one of her adopted city's biggest cheerleaders. Her enthusiasm for the city wore on me a bit, so I told her what I liked about San Francisco is it reminded me a lot of Pittsburgh, a comment she didn't appreciate. (I was only half-kidding, because the Greater Pittsburgh Area includes several San Francisco-like hills. My favorite is Mount Washington, which, I believe, is still serviced by the Monongahela and Duquesne Inclines, notch railroads which transport people up and down the steep hill that overlooks the city at the point the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers meet to form the Ohio River.)

Kevin had to work the week we were there, but she let us use her car, advising us the brakes were soft, which made stopping an adventure at the bottom of those ski slopes that pass for streets in San Francisco.

I skipped out on Lynn and Kevin for a couple of days to accept an invitation from ABC to fly to Portland to watch how the network covered the Oregon presidential primary. The network's press department wasn't looking for coverage, simply a few bodies who'd wander around that night wearing badges announcing their newspaper affiliation.

Also accepting the invitation was writer Don Freeman of the San Diego Union-Tribune. We arrived in Portland the night before the primary. The next day ABC gave us a car and told us to do anything we wanted. We went for a drive through some beautiful wilderness along a river, probably the Columbia. At one point we saw a wildcat of some sort crossing the road. We also stopped to get a close look at a stream that tumbled down the wooded mountain, toward the river. I could understand how people fall in love with the Northwest.

We got back to Portland in time for dinner, then watched Howard K. Smith anchor the network coverage. At some point during our visit I interviewed Smith for a story I wrote when I returned to Akron.

I returned to San Francisco on Wednesday and a few days later Lynn flew home to Cleveland, I returned to Los Angeles and the Continental Hotel.

I returned to San Francisco on Wednesday and a few days later Lynn flew home to Cleveland, I returned to Los Angeles and the Continental Hotel.

That week I had lunch with Mary Tyler Moore and her then-husband Grant Tinker. A week later she would win an Emmy as best actress in a TV series, an honor that was deeply appreciated because she was still hurting from early reviews of "The Dick Van Dyke Show" which had called her the program's weak link.

In 1964 she had no idea she would achieve even greater success with her own show. She said at the time her goal was to star in the kind of movies that Doris Day made. She had a few big screen opportunities, but would discover how sweet success can be on the small screen.

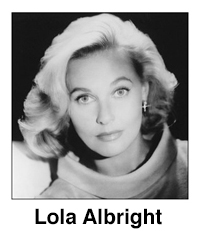

NUMBER ONE on my Must Interview list was Akron native Lola Albright, who had become a popular television star for her work on "Peter Gunn" (1958-61). She also appeared in several movies, including "Champion" (1949) and "The Tender Trap" (1955), though perhaps her biggest role was opposite Elvis Presley in "Kid Gallahad" (1962). A year earlier she had starred opposite Scott Marlowe, a very intense young actor in the James Dean mold, in "Cold Wind in August" about a 28-year-old stripper involved with a teenaged boy. It was a small, but controversial film which some thought should have earned Albright an Oscar nomination.

A few weeks prior to our meeting, Albright worked with Jane Fonda and Alain Delon in "Love Cage," a sordid tale that did nothing for the careers of those involved. "A big part of the  problem," said Albright, "was the script. It was written in French and translated for an American audience by a woman from London who wasn't familiar with American slang. Much of her translation had a double meaning."

problem," said Albright, "was the script. It was written in French and translated for an American audience by a woman from London who wasn't familiar with American slang. Much of her translation had a double meaning."

Our interview took place in a restaurant-bar run by her husband, Bill Chadney, whom she had met while working on "Peter Gunn." (He was the piano player in the jazz band that backed Albright, who played singer Edie Hart.)

At one point in the interview Albright told me her husband was eying me from behind the bar. "He's jealous," she said, smiling. "He's wondering who you are. I didn't tell him you were here to interview me." (Nothing happened, though the movie version would have Chadney confronting me, which would lead to a fight, which I would deliberately lose.)

My interview didn't prevent Albright from tending to restaurant business involving a ball-point pen and matchbook covers.

