|

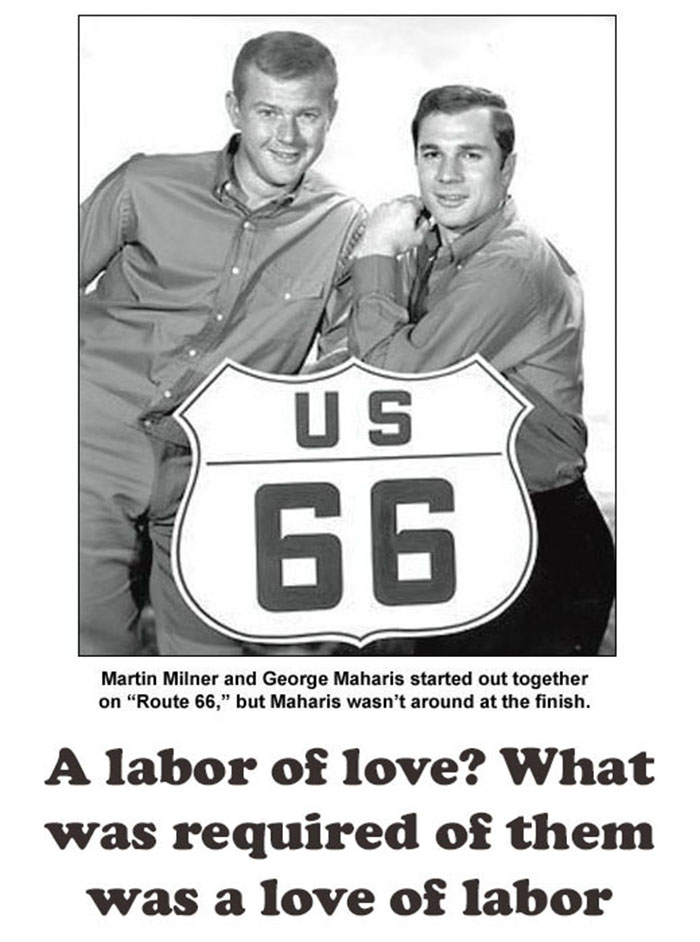

Two of television's most remarkable series were "Naked City" and "Route 66." Both were written mostly by Stirling Silliphant, who must have gone without sleep the whole time the two shows were on the air. Sleep was a luxury for everyone connected with these series, particularly "Route 66" which filmed every episode on location, and seldom stayed in one place for more than three weeks.

What follows are three stories about the program and/or its stars, Martin Milner and George Maharis. Little did I know when I met Maharis in Cleveland in 1962 that the episodes he filmed during this stop would be the last ones he would do for the series. He had talked a lot about leaving the show, but his departure was abrupt and a bit of a surprise. What follows are three stories about the program and/or its stars, Martin Milner and George Maharis. Little did I know when I met Maharis in Cleveland in 1962 that the episodes he filmed during this stop would be the last ones he would do for the series. He had talked a lot about leaving the show, but his departure was abrupt and a bit of a surprise.

Oddly, Silliphant is not mentioned in any of these pieces, although I was well aware of his work and admired his writing, particularly on "Naked City," which was by far the better of the two series, particularly when viewed today.

I'm not sure what the various logistical problems were with "Naked City," which was filmed in New York City. But perhaps no television series ever had a crazier work schedule than "Route 66," which would have looked terrific had it been filmed in color, though that probably was either impossible or impractical at the time.

The first story explains some of the obstacles "Route 66" had to overcome. An interesting docudrama series could have been made from almost every episode, explaining what had to be done in order to film it.

|

| |

Akron Beacon Journal, September 30, 1962

By JACK MAJOR

After the producers of the “Route 66” television show decided last year to film an episode in New Orleans, they sent set builder John T. “Red” McCormack ahead to look over the location.

McCormack searched in vain for a suitable Louisiana shrimp boat, so he ordered his crew to build a reasonable facsimile – in 11 days.

Since the “Route 66” vessel did not have to float, McCormack didn’t lay a keel. He started the hull about halfway up.

Among the interested spectators was an old Cajun who couldn’t believe his eyes.

“Young fella,” he said to the 50-ish McCormack, “you gotta put in a keel.”

McCormack replied that he used a new method of boat-building.

“I said I’d turn the boat over and lay the keel last because it would be easier.”

But the Cajun was not convinced. “You durn fool!” he shouted. “You must be crazy!”

