Providence Journal, August 17, 1969

By JACK MAJOR

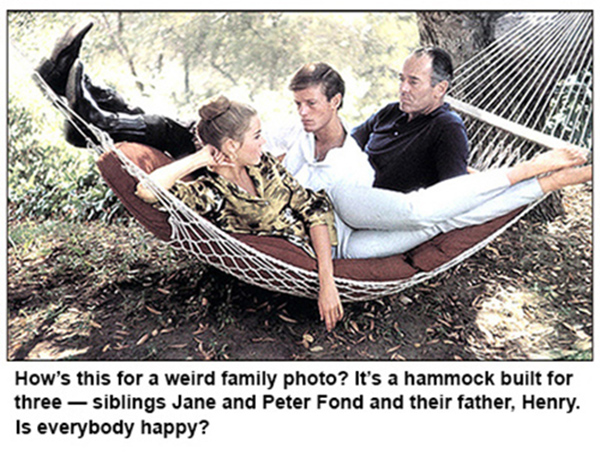

Peter Fonda is tall and skinny and dresses like a member of Hell’s Angels who went straight. Girls think he’s sexy and guys think he’s cool. Movie critics think he’s a bad actor and folks who like to put other people into categories say Fonda is a spokesman for the young generation.

He was in Providence recently to promote “Easy Rider,” a film he wrote and produced. He’s also one of its stars. The film is so successful that critics are eating their words about Fonda. Well, most of their words. Fonda’s acting is still being panned by reviewers, but he’s finally receiving credit for being serious about his work and for helping to turn out one hell of a movie.

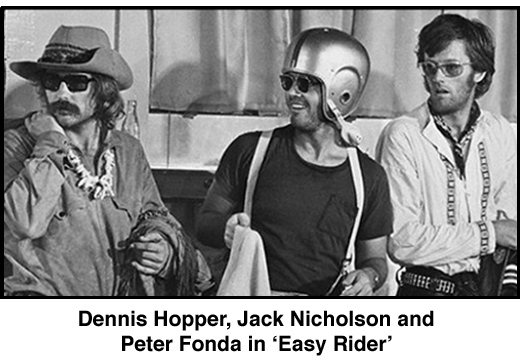

When he set out to make “Easy Rider” with a couple of friends, Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson, the reaction around Hollywood and New York was “So what?” Fonda went into the project with a reputation as a foul-mouthed, outspoken young man who had made incredibly bad films for other people. And a brief description of his own project made it sound like just another motorcycle flick – Fonda had already done a couple for American-International Pictures – and if there was one thing the movie industry didn’t need it was another “Hell’s Belles Turn-On The Wild Bunch at Dragstrip Beach.”

Fonda claims the idea came to him while he was in Toronto two years ago to drum up publicity for “The Trip,” a Hollywood attempt to exploit LSD’s popularity, which probably peaked in 1967. “I went to a banquet and heard Jack Valenti speak,” recalled Fonda. (Valenti is the president of the Motion Picture Association of America.) “Valenti said he was tired of cheap films about drugs and motorcycle gangs. He paid homage to the big budget movies. Like the answer to all our problems was another ‘Mary Poppins.’ That’s when I decided it was time to make a cheap motorcycle film.”

But, of course, Fonda regards “Easy Rider” as much more than that. He puts down the film only when a pretentious movie critic reads into it more than there really is. “Whenever someone over analyzes ‘Easy Rider’ and asks me if his interpretation of the symbolism is correct, I say, ‘What symbolism? ‘Easy Rider’ is just another motorcycle flick.’ ”

But there is symbolism in “Easy Rider.” “We talk about the American Dream,” said Fonda, “and it’s all about how people talk about what’s right and what’s wrong. ‘Easy Rider’ tells ‘em they’re all screwed up. And the character I play is Captain America. Now that’s got to be symbolic, right?”

Reviewer Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times described “Easy Rider” this way:

“The central difference – though there are several – between this and earlier bike pictures is perhaps simply that the earlier riders – for purpose of drama as much as anything else – were cast as men of violence, or, at least, as men quick to meet with violence the violence they triggered around them. But Fonda, Hopper and their new-found co-rider Nicholson are non-conforming but unassertive men of peace adrift in a society they find conformist in its violent fear-hatred of their easy unorthodoxy.”

Captain America and his two buddies represent a threat to the status quo, and such threats have to be eliminated. That’s how Fonda sees the average American mentality on such matters, and his film is not a pretty story with a pat conclusion. It’s merely a look at things the way they are. Most of the performers are real people who “behave” rather than “act,” and Fonda is only inviting us to share that look.

Besides making a statement, ‘Easy Rider” provided Fonda with an interesting challenge: to refute Valenti’s argument that super colossal big budget projects are a necessity. “Easy Rider” was made for the ridiculously low price of $375,000, which on an average Hollywood production probably wouldn’t cover the leading actor’s bar bill.

“Of course, for $375,000 I had nothing to lose,” said Fonda. “If ‘Easy Rider’ didn’t turn out the way we hoped, we could always treat it as another motorcycle flick and break even at the box office. All we have to do is put up a picture of me driving a bike across Texas and kids will come to see the film.”

