|

Singer Nat King Cole, one of the country's most popular singers for many years, accomplished much in his career. For one thing, he was the first African-American performer to be host of his own network television show, in 1956. It had good ratings on channels that carried it, though some outlets,, mostly in Southern cities, refused to present the show, and some sponsors dropped out as a result.

When I interviewed him over the telephone in January, 1964, Cole was hopeful he'd have a second crack at television. Certainly he had become a more visible performer, with guest spots on other television shows and appearances in movies. He also was one of the best-selling recording artists in the world.

He had several songs, including one of the most enduring, "The Christmas Song," written by Mel Torme and Robert Wells. Cole also had one of the strangest hits of all-time, "Nature Boy," though, to be fair, there were a lot of weird hits in the 1940s and '50s, including "The Cry of the Wild Goose," "The Little White Cloud That Cried," and "The Thing."

However, while several other singers eventually did a version of "Nature Boy," I don't think the song would have become popular at all if it weren't for Cole's rendition. The man had a silky, magical voice. Incredibly, he might have kept that voice a secret if it weren't for a nightclub owner who ordered him to honor a patron's request one evening. |

Akron Beacon Journal, January 19, 1964

The 1963-64 television season may be recalled as the one in which black performers received some long overdue opportunities.

The change this season has been noticeable both in programs and commercials. While the change is welcomed in both areas, it is commercials, strangely enough, which represent the more significant breakthrough.

Here, for instance, we now have Wally Cox pitching his fortified detergent to a Negro mother and her son. A few months ago, advertisers were simply too scared to do such a thing.

Consider the case of Nat King Cole, one of the giant in the entertainment business.

He had a television variety program in 1957, but it as short-lived.

People liked it. Critics liked it. Performers liked it, like it so much they often worked on it for minimum payment in an effort to save the show.

The network — NBC — liked it and so did potential sponsors. But those would-be sponsors weren’t willing to risk an investment. They frankly admitted they were afraid business would suffer if they sponsored an African-American.

NBC continued the show several weeks, hoping sponsors would change their minds. Eventually the network dropped the program, citing financial reasons.

Now it looks as though the situation is changing.

Cole, in a telephone interview last week, said ABC is considering reviving his program as a summer replacement for one of the network’s many expendable series. ABC apparently i sure it could find sponsors.

Cole and the network already have worked out two deals. The first resulted in a Sunday night presentation last fall of a program the singer taped in England. The second deal will materialize in March when Cole will be host of ABC's Saturday night shindig, “The Hollywood Palace.”

Not that Cole needs a TV series. His business is music, and in that business he has few peers.

But it’s only human nature to be annoyed when the color of your skin is the only reason you are deprived of something you deserve. Thus it’s a challenge for Cole to break the racial barrier and get his own show, sponsors and all.

At the same time, Cole does not regard himself as a crusader for his race.

“I speak only for myself on the racial situation,” he said. “I can’t speak for other Negroes because I’m sure their experiences have been different from mine.”

If the TV series does develop, it will cape one of Cole’s most successful streaks.

It began last year when he chalked up two hit records — “Ramblin’ Rose” and “Those Lazy, Hazy, Crazy Days of Summer” — and found himself for the first time since the 1950s with a substantial following among teenaged record buyers.

Meanwhile, he reinforced his standing as one of the country’s most popular nightclub and concert performers, while maintaining his reputation as one of the few singers important enough to make a living from album sales.

The busier-then-ever Cole is also doing a lot of TV guest shots this season. He has one scheduled for Tuesday night on “The Jack Benny Show” on CBS.

One might conclude then that 1964 would be a great year for a guy like Cole to be starting out on a career. Just look at the opportunities.

Not so, Cole countered. Just look at the competition.

“I’d hate to start out in today’s recording business,” he said. “It’s a real rat race. Everybody’s getting into the act. Gimmicks are replacing musical integrity. Maybe a person comes along who can play 19 drums at one time. This is in demand for a few weeks; then the guy is washed up.