McCormack said his friends often agree with the Cajun's analysis.

When McCormack accepted the assignment to work with “Route 66,” he took on a job that might be impossible for many other men. It’s a tribute to McCormack’s ability – and good-naturedness – that he has maintained his sanity during his 25 months with the show.

“Route 66” is the only series that films entirely on location. As the season approaches the halfway mark in filming, the show runs out of scripts.

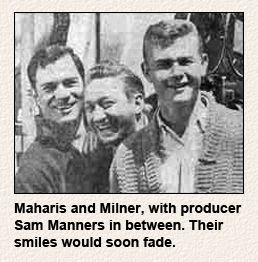

McCormack and the rest of the 60-person television crew are in Cleveland this week filming the second of three shows in northeast Ohio.

“I don’t know what my crew will have to do next week,” he said, “because that script isn’t finished.”

“Route 66” had nine episodes completed for the current season when it rolled into Cleveland. There were only two more scripts finished, and just one of those had been cast.

Co-stars in the first Cleveland episode were Jack Kruschen and Madlyn Rhue, and they weren’t signed for their roles until four days before shooting started.

Kruschen flew into Cleveland on a Wednesday and began filming that evening. He finished at midnight.

“About 1 a.m.,” he said, “I got a call from the director who said weather conditions were going to force a change in the shooting schedule the next day. The new schedule would cover a part of the script I hadn’t even looked at yet.” “About 1 a.m.,” he said, “I got a call from the director who said weather conditions were going to force a change in the shooting schedule the next day. The new schedule would cover a part of the script I hadn’t even looked at yet.”

So Kruschen stayed awake until 3:30 a.m. reading that section of the script and had only a few hours sleep before reading it again later that morning.

Delays in script writing and casting and last-minute changes in the shooting schedule make it difficult for everyone, and much of the pressure falls on McCormack. He must finish his job before anyone else can begin.

McCormack’s work usually includes some hurry-up construction projects and a city-wide scavenger hunt. The first Cleveland episode required both.

McCormack’s initial task was to convert a lounge at the downtown Sahara Motel into a night club. (Executive producer Sam Manners had the more pleasant job of finding 40 beautiful women to fill that nightclub. “We filmed a sort of twist orgy,” said Lou Weiner, the show’s publicist.)

McCormack then went to the Rand Mansion on Lake Shore Boulevard to change a dining room into a gambling den. This was accomplished after he located two one-armed bandits from other homes in the area. Also required were a pool table, a portable bar and some decorative statuettes.

Such items aren’t part of the equipment that travels around the country with the ever-wandering “Route 66” gang.

The show moves in a caravan of five automobiles and five moving vans. These vans carry wardrobe, cameras, lights, dressing rooms and some props, but each location usually has McCormack out hunting for something new or unusual.

Oddly enough, McCormack says his most difficult job is finding good sign painters. Signs are vital for designating the names of cities and towns, but they can’t be prepared until the actual location is chosen. Then it’s a rush operation; McCormack has learned many local painters can’t be hurried.

“In the east last year I had only two days to get signs made for two shows,” he recalled. “I covered 200 miles around Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, stopping at every sign painter I could find, before I got a man.”

One of McCormack’s toughest breaks involved a mine shaft he built in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Before he got the supporting timbers in place, a rare blizzard dumped heavy snow on the area and the shaft collapsed.

McCormack quickly rented a bulldozer, scooped out the rubble and rebuilt the mine shaft.

At Seagoville, Texas, for an episode using flashbacks, the company worked at a dilapidated old house which had to be shown as it looked 20 years earlier. McCormack and a three-man crew brought in shrubs, pre-fabricated wall sections, fencing and latticework and accomplished the rejuvenation in two hours.

Later, in Indio, California, McCormack directed a crew to completely remodel the exterior of a home, building shutters, a fence, a large porch and an additional room. It was all left to the owner in return for his permission to use the property.

The “Route 66” crew travels about 25,000 miles a year because the show’s owner, Herbert B. Leonard, believes real settings are a marked improvement over the make-believe studio backgrounds.

The show thrives on this sort of realism, but McCormack is handy in case minor trickery is needed. Thus, in Lewisville, Texas, McCormack got permission to put up a motel sign on a house on the main highway, Route 77.

The homeowner called McCormack at 2 a.m. asking if he could take down the sign until morning.

