| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

|

|

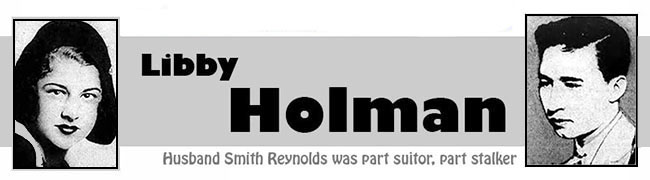

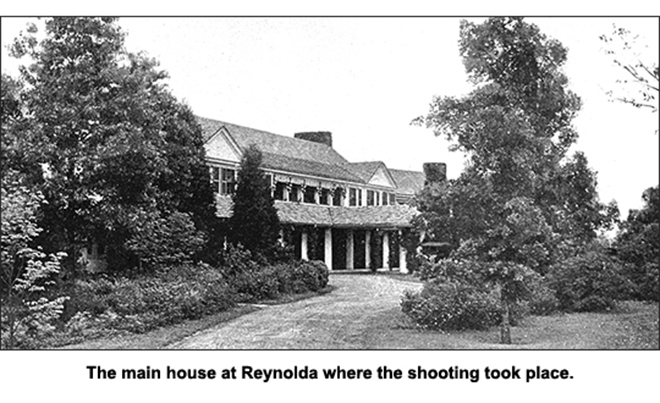

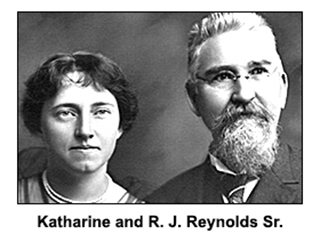

By JACK MAJOR So it was with bisexual singer Libby Holman, whose puzzling definition of love landed her in a mess that left her first husband with a bullet through his head and derailed her once-promising career. Holman's disastrous first marriage — there would be two more — was far too messy to be wrapped up in just one song. Perhaps not even in an Italian opera. The 1933 news story above marked a new chapter in the soap opera that was Libby Holman's life. A home-wrecker in 1931, a murder suspect in 1932, in 1933 she became mother of a premature baby who was struggling to survive. It was as close as Holman would get to playing a sympathetic role. The death of her fuzzy-cheeked, moody, millionaire husband was one of 1932's big stories. Exactly what happened remains a mystery. The forensic evidence, such as it is, can be used to support several theories; witness statements were changeable and often contradictory. The case inspired three movies, most famous of which is "Written on the Wind," a 1956 release based on a 1945 Robert Wilder novel of the same name. However, that film's three leading characters, especially because of the actors chosen to play them (Lauren Bacall, Robert Stack and Rock Hudson), bore little resemblance to their real-life counterparts. Another cast member, Dorothy Malone, won an Oscar as best supporting actress, playing a character who was entirely fictitious. The film was set in Texas, but the real drama unfolded in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, at Reynolda, an estate built for R. J. Reynolds, the tobacco baron, who unfortunately died a few months after the home was completed in 1917. (I assume the family pronounced the estate's name "Ray-NOLD-ah.") R. J. Reynolds had two sons and two daughters. The oldest child, R. J. Reynolds Jr., was 11 when his father passed away. His youngest, Zachary Smith Reynolds, was only six. The children would lose their mother in 1923. Both sons were spoiled, had no ambition to work at their father's company, and received allowances large enough to cover the expense of every whim. AT THE TIME of their secret wedding – on November 29, 1931 — Libby Holman was 27, but had an air about her, thanks living several years in New York City, performing in Broadway musical, and being a celebrity, at least, in The Big Apple. People may have been misled into thinking she was mature for her age. The fact she married Smith Reynolds (his first name was seldom used) was an indication she either was the scheming gold-digger many people suspected ... or was just as confused about love as he was. Smith Reynolds was 20 years old, going on 13. A film of their romance might star Angelina Jolie and Justin Bieber. Holman and Reynolds did not make public their marriage until May, 1932. Two months later her husband was killed by a bullet from his Mauser .32-caliber pistol. Libby Holman remained in the headlines for the rest of the year as authorities tried to determine whether Reynolds had committed suicide or whether he had been killed by his wife, with help from 19-year-old Albert "Ab" Walker, a lifelong friend of the victim (and the character played by Rock Hudson in "Written on the Wind"). Like Reynolds, Walker also appeared younger than he was. In stories, he comes across as a rather pathetic hanger-on, faithful to his friend and boss (Reynolds), but smitten with his friend's wife. Walker, a logical suspect in the shooting, tampered with most of the important evidence. And he had plenty of time to tamper — almost six hours elapsed between the time Reynolds was shot and the police arrived. In that time, Walker drove Mrs. Reynolds and her dying husband to the hospital, spent time alone with her in a private room, returned to the mansion, cleaned the room where the shooting occurred, and took the gun (which he later put back while no one was looking). IN ADDITION to his wife, the victim had one other love — flying. He started when he was 15, and flew as much as he could. He had at least one plane of his own, and used it to court Libby Holman when she was on tour in a musical. One big problem: When he began chasing Holman, after seeing her onstage in Baltimore, he was only 18 — and married. Oh, yes, his wife was pregnant. One wonders what his father would have thought had he lived into the 1930s. R. J. Reynolds Sr. was about as different from his youngest son as two people could be. For one thing, R. J. Sr. remained single until he was 55. He was too busy making money the old-fashioned way — through his own initiative and lots of hard work. (He was uncle of Richard S. Reynolds Sr. of aluminum foil fame.) Born in Virginia in 1850, Reynolds Sr. left home, bought a tobacco farm near Winston-Salem, and struck it rich with his Camel cigarettes. Among his Reynolds married Katharine Smith in 1905 and died of pancreatic cancer in 1918. His widow, 30 years his junior, remarried, but died in 1923. Surviving their mother were R. J. "Dick" Reynolds Jr., who was 17 in 1923; sisters Mary, 15, and Nancy, 13, and Zachary Smith Reynolds, 12. All four children went to live with their uncle, William Neal Reynolds. Or perhaps their uncle and his wife moved into Reynolda, which would have made more sense. Smith Reynolds' sisters married a few years later and his big brother became a globe-trotter. Richard J. "Dick" Reynolds would live long enough to chalk up a few accomplishments — he briefly was chairman of his father's company and also helped launch Delta Airlines — but he began his adult years as a playboy and ended it as a disgruntled parent who disinherited his six sons. In 1929, while driving an automobile in England, Dick Reynolds struck and killed a pedestrian and served a five-month jail term. An Associated Press story about his return home said his "escapades in the past have several times had him in the limelight." While living in New York City when he was 21, he disappeared, touching off a nationwide search. He was found a few days later in St. Louis where, he said, he had gone to have dinner. As a teenager he ran away from home to work on a tramp steamer. Younger brother Smith Reynolds was considered headstrong, but pleasant. His love of flying at a time plane crashes were daily occurrences, made it unlikely he'd enjoy a long life. However, what doomed him were emotional problems that surfaced during his affair with Libby Holman, and, more tragically, after their marriage. Admittedly, the only two people who went into detail about these problems later were murder suspects Libby Holman and Ab Walker, who claimed Smith Reynolds had often threatened suicide. Reynolds' other friends and relatives said that was news to them. Which gets us back to a puzzling question — if Libby Holman really knew Smith Reynolds as well as she said she did, how could she ever have agreed to marry him? The obvious answer was money, and perhaps her certainty he wouldn't be around too long. |

