When it comes to exploring,

I'm more inept than intrepid

By JACK MAJOR

Don't go chasing waterfalls. That was the sage advice offered in a TLC song that came along too late to prevent me from making ridiculous, potentially dangerous mistakes during quests that proved I am one of the world's worst explorers.

The preface to my tale is a daytrip in the late 1940s. A cousin, Joe Smolinski from Highland Falls, NY, was visiting Solvay. Joe would be ordained a priest a year or so later. He had brought along another seminary student. They wanted to visit Niagara Falls, about 150 miles away, and they invited us to join them. ("Us" was four Solvay cousins old enough to make such a trip – Bimby, Bobby and Tommy Smolinski ... and me.)

The trip was delayed by (of all things) a chess game. Bimby had taken up the game and the rest of us were learning to play. Joe (soon to become Father Joe) played chess and I challenged him to a game. I played what you might call "kamikaze chess"; that is, I'd engage in a series of suicide moves, hoping that after the board cleared a bit, I'd still have my queen and one of my rooks and my opponent – who'd gotten careless in the frenzy of my reckless attacks – would be left vulnerable. One thing was for sure, when you played chess with me, the game didn't take long. Except for the one I played that day with Father Joe. It dragged on and on. I guess I was trying to impress him . . . or he was stringing me along.

WHEN WE finally departed for Niagara Falls, it was about an hour later than we'd planned. This was before the New York State Thruway, so we traveled US Route 20 and/or New York Route 5 (which were the same over long stretches) and the trip took almost four hours, which resulted in us getting a rather brief glimpse of Horseshoe Falls and American Falls.

Actually, I'm assuming I looked at the falls . . . because I don't remember seeing them. Not on that trip, anyway. I did go back several years later with my first two children, during my period as a single dad. We took a good, long look that day, from several angles (and I took a few photos, including the one above, from the Skylon Tower).

What I do remember about the trip with Father Joe was the Italian restaurant where we ate dinner before heading back to Solvay. It was one of those red sauce places that for many years gave folks a false impression of Italian cooking. What I recall most is the menu and the item I ordered: spaghetti with meatball. That's right, meatball. I'd never used the singular before. My mother always served maybe three meatballs on a dish of spaghetti.

BY THE TIME we got back in the car, the sun had gone down, and in the darkness our return trip became an adventure. Among my memories: a sign that pointed the way to Youngstown. I knew just enough about geography to figure Joe somehow had wound up in Ohio.

Luckily, it turned out this particular Youngstown is a village north of Niagara Falls, which still meant we were going in the wrong direction, but at least we hadn't left New York. (A few minutes later I would learn that the Niagara Falls-Buffalo area also has a town called Akron.)

We got back to Solvay shortly after midnight and chalked up the trip as a fun way to have spent the day, except for getting shortchanged on the meatballs.

IT WAS AROUND this time that my mother's best friend, Stella Pawlik, and her husband, Al, purchased a farm house in a rural area about 20 miles west of Solvay, near Skaneateles. At least, that's how I remembered my father locating it, but, again, I was a young passenger, not the navigator, when we visited the Pawliks.

It was in a pile of firewood that Al had stacked outside the house where I saw my first snakeskins. For me, it was a scary sight, in sharp contract to what my son Jeff would experience almost 30 years later in the woods behind an apartment complex in West Warwick, RI. (See Sleeping with a Snake.)

Snakes aside, the Pawlik farm was one of my favorite places because of a stream that bounced down a large hill across the street. From the house you could see a waterfall where I'd go to escape the adults while they talked about whatever adults talked about in the late 1940s and early '50s. With my father it was often politics, especially when he and Al Pawlik got together because they both liked to argue, my father on the left, Al so far to the right that he'd make Rush Limbaugh look like a flaming liberal.

Often one of my cousins went with us, either Tom or Jim Smolinski, and we took to exploring the waterfall that was visible from the Pawlik place. (In the photo at the top, that's me in front of Jimmy Smolinski, my sister Mary Beth, and my mother.)