“He told me he’d had a steady stream of motorists stopping to ask for sleeping accommodations,” said McCormack, with a smile.

Similar trickery was needed at another location and McCormack convinced a furniture store manager to let him transform a display window space into a cafe setting, with tables, chairs and blue plate special signs.

“The woman who owned the store had been out of town,” said McCormack. “When she got back and saw the outside of her place, she stormed in and started screaming at the manager because she thought he’d turned it into a hamburger joint without telling her.”

The rest of the “Route 66” company sets up immediately after McCormack is finished. Each scene is rehearsed three times before it is filmed. The film is then flown to Hollywood where Leonard supervises the processing and editing.

No one working on location has a chance to see their work until the program is shown on CBS. "We seldom see it even then," said publicist Weiner, "because we work so much at night."

Sometimes it takes more than five hours to get a minute’s worth of film. Actors and members of the production staff spend much of their time waiting to work.

Manners, who supervises all production on “Route 66” and “Naked City,” another Herb Leonard production, is one person who never has to wait. He’s on the go all the time. He selects the locations and sends McCormack to work. When McCormack is finished, it is Manners who schedules the day’s shooting. He also picks the local actors who audition when “Route 66” arrives in town.

(Manners was born in Cleveland and was graduated from West Tech High School. He selected his hometown for shooting “because it has several interesting things to photograph.”)

Manners also has the last word on script changes which are recommended by members of the staff.

“In all,” he said, “I’m going at least 18 hours a day. I’ve gone 96 hours without sleep, and I haven’t had more than an hour’s sleep each night for several weeks.”

He said the work schedule for each member of the “Route 66” crew is at least 12 to 16 hours a day. “We even work Sundays most of the time.”

Even with such an extensive schedule there are times episodes aren’t finished on time.

“We try to do each episode in six and a half or seven days,” said Manners, “but we often work for ten days.”

This puts the show under extreme pressure in January when Manners loses the cushion he had at the beginning of the season and finds himself filming only two weeks before the episodes are scheduled to air.

“We’d like to have eight weeks from camera to can,” said Manners, “but that will be impossible by the start of the new year.”

The lack of time presents a challenge to music director Nelson Riddle, who scores “Route 66” in Hollywood. “He’d like two weeks to compose the music and dub it in,” said Manners, “but sometimes we give him only three days.”

“It’s a miracle this show gets finished,” he said, “but we love it. You know, I’ve still got 96 per cent of the people who started with me two years ago.”

“The casual observer might think this operation is confused,” said Kruschen, during a long break on the second day of work in Cleveland, “but it is the most organized confusion you will ever see.” |

|

| |

Writer Silliphant, who later won an Oscar for his screenplay for "In the Heat of the Night," had a fondness for offbeat titles which became a trademark for episodes of "Naked City" and "Route 66." I don't know if all of the following titles were created by Silliphant, but they were featured on both shows. In any event, they rate among my favorites:

|

Route 66: "The Man on the Monkey Board," "Ten Drops of Water," "Sleep on Four Pillows," "Birdcage on My Foot," "How Much a Pound Is Albatross?," "Blues for the Left Foot," "Hell Is Empty, All the Devils Are Here," "Poor Little Kangaroo Rat," "You Can’t Pick Cotton in Tahiti."

Naked City: "The Man Who Bit a Diamond in Half," "Bullets Cost Too Much," "The Well-Dressed Termite," "Sweet Prince of Delancey Street," "Take Off Your Hat When a Funeral Passes," "The Corpse Ran Down Mulberry Street."

"Ooftus Goofus," "Today the Man Who Kills Ants Is Coming," "The One Marked Hot Gives Cold," "The King of Venus Will Take Care of You," "Five Cranks for Winter ... Ten Cranks for Spring," "King Stanislaus and the Knights of the Round Stable," "Stop the Parade! A Baby Is Crying!," "No Naked Ladies In Front of Giovanni’s House."

|

I never had the opportunity to interview anyone connected with "Naked City," which besides having the wackiest episode titles, offered a wide variety of stories and characters that made it a most unusual police series. Paul Burke's character, Adam Flint, was a college-educated New York City police detective who was one of the most sensitive, intuitive crime solvers television ever had. I never had the opportunity to interview anyone connected with "Naked City," which besides having the wackiest episode titles, offered a wide variety of stories and characters that made it a most unusual police series. Paul Burke's character, Adam Flint, was a college-educated New York City police detective who was one of the most sensitive, intuitive crime solvers television ever had.

