|

A common theme in my interviews with actors who had enjoyed movie careers in the 1930s and '40s was their disdain for television. They had been forced to accept the new reality — that most of their future work would be on the small screen — but they didn't like it.

I was familiar with Carson's work, but would not have a full appreciation of the man's versatility until it was too late to talk to him. (He died less than five months after our interview.) I think he would have had a lot of interesting things to say about the way Hollywood operated during the heyday of the studio system, and how actors and actresses with a flair for comedy were underrated.

A perfect example of Carson's acting ability can be seen in "Roughly Speaking," a poorly-titled 1945 film that cast him as the second husband of Rosalind Russell, who played a woman determined to succeed in a man's world. Carson makes an unforgettable entrance in that film, and holds court until his character's death several years later.

When I met Carson it was in connection with a play he was performing at a summer theater in Canal Fulton, Ohio, a few miles south of Akron. He was only 51 at the time; I expected he'd be around for many years to come. He was on his fourth marriage, to Sandra Jolley, and we never got around to mentioning his third wife, Lola Albright, who was an Akron native.

What was most on his mind at the time was television, and the reasons he didn't like the medium: |

Akron Beacon Journal, August 19, 1962

You’d almost think it was a conspiracy . . . the way actors talk about television.

None of them seems to like the medium. “It’s all right to visit — as a guest,” said one actor, “but I’d hate to live there — on a series.”

So it was no surprise when Jack Carson, who was amazingly busy in movies for more than 20 years — in his first year in Hollywood, 1937, he appeared in no less than 14 films — joined the anti-TV chorus. He sounded off during his visit to Canal Fulton, where he performed in “Make a Million,” a three-act comedy that enjoyed a 308-show run on Broadway four years ago.

“It’s a compromised medium,” Carson said of television. “The writers aren’t allowed to write the way they want to; the actors are rushed so much they can’t give decent performances, and the directors have such a schedule they can’t direct at all; they’ve got to be satisfied with simply finishing a show.”

About the only people who don’t have to compromise, Carson complained, are network bosses and sponsors. “They just get richer. Do you know why there’s a trend toward hour-long shows? Because networks found they can sell more commercials and make more money, that’s why.”

CARSON BELIEVES people would prefer to see more half-hour shows.

“Besides,” he declared, “there are some things that should be done in 30 minutes. I’m a big Red Skelton fan, but I don’t think Red can do his kind of show for a whole hour every week.”

Skelton’s show jumpst to 60 minutes this fall.

Carson has a more personal reason for arguing against hour-long shows.

“I just finished filming a 30-minute show,” he explained, “but the producer called me a few days ago and asked if I wouldn’t mind expanding the story to an hour. We couldn’t sell it as a 30-minute piece.”

THAT DIDN'T surprise the actor. This season, for example, an independently produced 30-minute offering could have been sold to only four shows — “GE Theater,” “Alfred Hitchcock,” “Twilight Zone” and “Alcoa Premiere.” All other half-hour showshad regular series characters that had to be included in the cast every week.

The 1962-63 season is even more exclusive. “GE Theater” has been scratched, while the other three are being expanded to an hour.

So Carson has to pad his effort.

“The story can be told in 30 minutes, so we’ll have to beef-up our main character,” he said. “Television does this all the time . . . stretches a weak story.”

WHEN CARSON completes the extra 30 minutes, he can negotiate with those three shows. “Hitchcock” and “Twilight Zone” are likely to rule it out for lack of a surprise mystery element, so lotsa luck.

Carson has no other TV plans this fall. He figures he’ll probably be offered guest shots, but there’s nothing set yet. He’ll return to California in September and is interested in at least two movie scripts.

Like other TV haters, Carsons does see a glint of light on the tube. That’s from 8:30 to 9:30 on Saturday nights.

“ ‘The Defenders’ is a great show,” he said, crediting the quality to the freedom the show allows its writers. “And don’t forget E. G. Marshall . . . a great actor.”

WHILE CARSON has never watched “Ben Casey,” he has been interested in the show’s success.”

“I helped discover Vince Edwards,” Carson recalled. “It was back in 1951, and we found him in New Yorkk when we were looking for someone to play a wrestler in the move, ‘Mr. Universe.’ ”

The surly “Ben Casey” star had his hair bleached for that movie in which he spoofed Gorgeous George.

CARSON'S STATEMENTS continued to fit a typical pattern, so it was no surprise when he said he’d like to have a successful Broadway show some day.