One day, either Jim or Tom and I set out to discover how many waterfalls were on that hill. As I recall, we climbed five of them before we figured we'd been gone long enough, my parents might be getting concerned. We promised ourselves that during our next visit we'd explore the area further. Trouble is, there would be no next time because Al and Stella sold the place a few months later.

As an adult I would try to find those waterfalls. More on that later.

DURING THE SUMMER between graduation from high school and my freshman year at Kent State University, I heard about a place that was described as "the Grand Canyon of the East." That place is Letchworth State Park, located about 60 miles south of Rochester near a town called Mount Morris. The Genesee River runs through the park and in the process drops over three scenic waterfalls

I was curious. So I found a date willing to accompany me to Letchworth. Nancee Higbee, wherever you are, I apologize. Again.

What happened that day was one of the dumbest things I've ever done. It was so monumentally stupid that I briefly insisted that, no, this was not a mistake; this is what I intended to do . . . we climbed the mountain because it was there. And we didn't even need Sherpas.

You see, I had been promised three waterfalls, each one noticeably higher than the one before. I counted only two, figuring there was a trick to reaching the overlook for what was supposed to be the biggest, most spectacular sight Letchworth had to offer.

I thought I had found the way to the overlook, and that way was up a hill. Nancee had her doubts — after all, there was no beaten path to follow — but she was a good date and willingly accompanied me up a hill that became steeper and steeper, the brush so thick that I wished I had brought along a machete.

FINALLY, we made it to the crest — and found ourselves standing on railroad tracks about 50 yards from a trestle that supported a bridge that crossed the canyon. Had there been a train roaring down the tracks, we probably would have been killed. Heaven knows what the state police would have made of it.

I think that was my last date with Nancee.

Several years later I returned to Letchworth twice during family visits to Donnan Farm in nearby York, NY. Both times I had no trouble locating all three waterfalls. And both times I spotted the railroad bridge in the distance, way up high, and wondered if I was the only idiot who ever mistook it for an observation deck.

AFTER MOVING to Rhode Island in 1969 I went through a period in which I dragged my then-wife Karla and our children, Jeff and Laura, on daytrips to places I had seen pictured in brochures and various publications that promoted the state's attractions. As a newcomer, I was fascinated by the size of my new home state. It was just a bit larger than Onondaga County where I had grown up. And it was all laid out in a state map that I foolishly believed was like other state maps — that is, I trusted that roads shown on the map were real, that they were paved and easy to follow.

Wrong. As I would discover when I set out one Sunday to find a place called Stepstone Falls. (Sometimes spelled Step Stone Falls.)

Let me explain that I was using a large, fold-out map published by the state. If you look at a map of Rhode Island in your typical road atlas publication, you won't see Stepstone Falls. Had I checked such an atlas, I might have had a clue that finding the place would not be as easy as the state's map made it seem. All I knew is that the state of Rhode Island considered Stepstone Falls a sight worth seeing — even though the highest "falls" at this place is about 24 inches.

The state map indicated there were two ways of reaching the falls. Since I was vaguely familiar with state route 102, I began my search there, turning west on a road that intersected the highway. For a few miles, the trip proceeded as I had imagined, but then, after turning left to head southwest on the road that would deliver me to the falls, things went awry. The road got narrower and narrower, the pavement gradually disappearing in the underbrush. Finally, the road seemed to end; to continue I'd have to drive through a narrow space between two bushes and hope for the best.

I should have done one of those back-and-forth, get-out-of-a-tight-space turnarounds that takes about fifteen minutes to complete, but it was at that moment that I was once more afflicted by . . . I think the medical term is Galloping Stupidity.

NEVER MIND that my wife wants me to abort the mission. Never mind that our two kids are in the backseat screaming. Never mind that I see no road in front of me. I lurch the car straight ahead, through the bushes, and, miracle of miracles, the road does continue . . . in a backwoods, cue the "Deliverance" soundtrack sort of way.