Flint would have been a good fit for "Route 66." He was a much more complex character than either Buz Murdock or Tod Stiles. What was interesting is that while "Naked City" could be extremely violent one week, it could be as tame as "The Andy Griffith Show" a week later. Flint was the ultimate Reasonable Man. The fact he had a steady girl friend, an actress played by Nancy Malone, saved "Naked City" from the often ridiculous romances that sprung from nowhere on "Route 66," where our heroes, Murdock and Stiles, were notorious for their instant attachments to the first girl they spotted in every new town.

Murdock and Stiles were like trouble-seeking missiles, and upon impact they'd either explode or offer unsolicited advice, usually a variation on the "money can't buy you happiness" theme. They had at least one fist fight every week.

The program appealed to people who related to the freedom Murdock and Stiles enjoyed while going anywhere they wished, and never staying in one place very long. And traveling in a Corvette was so much more fun than doing it on motorcycles. The car also made the young men less threatening, somehow more respectable.

In recent years I've re-watched several episodes of "Naked City" and "Route 66." There's no comparison anymore. Burke's Det. Adam Flint, his partner, Det. Frank Arcaro (Harry Bellaver), and especially his boss, cynical Lt. Mike Parker (Horace McMahon), are mature men who seldom preach. Yes, the villains, who often aren't villains at all, are troubled in that 1960s way when all problems were conveniently traced back to childhood and bad or indifferent parenting, and they often use strange or vague phrases, many of which wind up as episode titles ("Today the Man Who Kills Ants is Coming"). The series, inspired by a 1948 movie, benefits from the opening and closing narration provided by Lawrence Dobkin, which always ended with "There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them."

On "Route 66," however, Stiles and Murdock came across as wandering psychology students, freely dispensing often contradictory advice based on acquaintances that were made 60 seconds earlier. Heaven help any man who contradicted them. It was a series for its time, but hasn't aged well.

When "Route 66" paid its second visit to Cleveland, in 1962, Murdock (aka George Maharis) was spoiling for another fight, but this time his anger was directed at his bosses.

|

Akron Beacon Journal, October 14, 1962

By JACK MAJOR

Martin Milner and George Maharis portray wandering vagabonds on their television series, “Route 66,” but off-camera only one of them is loyal to his image.

That’s Maharis.

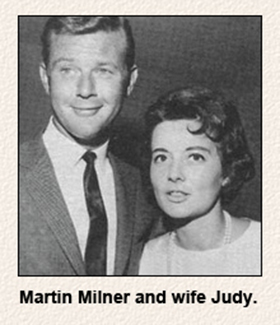

Milner is happily settled in a family rut with a wife (Judy Jones) and three children - Amy, 4; Molly, 20 months; Stuart, four months.

Milner understands his television character – Tod Stiles – but prefers not to live the role. Sometimes his family joins Milner on the road.

Maharis, on the other hand, becomes annoyed when he thinks about losing his freedom, both as a man and as a performer.

Both were in Cleveland with the rest of the 60-person “Route 66” crew to shoot three shows for the 1962-63 season.

This is the program’s third season and it has helped make stars of both actors. However, Milner and Maharis have differing opinions about the futures, particularly where “Route 66” is concerned.

“I’ve already given the producers notice that I’m leaving at the end of the year,” declared Maharis, who said he is still weak from a recent bout with hepatitis. He said his health is the main reason for his decision. “I’ve been working 15 hours a day, and that’s too much. My doctors think I’m nuts.”

But health isn’t the only reason.

Maharis doesn’t hide the fact he's given his personality to Buz Murdock, but now he’s afraid George Maharis may get lost in the process.

“I think I’ve got a lot to say as an actor,” he declared, “but I won’t have if my whole life is tied up with this show. I’ve already told them I want four days off every time we move from one location to another.

“Some people in this business are like mosquitoes. They suck out all your blood and all they leave is an itch.”

Milner doesn’t hold with this view. He’s content to stay with the program for as long as it runs.

“It’s hard work, but it’s interesting,” he said. “Naturally I’d like more time off, but it doesn’t bother me that much.”

Sam Manners, executive producer of the show, said Maharis’ threats to quit are meaningless. “He’ll be back next year because we have him under contract.” Sam Manners, executive producer of the show, said Maharis’ threats to quit are meaningless. “He’ll be back next year because we have him under contract.”