"My husband ordered 65,000 books of matches when he opened the restaurant six weeks ago. They're beautiful, aren't they? Expensive, too, thanks to this raised gold lettering. There's just one problem – they've all got the wrong telephone number."

So there we sat — me asking questions and Albright crossing out and correcting the telephone number.

TWO YEARS earlier, at an Ohio summer theater, I had interviewed Albright's first husband, Jack Carson, another of my favorite actors. He and Albright had divorced by then. It was his third marriage and lasted from 1952-58. (Albright and Chadney would divorce in 1975.)

Albright was working as a radio station receptionist in Cleveland when a talent agent spotted her and arranged an interview with scouts from MGM.

"I've never figured out how I got the contract," she said. "I was terrible. Absolutely terrible. It didn't bother me that I was terrible. The important thing was the contract.

"I wanted to be a good actress who worked a little, but I wasn't really interested in learning how to act. As a result, I was a bad actress who worked a little."

When she married Carson, she lost interest in acting. "I never really wanted to work again until that marriage broke up. After our divorce I took stock of myself and discovered acting was the only field open to me."

Finally, she set out to become a good actress and even took singing lessons, which prepared her for "Peter Gunn." She did her own singing on the show, even made an album or two. (A cable television station has been showing reruns of "Peter Gunn," and I'm pleased to report that Lola Albright, as Edie Hart, remains one of the television's sexiest characters. It's a program with ridiculous plots, but good music, great dialogue and the coolest private eye hero of them all.)

Going from the sublime to the ridiculous ... another interview that week prompted me to write a story that began like this:

The name on the office door said George Burns, but the man inside looked more like J. Fred Muggs. He sat low behind a desk that was several sizes too large ... and wore an old Ben Hogan-style golf cap that likewise was too large.

As expected, there was a big cigar in his mouth that blocked almost as much of his face as the cap. He removed the cigar only when he spoke – and then used the cigar as a pointer, waving or thrusting it in all directions to emphasize his words. His chain-smoking had given the office an odor that would make even downtown Akron seem like a fresh air camp.

His sport-shirt and trousers were loud, even by California's zany standards, but they obviously made him feel comfortable. He had on thick-rimmed glasses (the better to see through the cigar smoke, my dear) and the lines on his face made him look every one of his 68 years. Maybe older.

Burns was in the first stages of his career without his wife and partner, Gracie Allen, who had retired in 1958, for health reasons.

"The way I look at it," he told me, "I've only been working since Gracie retired. When we were a team she did all the work. I'd start a routine by asking, 'How's your uncle?' Then she'd talk for 17 minutes. It was great."

Our interview was to promote "Wendy and Me," a situation comedy he had created. His co-star was Connie Stevens. (Gracie Allen would die about a month before this show went on the air.)

"Wendy and Me" lasted only one season, but eventually Burns achieved tremendous success in the movies, winning an Oscar for best supporting actor in 1975's "The Sunshine Boys" (after he replaced Jack Benny, who was too ill to do the film and soon died). Burns also had a big hit movie in "Oh, God" (1977) and followed it with two sequels. He would die in 1996 at the age of 100.

ANOTHER NEW sitcom that failed in the fall of 1964 was "Mickey," starring Mickey Rooney. I met Rooney during my California visit, but didn't interview him. His program also featured his son Tim. And while the show lasted only one season, it did earn Rooney a Golden Globe as the best actor in a TV series.

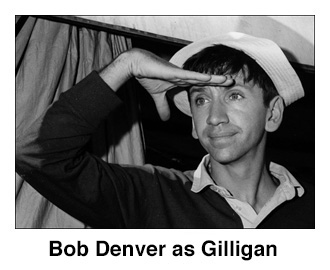

Having better success with a new series was Bob Denver, with whom I had dinner one night. Well, Denver and his wife were among the folks at the table. Our conversation produced no story. At the time Denver was best known for playing Maynard G. Krebs  on "The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis." That would change in September when "Gilligan's Island" premiered. At the time of our meeting Denver looked as though he had fallen on tough times, which apparently was the case, as he would explain to me a year later in a telephone interview.

on "The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis." That would change in September when "Gilligan's Island" premiered. At the time of our meeting Denver looked as though he had fallen on tough times, which apparently was the case, as he would explain to me a year later in a telephone interview.