“People tell me I’m one of the few actors who can carry an audience from laughs immediately into a serious mood,” he stated in self-evaluation.

Therefore, a Carson play would have to have dramatic moments as well as the light. This is part of a fight Carson has been waging for years.

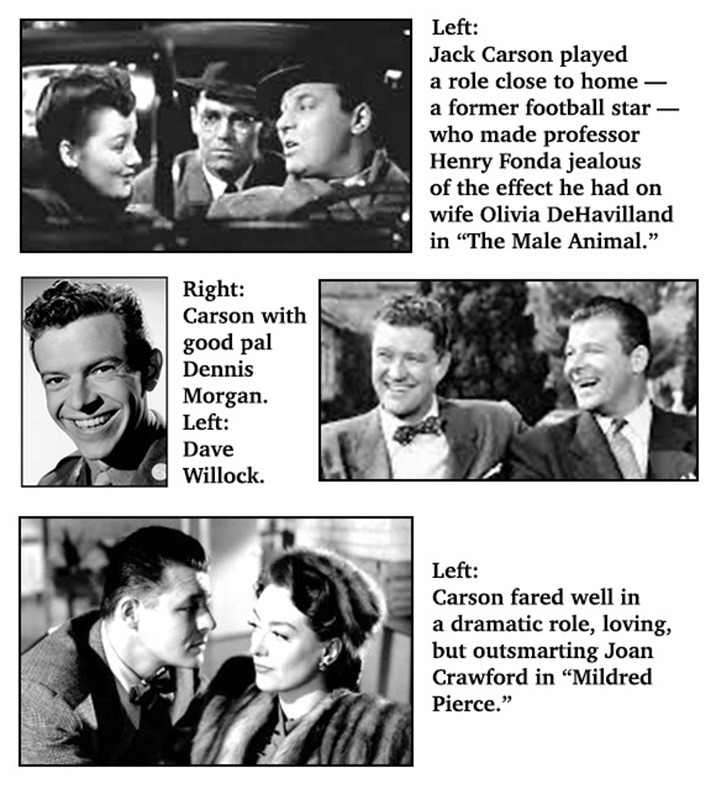

His first battle was in the office of Jack Warner 12 years ago when Carson was under contract to Warner’s Hollywood studio. In those days, carson was known as the guy who made jokes while Dennis Morgan sang to the girls in a series of romantic musical comedies. The team of Carson and Morgan is perhaps best rememberd for “Two Guys from Milwaukee” and “Two Guys from Texas.”

“I told Warner I wanted some good roles,” said Carson. “I said if he’d let me do one worthy picture every year, I’d do anything else he wanted me to.”

THE DISCUSSION ended when Warner gave Carson a release from his contract.

“He said I’d come crawling back to him, but I proved him wrong,” Carson bragged.

Morgan wasn’t so successful.

The two men are as close off-camera as they were during their movies, so Carson was interested when Morgan carried his battle into Warner’s office.

“Dennis had a contract that called for two pictures a year at $150,000 per picture. That was quite a salary in those days,” Carson said. “The studio asked Dennis to make one picture for $175,000 and forget about the second one every year, but Dennis said no. Warner fixed him buy giving Dennis a 12-day shooting schedule on the next film. Then the studio allowed him eight days . . . then just five. All three pictures were terrible; Dennis’s career was ruined.”

Morgan salvaged part of his contract and still receives some money from the Warner Brothers studio, but he hasn’t made a Grade A movie in several years.

ON THE OTHER HAND, Carson claimed he’s just where he wants to be.

“I can turn down parts I don’t like and accept other roles that don’t seem as lucrative.”

Thus when Carson accepted the Canal Fulton engagement, his friends said it might not be a wise decision.

"They said Canal Fulton had only 633 seats, or something like that, but I told them I wanted to do the show. That’s what I mean about my position — I pick parts now, not money.”

CARSON, 52, HAS BEEN acting since his undergraduate days at Carleton College in Minnesota. His size — six-feet-two-inches, 210 pounds — made him a football hero, but it also helped him land a part in his first campus play. He was cast as Hercules.

Carson’s stage debut showed he was still more of a football player than an actor. During his dramatic exit in the first act, he tripped over another actor and pulled down the set.

The laughs that followed convinced Carson to try comedy, and so he teamed with classmate Dave Willock and they went into vaudeville. (Willock is featured this season on the “Margie” television series.)