Just ahead, around the bend, I find it. Stepstone Falls. There are even two cars parked at the side of the road, though later I conclude they were abandoned weeks, months, maybe even years earlier.

I park, we explore. Briefly. Did I mention it was April? And we're deep in the woods? It was a pleasant, spring day when we left our home in North Kingstown, but here at Stepstone Falls we've gone back in time to February. And finally I concur with the suggestion made by my wife and seconded by our kids: Let's get the hell out of here!

Karla was momentarily relieved . . . but she had failed to notice that my Galloping Stupidity had advanced to a dangerous stage. I'd get us out of there, all right, but I was determined to find a better way.

Except there was only one alternate route, and that was uphill on what should have been called The Devil's Stairway because the road went steeply up about 20 feet, then leveled off briefly, then went up another 20 feet, then leveled off briefly, then up again . . . and so forth. How many steps it would take to reach the top of the hill I don't know, because each step was buried in snow that hadn't melted from a storm several weeks earlier, and probably wouldn't melt until July.

Yet I gunned the Ford station wagon and roared up the hill, only to get stuck in snow on the first step. Meekly (and about as carefully as I've ever driven in my life) I backed down the hill, turned around, and retraced my steps. This time those bushes that blocked the road were a welcome sight. Once past the bushes, it was clear, but slow sailing for about five miles.

INCREDIBLY, I drove back to Stepstone Falls several years later, this time with my second wife, Linda, and our daughter Meridith. I took a different route, one that put us at the top of the hill where I discovered you could park your car and walk down to the falls. This was the way God intended people to reach the falls. Along the road on the way to the parking lot were the sites of a small music festival and a stable where two of Meridith's friends had taken riding lessons. If only I had known a few years earlier . . .

And so for a couple of years Stepstone became an occasional destination for hiking and relaxing, though, as indicated the falls themselves are rather ordinary. Which I should have kept in mind the day I decided the time was right — it was August, after all — to skip the parking lot and drive down that hill to park by the water. After all, the state must have improved the road by now.

That kind of reasoning was a clear indication I was having a relapse.

HAVE YOU ever seen "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World?" Do you remember the scene where Phil Silvers picks up a kid who needs a ride to his home in the middle of desolate mountain region and promises to show Silvers a dirt-road shortcut that will help him get back on a highway and possibly beat the other people who are racing to find the buried fortune? And do you remember how impossibly steep and tortuous that "shortcut" was?

Well, that's how the Stepstone road looked when I began my descent. And when you begin your descent, you've reached the point of no return. They could build an amusement park at the top of that road and the most thrilling ride would be the one we took down to the falls. We'd level out briefly, then — whoops! — tip forward again. I believe that road drops at the sharpest angle allowed by the law of physics.

Luckily, the car was still in one piece when we reached the bottom. I parked and we toured the area on foot, taking longer to appreciate nature's beauty than we had ever done before. Not that we were really appreciating nature's beauty. We were simply postponing the inevitable — finding our way out of Stepstone . . . because we knew for sure there was no way I could drive back up the hill.

The good news: the low road out of there had been improved. I escaped without pruning any bushes.

The bad news: the road looked different somehow. It just went on and on and on. I saw no intersection where I could turn right and connect with Route 102.

Finally, an approaching car. I rolled down my window and signaled for the driver to stop. He smirked at my question (apparently one he had been asked several times) and gave me directions that led me back to familiar territory. As soon as we knew for sure we were headed home, Linda made me take the pledge to never ever return to Stepstone.

LINDA DIDN'T know it, but even though I kept my Stepstone promise, she wasn't out of the woods. Several years later, when Meridith was grown and able to trust her parents to take trips without her, Linda and I went to Syracuse for a high school reunion, a three-day affair. With nothing scheduled one afternoon, I talked her into a drive to Skaneateles where we sometimes had lunch or dinner at the Sherwood Inn. Maybe I promised we'd stop there, I can't remember, because the real purpose of the trip — and I was up front about it — was search for the farmhouse that once upon a time had been owned by Al and Stella Pawlik. More specifically, to find the waterfall across the street from that farmhouse.