Turned out a series of delays kept "Gilligan's Island" from filming until August, a couple of months later than planned. Denver said things were so bad he was borrowing money to feed his wife and three children.

"Here I was, the star of a new television show and I was practically starving."

A few months later he and his family were living comfortably and eating well.

I DON'T RECALL who gave it to me – it might have been Richard Deacon, who had a role in the film – but at some time during my California visit I acquired a copy of the script for the movie, "John Goldfarb, Please Come Home." Several people I met in Los Angeles had high hopes for this comedy, which was based on a book by William Peter Blatty, who later would write "The Exorcist."

"Goldfarb" was a spoof about an American U2 pilot (and a football player famous for once running the wrong way) who crashes in the Arab country of Fawzia which is ruled by a king obsessed with putting together a football team that can beat Notre Dame. Richard Crenna starred as the pilot, Peter Ustinov as the king, with Shirley MacLaine playing an American magazine writer who goes undercover in the king's harem. The plot has Ustinov threatening to turn Crenna over to the Russians unless Crenna agrees to coach the Fawzia football team.

The script seemed funny enough, but, then, I had never read a movie script before. The comedy was a bit overdone but typical of the times, starting with the names of the characters, including Heinous Overreach (head of the CIA), Charles Maginot (secretary of defense), Stottle Cronkite (head of the United State Information Agency), Miles Whitepaper (a U.S. government official) and Sakalakis (the Notre Dame coach). MacLaine's magazine was called Strife.

"John Goldfarb, Please Come Home" turned out to be one of the worst films of the 1960s. Ustinov, a notorious scenery chewer, outdid himself. Deacon had mentioned the film during our interview — he played Charles Maginot — and claimed Ustinov's double talk as the Fawzia king inadvertently produced words some Arabs found offensive. Meanwhile, the most offended party was Notre Dame University. The school's defamation suit delayed the opening of the film, which would become a trivia lover's delight. It's not worth sitting through, but if you are truly desperate then see if you can spot Jerry Orbach, Teri Garr, Telly Savalas and James Brolin. (Hint: the unbilled Brolin plays the Notre Dame quarterback.)

I also met an agent who predicted super stardom for an actress named Anjanette Comer, a Suzanne Pleshette lookalike who was featured in two other films that would bomb at the box office — "Quick, Before It Melts" with George Maharis and Robert Morse and "The Loved One" (1965) with Morse, Jonathan Winters, James Coburn, Rod Steiger and Liberace.

And another agent cornered me to say he represented an actor who would be very, very big — Andrew Prine, whom he described as “Tony Perkins with balls.” (In all fairness to Prine, he is an excellent and interesting actor, but one who was always better suited to supporting roles.)

AND SO I bid California a fond adieu — as they used to say in 1950s movie travelogues presented between the Coming Attractions and the Featured Film. My flight to Cleveland was uneventful, though I wouldn't be surprised if one of the stewardesses (as they used to be called) still has bruises from the squirming gentleman in an aisle seat who kept sticking out his elbow, punching her hip as she walked by. That seat squirmer would be me.

Lynn Kandel, now a resident of Indianapolis, reminded me of a newspaper article by a Los Angeles columnist who had attended the Emmy party and noticed the two young men from Ohio. His article mentioned the public relations man from a Cleveland hospital. "I have no idea what he was doing at this party," said the columnist, "but he looked like he was having lots of fun."

Well, both of us had lots of fun. So much fun that a year later we took another road trip, in my '65 Mustang. We went to New York City, then north through New England and west to Syracuse by way of the Adirondack Mountains before returning to Ohio.

This time we did it right — with new tires, a speedometer that worked and license plates prominently displayed, front and back. And we made several brief stops along the way, just like Tod and Buzz, but without the romances and the fistfights.