Manners did come up with what might be called The Cleveland Compromise during the area visit. He promised to give Maharis time off later this season while the show is written around him, much the same as it was when Maharis was hospitalized for hepatitis last spring.

When “Route 66” began, Milner was proclaimed the star because of his vast experience in movies and television. Maharis was unknown, getting the television role on the basis of an off-Broadway part in “The Zoo Story.”

Now the situation is almost reversed. Milner is still considered a star, but to Maharis has fallen the title of the show’s “golden boy.”

Lou Weiner, the show’s publicist, goes so far as to say “George could become the next Gable.”

Wherever the program goes to film its episodes, female fans follow bachelor Maharis. They stalk him, chase him, swoon over him and if they can stop him for a minute will offer a full-course meal.

“No fooling,” he said, “wherever we shoot a show they try to feed me. I must look hungry or something.

“In Arizona I was offered a buffet lunch. Some ‘buffet.’ I was supposed to go through three baked chickens, a pound of mashed turnips, a couple of pounds of potato salad and more fudge than I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Some of Maharis’ older lady fans caught up to him in Cleveland last year and promised to send him goodies.

“They said I probably wasn’t eating right, being on the road so much. I still get about ten pounds of cookies from them every week.”

Milner travels as much as possible with his family. His wife and children made the trip to Cleveland and the five of them stayed at a home in Lakewood.

“I’m not bothered by fans the way George is,” said Milner, crediting his relative privacy to the presence of his wife on the set.

Milner devotes his working time solely to “Route 66.” “I used to have some outside businesses, but not anymore.”

Maharis has an outside activity – his singing career – which has taken away most of his spare time. His first record, “Teach Me Tonight,” was a hit and his two albums also were top sellers.

“I’m not like a lot of those TV actors who become singers,” said Maharis. “I can sing and I’m good at it. And I have done it without capitalizing on the television show."

This is one area where Maharis separates himself from the character he plays.

“I had my choice of six record companies, but I went with the one that promised it wouldn’t publicize my connection with ‘Route 66.’ In fact, the producers of the show wanted to have me sing, but I told them George Maharis sings ... Buz Murdock doesn’t.”

Both Milner and Maharis are sponsor conscious. Well, why not? Each drives a Corvette similar to the one seen on their program.

“We got them free, but that’s not why we drive them,” said Milner, who also owns another Chevrolet.

When Maharis arrived at the Cleveland airport – most of the crew traveled by auto or truck – he refused to ride in a car that wasn’t manufactured by his sponsor.

Milner drove to Cleveland with his family, including their pet dog, Cupcake, a shaggy terrier. Milner drove to Cleveland with his family, including their pet dog, Cupcake, a shaggy terrier.

“There’s an interesting story about the dog,” said Milner. “They wouldn’t let me bring him along with the show until he went to a behavior school. So I enrolled him in a six-week course in California and went to Pittsburgh where we filmed some shows. A few weeks later we got to Boston, where I expected the dog to join me. I called the school to find out when Cupcake would arrive, but they told me he flunked the course. He passed it the second time around.”

Milner speaks quietly and deliberately about himself and his career. He warms as the conversation progresses.

Maharis comes on like gangbusters and never stops. He asks as many questions as he answers.

Both are in their early 30s, but Milner – in person – looks like he just got out of college. Maharis looks older off screen than on. He has a toupee that gives him that fluffy dark wave and covers a hairline that has receded about three inches.

The show calls for several action scenes and the actors do most of them without stand-ins.

Milner and guest star Lee Marvin were involved in a fight scene last year in Pittsburgh when a rare mishap occurred. Milner threw a punch and Marvin forgot to duck. Marvin required 27 stitches to close a wound on his face.

The stars are as versatile as they appear on screen.

“They’ve never asked me to do anything I haven’t done before,” said Milner.

Writers have made Milner play tennis, shoot pool, ride horseback, water ski, pilot a plane and race an automobile and a hydroplane.

“Some of these things have made the show fun,” said Milner. “I especially enjoyed the show where I handled the hydroplane. Besides, it was a good program, with comedy, drama and action.”

Milner has been acting since he was ten. Maharis is a latecomer and has acted seriously about six years.

People often refer to Milner as “an old pro” and sometimes speak disparagingly of Maharis as a method actor.

Maharis admits being influenced by drama coach Lee Strasberg, but denies belonging to any acting “school.”

“I read the script and then put it down and try to think why my character acts the way he does. I feel my part.