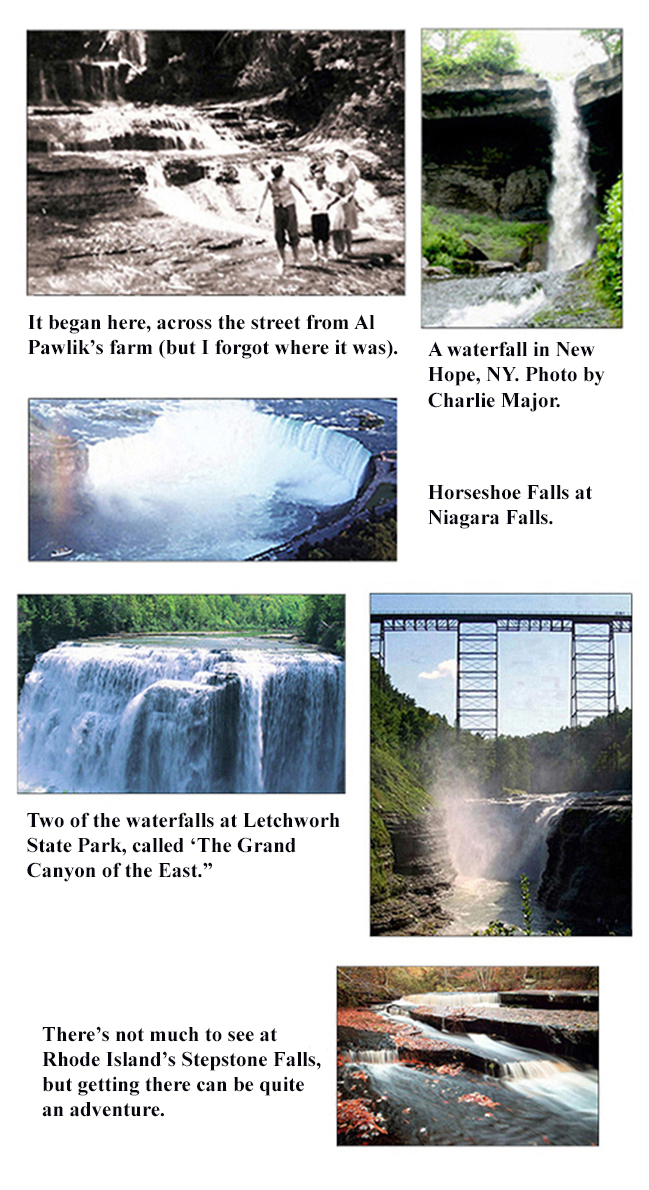

Thus began the Grand Tour — Skaneateles Falls, Mottville, Mandana and New Hope. One by one I struck out, though I really had my hopes up about New Hope. There seemed to be a stream coming down a hill that might result in a series of waterfalls . . .

But it was not to be, at least not for the waterfalls I was searching. I did get out of the car in New Hope on state route 41A, near a mill that is a well-known local landmark. I walked to a barrier along a small bridge over the stream that flows into nearby Skaneateles Lake. And when I reached the barrier I looked down and was stunned at the sight. No, it wasn't what I was looking for, but it was spectacular nonetheless . . . because the stream drops much further from the mill than I thought possible. That is one deep gorge, and finding it made the trip worthwhile. For me, anyway. Linda's mood wasn't lifted until we doubled back to Skaneateles and reached the Sherwood Inn about 20 minutes later.

I NEVER DID find what we used to call Al Pawlik's Falls. I still think it's somewhere between Skaneateles and Owasco lakes, but, then, I don't recall actually seeing either lake when my father drove to Pawlik's farm.

However, an article found on fultonhistory.com, from an Auburn, NY, newspaper, mentioned the A.W. Pawlik place near Moravia, which — drum roll — is between Skaneateles and Owasco lakes. This is not far from New Hope, incidentally.

If I ever get back to Central New York, I'll give it one more try, though I'll probably have to do it all by myself.