Fonda is taking success in stride, admitting he was fantastically lucky the film turned out as well as it did.

One break was that Dennis Hopper’s directing worked so well. “I’ve known Dennis for years and he’s a good friend of mine. I thought he could do a good job,” said Fonda.

To others, however, Hopper was a serious risk, a method actor’s method actor who had little to show for his 10 years in Hollywood except a pouty face and a passable imitation of the young Marlon Brando.

Jack Nicholson returned Fonda’s favor with a performance most critics termed “brilliant.” “I admit Jack surprised me,” said Fonda. “I knew he could act, but I didn’t know how well.”

Little bits fell into place with unexpected ease. A cameo appearance by record producer (and boy millionaire) Phil Spector turned out perfectly.

Brief performances by unknowns Toni Basil and Karen Black were delivered flawlessly, and the real people caught on camera across the Southwest and the South came across as real people on film. “They weren’t intimidated by the 'Lights! Camera! Action!' bit."

Fonda’s mission now is to generate interest in the film. I asked why he was taking time to tour the country when “Easy Rider” was getting so much good publicity on its own.

“I’m trying to reach people who otherwise wouldn’t see a Peter Fonda film.” He’s referring to Mr. Average American who thinks everything is just fine and that if we do nothing about it things will become even finer.

“And let’s be honest,” Fonda continued, “I wrote the film and didn’t take any money for it. I produced the film and didn’t take any money for it. And I acted in the film and didn’t take any money for it. Other people are making money from it, and now I want to. And the only way I will is if the film makes a big profit because I’m working on a percentage basis.”

Fonda’s not looking to get rich, necessarily, but he’d like to be able to make another movie statement, and then another, and another.

Fonda’s problem, much of the time, is that while he says a lot, he is understood very little. He had a disagreement with Bob Dylan, who composed one of the songs featured in “Easy Rider.” Dylan took his name off the song because he didn’t like the movie.

“He told me we should have dropped the downbeat ending and replaced it with a message of hope,” said Fonda. “We argued the point awhile and finally he said, ‘You just don’t understand what I’m trying to say,’ and I told him, ‘It’s you who don’t understand what I’m trying to say.’ ”

Fonda has this difficulty, in part, because his background is strictly establishment-oriented, his appearance and behavior is strictly New Left, and his thinking is somewhere in-between. He likes to hit people with strong statements to wake them up, but this sometimes makes people turn him off instead.

He recalled an appearance on television’s “The Dick Cavett Show” when the discussion got around to violence and murder and capital punishment. Fonda came out against capital punishment and offered this as an alternative: “Make people eat what they kill.” The idea shocked the audience, and it was meant to. “Sure, it’s a gruesome idea, but think about it awhile. If you’re looking for a deterrent to murder, this is it.”

Such statements have added to Fonda’s image as a weirdo. Actually, he seems like a bright, extremely personable guy who knows how to win friends. Certainly he’s a million miles from the “nice” Peter Fonda who broke into movies in “Tammy and the Doctor.”

“In those days I was convinced the thing to do was earn a lot of money as quickly as I could so I could retire. Then I woke up to what was happening. I began asking questions, trying to discover why things are the way they are. I started to change. I found there are more important things than just making money. But I’m not one of those guys who makes excuses for what I used to do. Sure, I make fun of ‘Tammy and the Doctor,’ but it was my picture. I can’t hide that fact. Hell, all you have to do is watch The Late Show. There it is.”

Now Fonda is a rebel. Gone is the colorless, plastic face Hollywood tried to give him. And he comes across with such things as “ 'Hope,' to me, is a negative word. I don’t think people should have hope.” And people back off because they’d sooner give up smoking than give up hope.

“ 'Try' is another negative word,” said Fonda. “Suppose I said, ‘I’ll try to be there for the interview.’ That’s negative because it leaves you in the air. ‘I’ll be there.’ That’s positive. 'Try' or 'hope' merely postpone things. Just like 'choice.' We shouldn’t have a choice about putting the Bill of Rights into practice. We should do it. We shouldn’t have a choice about going to war. We just can’t do it. We shouldn’t have a choice about improving our prisons. We just have to improve them. And is there a choice about ending water pollution?”

And Fonda hits you with “I’d like to overthrow the government.” No, Captain America isn't a Communist. He continues:

“I’d like to overthrow our government, but not our system of government. In other words, the men who represent us are our government, but do they truly represent us? I say we should vote in a whole new bunch of people. That would be overthrowing the government. I know one thing: if my agents weren't doing the best possible job for me, I’d overthrow them and get someone else.”

This story, because it appears in an aboveground, family newspaper, distorts a picture of Fonda, whose speech is full of four-letter words we cannot repeat. Fonda is one of those people who uses such words well. From him they sound appropriate.

“There’s only one dirty word I know,” he said, “and that word is ‘security.’ Terrible things happen to people who find security. They become fat, lazy and complacent.”

Fonda denied he speaks for any group. “People accuse me of representing the young generation. I speak for no one but myself, and I know I speak in generalities, and I know I have no answers. I’m just trying to create questions. As soon as you give people answers, they stop thinking.” |