When vaudeville died, Carson went West to make movies. He made an impressive start as a supporting player, but found himself in the silly comedy rut.

He broke out in 1950 and has since dones some serious roles — “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” for one — and now considers himself a versatile performer.

“My career has gone up and down about four times,” he said. “Each time I seem to come back a little stronger than before.”

|

|

Besides interviewing him, I went to see him perform at Canal Fulton, where he did something that probably violated the rules of theater and possibly upset other members of the cast, but the audience loved it.

"Make a Million" was not a particularly good comedy, but the appeal of summer theater at Canal Fulton and many other places around the country was the big name star who came into town for a week. The star was performing a certain play every week in a different location, and it was up to each resident company to prepare to be featured in several different plays and musicals during the three-month season.

Carson and his Canal Fulton castmates were about 10 minutes into their opening night performance when two ladies arrived and began looking for their seats. Carson stopped the show, and walked over to the section where the ladies were seated. The small stage was in the center of the theater, so the performers were fairly close to everyone in the audience.

He told the ladies, "You're probably wondering what has happened in the play so far . . . " And he proceeded to bring them up to date, and did it in entertaining fashion. When he reached that point where the latecomers arrived, the turned toward his castmates and resumed the production.

Carson began his movie career in 1937 with an uncredited performance as a gasoline station attendant in "You Only Live Once." As a Warner Brothers studio player, he appeared in 14 films that year. If you watch old films — and I watch a lot of them — Jack Carson seems to be in all of them. (If he isn't, Ward Bond is.)

You have to pay attention to catch him in some of the films, but his list of screen appearances include "It Could Happen to You," "Stage Door," "Bringing Up Baby," "Vivacious Lady," "Mr. Smith Gos to Washington," and "Enemy Agent." He had bigger roles in "The Strawberry Blonde," "The Bride Came C.O.D.." "Gentleman Jim," and one of my favorites, "The Male Animal" with Henry Fonda and Olivia deHavilland.

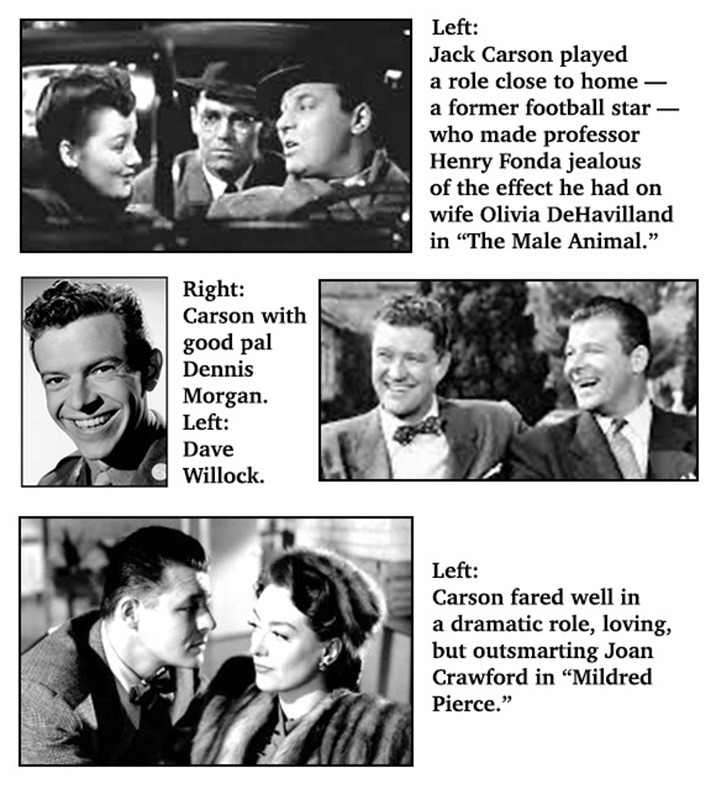

"Roughly Speaking," another favorite, was followed by "Mildred Pierce," and while Joan Crawford won an Oscar for the film, it's Carson who delivers perhaps the best performance. He helped usher Doris Day into film with "Romance on the High Seas," made a few comedies with his buddy, Dennis Morgan, and went all dramatic in "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" in 1955.

He died a year after I interviewed him. He was only 52 years old.

Carson was often the best thing in his movies, but I think he was taken for granted much of the time. And while this may not be a measuring stick for greatness, no one — repeat: no one — could do a double-take as well as Jack Carson. |

|

| |

|