“When I play a scene, I listen to the other actors and answer the way I would if the scene were part of real life.

“Sure, sometimes I don’t speak my lines exactly the way they’re written.

“Maybe I’ll give the cue to the other actors in the middle of a sentence, but it really gripes me if they start to answer before I finish. This means they’re not listening to me ... that they’re only concerned with their lines and not the whole show.”

These days, however, Maharis is more concerned with the show’s producers ... and whether they are listening to him. |

|

| |

Apparently I had caught Martin Milner at a bad time. George Maharis has given interviews over the past thirty years or so in which he denies he had any problem with Milner, or vice versa. But in some interviews he gave in the early 1960s he was  critical of his co-star, complaining Milner didn't take the time to visit him when he was hospitalized for hepatitis and calling Milner a snob. critical of his co-star, complaining Milner didn't take the time to visit him when he was hospitalized for hepatitis and calling Milner a snob.

Milner may have been a bit jealous of Maharis' popularity, and he certainly could have been upset that his co-star was about to walk off the show. If Milner, the family man, was putting in 16-hour days when he was sharing the load, he probably felt the work would be even more grueling when the full weight of the program was put on his shoulders.

Later Milner would have another hit series in "Adam-12," and as years went by I'm sure he and Maharis patched things up, at least in their minds. I don't think they've ever had much occasion to see each other. From what I've seen and heard about Milner, he's a class act and thoroughly professional, having started in the business when he was a teenager.

Milner died in 2015. He was 83, and had a long career that featured roles in several fine movies before "Route 66" came along. Among the films: "Sands of Iwo Jima", "Halls of Montezuma", "Mister Roberts", and "Sweet Smell of Success".

No doubt Maharis has always been more personable and opportunistic. While Milner didn't seem to enjoy interviews, Maharis thrived on them. He and I talked again about nine months after he left "Route 66." It won't show up in the following story, but Maharis had an amazing ability to recall incidents and comments from previous interviews. He also had a knack for appearing to be candid and completely honest. Perhaps everything he said was true ... or perhaps he simply believed that it was.

|

| |

Akron Beacon Journal, July 14, 1963

By JACK MAJOR

The fight is still going on between George Maharis and his former bosses on the “Route 66” television show, but the tide of battle has taken a turn in Maharis’ favor.

Now it looks as though Maharis may win the war.

He won an important round in the fight two weeks ago when he appeared on “Talent Scouts,” the CBS-TV summer replacement for “Red Skelton.”

Until then Maharis had been kept bottled up by the “Route 66” legal department. From the time Maharis left the TV series last fall until his appearance on “Talent Scouts” July 2, he had accepted only one other television offer.

That offer was from “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and Maharis’ appearance that time was effectively blocked by an injunction from “Route 66” lawyers. Thus “Talent Scouts” was Maharis’ first television exposure in months.

“Route 66” officials maintain Maharis is under exclusive contract and cannot work elsewhere without permission from the show’s owners, Lancer Productions and Screen Gems.

“Nonsense,” countered Maharis. “When CBS bought ‘Route 66’ for the 1963-64 season, the network made the deal with Marty Milner and Glenn Corbett as co-stars. As far as I can see, this deal set me free to work whenever I please.”

The war between one of TV’s most successful shows and one of TV’s most popular leading men has continued for more than a year.

It began in the spring of ’62 when Maharis returned to the show after spending a few weeks in a hospital where he was treated for hepatitis.

“After I was released from the hospital I was supposed to work only six to eight hours a day,” he claimed, “but ‘Route 66’ kept me going 14 to 16 hours a day, SEVEN DAYS A WEEK.

“I collapsed in St. Louis last fall during the ninety-sixth work hour of the week.

“That’s why I’ll never go back to the show. Those people just have no consideration for my health. They’ve got to learn that show business has changed. There isn’t any more Old Hollywood where a company can buy movie stars like pieces of meat.”

People at “Route 66” say Maharis is biting the hand that made him a star. He was an unknown actor from off-Broadway before “Route 66” went on the air. Soon he became one of the hottest names in television because he was credited for drawing most of his show’s audience.

Maharis thinks there is no merit to the complaints against him. “The show’s producers have never admitted it,” he said, “but I was ordered to leave the show by doctor’s orders. And it wasn’t my doctor, it was theirs. I’m still too weak to work full time.”