“I find it disheartening to see the lack of stability in the recording business. The companies are building stars like they used to. If a singer has a flop recording or two, the company simply replaces him.

“I was lucky to come along at a time recording companies had the patience to develop talent.”

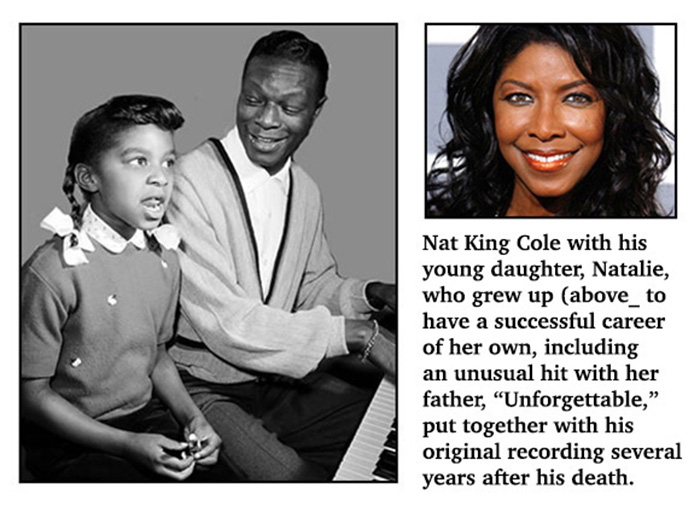

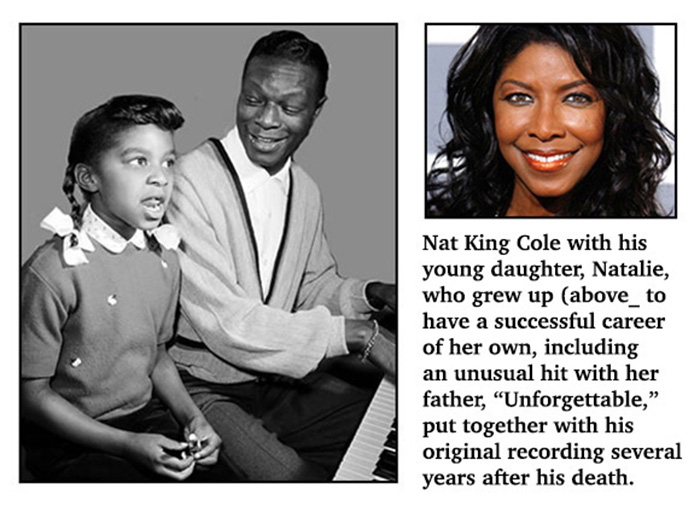

Cole was especially lucky because he was signed by Capitol Records in 194 as a pianist. No one — not ever Cole — suspected he would become a singing star. He made his singing debut — involuntarily — when a nightclub owner ordered Cole to comply with a request from the audience for vocal numbers.

At the time, Cole headed a trio featuring bassist Wesley Prince and guitarist Oscar Moore. Originally the King Cole Swingsters, they became better known as the King Cole Trio.

As a singer, Cole didn’t create an immediate sensation. He said one member of his first audience, a doctor, told him, “Son, with a throat like that, you should be home in bed.”

However, that is ancient history. The irony is that today hardly anyone remembers that Cole is an outstanding jazz pianist. |

|

Tragically, Cole died just 13 months after our interview. A heavy smoker most of his life, Cole died of lung cancer. Months before his death, Cole and Stubby Kaye filmed their roles in what would be one of the movie hits of 1965, "Cat Ballou," playing the Sunrise Kid (Cole) and Sam the Shade (Kaye) who bridged several scenes with short musical interludes that advanced the plot.

Jane Fonda and Lee Marvin starred in the unusual Western, with Marvin playing two roles, as brothers, and receiving a best actor Oscar for his memorable performances. |

|

| |

|