Therein lies the problem: How sick is Maharis? He says he is still ailing; the show’s producers say he is using his “illness” to get out of the series.

I met Maharis last fall when “Route 66” came to Cleveland to film three shows. Those were the last programs he did for the series.

Maharis and the producers had discussed a temporary truce in Cleveland. The actor promised to continue working if the producers gave him time off before moving on to St. Louis.

When I met Maharis he was grumbling, and he predicted he would leave the show for good at the end of the season.

The producers assured everyone Maharis was bluffing. They said the star was bound by contract to remain with the program even if it continued on television until 1980.

Two weeks later Maharis left – and has not returned.

For the next several weeks he rested in a hospital, then went into semi-seclusion at his New York City apartment. His only work during that period was done in a recording studio where he continued his flourishing singing career.

Then CBS and "Route 66" reached agreement for another season ... and Maharis used it as a cue to go to work on his own. He was booked to sing on the Sullivan show in May, but the “Route 66” injunction stopped him.

A few weeks later I met Maharis the second time, while he was in Cleveland promoting his latest record.

Maharis is easy to like and perhaps too easy to believe. He’s cocky, but congenial, and so very, very convincing. He seems to have a healthy ego, but he listens as well as he talks, and he’ll talk at length at the sound of “hello.”

He says he expects to win his legal battle over the Ed Sullivan appearance. “Sullivan has already rescheduled my song for early this fall,” he said.

Maharis also completed a role in a Davis Susskind television production. The play, “An American Dream,” is part of a series that Susskind hopes to syndicate this fall.

Recently the “Route 66” producers made what they considered a peace offering. They asked Maharis to return to the show.

“They want me because they need me to get ratings,” said Maharis. “But get this - ‘Route 66’ refuses to rerun my old programs. This is like cutting off your nose to spite your face.

“The whole campaign against me is just a personal vendetta. ‘Route 66’ has no legal hold on me. The show is just trying to scare everyone away from me.”

Maharis’ importance to the show is undeniable. Despite sharing the spotlight with co-star Martin Milner, a more experienced actor, Maharis is, according to ratings, the key ingredient in the show’s success.

“I think CBS renewed the series for next year as a favor to Screen Gems,” said Maharis, who expressed sympathy for Corbett, the young actor hand-picked to succeed him.

“Corbett looks a lot like me, but he acts more like Milner. Poor guy. I understand the directors always tell him, ‘Do it this way because that’s how George does it,” or ‘Do it that way because George does it that way.’ ”

Maharis’ long absence from television apparently hasn’t hurt his popularity. He said he has several offers and is simply waiting for an OK from his doctor before accepting some of them.

“I’m not in a hurry, though, because I make a good living from my records.”

Included in the offers, he said, are ideas for television series, movies and Broadway shows.

“What kills me,” he said in half-amusement and half-disgust, “is that one of the television series offers came from Screen Gems.” |

|

| |

Maharis' career soon resumed, though it was all downhill after "Route 66." He starred in a few increasingly awful movies – "Quick Before It Melts" (1964), "The Satan Bug" (1965), "The Happening" (1967) and "Land Raiders" (1969) – and had one more television series, "The Most Deadly Game," which was axed 13 episodes into the 1970-71 season. He appeared as a guest star in several prime time shows, including two episodes of "Murder, She Wrote" in 1990.

While his personality was a good fit for moody, hot-headed Buz Murdock, Maharis never became a particularly good actor. At least, not in my opinion. Perhaps his personality was too strong. Still, some thought he had star quality. Obviously, he didn't. Today the comment by the "Route 66" publicist that Maharis could become "the next Gable" seems ridiculous.

Of course, Maharis was never really the ladies' man he appeared to be on "Route 66." He posed nude for Playgirl magazine, but it was more for the benefit of his male fans. Eventually he was open about his homosexuality, but it first became apparent through two arrests, the first for soliciting a male undercover officer, the second for having sex with a male hairdresser in a restroom. Being gay is one thing, soliciting sex in a public bathroom is quite something else. To Maharis' credit, he remained true to himself and as outspoken as ever.

At age 88 (as of 2016), Maharis is retired. The last time I checked — in 2011 — he was still an engaging fellow who loved to talk, especially about himself. At that point he was still giving interviews about "Route 66." For yet another look at the actor, check out this story.

|

| |

| Martin Milner on the Internet Movie Database (IMDb.com) |

| George Maharis on the Internet Movie Database (IMDb.com) |

| |

|