LIBBY HOLMAN was born Elizabeth Holzman in Cincinnati on May 23, 1904, to a Jewish couple, Alfred and Rachel Workum Holzman. Her father was an Ohio-born lawyer, whose family probably emigrated from Germany like many others who settled in Cincinnati. It was her father who dropped the "z" from his last name, perhaps to disguise his ethnic origin. (Smith Reynolds' relatives would refer to Holman as a "Jewess," perhaps harboring prejudice; one piece I read said the singer herself had nothing but disdain for her Jewish heritage.) According to her biography on imdb.com (Internet Movie Database), Holman's family was wealthy until 1904 when an uncle embezzled nearly $1 million, "leaving her innocent father scandalized and bankrupt." Stories about her early life vary on a few important points. Some accept Libby Holman's lie that she was born in 1906. That makes it difficult to believe she was a college graduate at the age of 18. Wikipedia has her graduating from the University of Cincinnati at the age of 19, then moving to New York City. From there she was offered a role in a touring company of "The Fool," a play by Channing Pollock, who advised her to pursue a career in the theater. The imdb.com biography doesn't say how or where she joined the cast of that play, but indicates she was still a college student at the time, and that Pollock advised her to drop out of school and become an actress. No story says what seems obvious — that Libby Holman had decided at an early age to become a stage actress. She also must have been a singer, too, though journalists reported her voice was changed by a botched tonsillectomy. One version of this story claims Holman believed the operation had ruined her voice. IN ANY EVENT, she left Cincinnati and headed for New York in 1923 or '24. In 1925 she was on Broadway in the supporting cast of "The Garrick Gaieties," the first successful musical for Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart. Her next show, "Merry-Go-Round," in 1927, was a flop, but she attracted attention for her rendition of a song called "Down in Hogan's Alley." A year later she was cast with Brian Donlevy and Charles Ruggles in "Rainbow," which featured music by Vincent Youmans, lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, with Max Steiner as the musical director. It couldn't miss ... but it did (though it was turned into a John Boles-Joe E. Brown movie operetta, "Song of the West," in 1930, in Technicolor yet). Holman bounced right back — into another flop, "Ned Wayburn's Gambols," in January 1929. She was now discouraged enough to consider going to Hollywood, even though she had another Broadway offer. Some stories say she was set to board a California-bound train until her friends convinced her to stay in New York and accept a starring role in "The Little Show" with Clifton Webb and Fred Allen. HOLMAN BECAME became an overnight sensation in that show with her singing of "Moanin' Low," and what was termed "a torrid dance" with co-star Webb. (Anyone who remembers the characters Webb went on to play in movies — "Laura," "Mr. Belvedere Goes to College," "Cheaper By The Dozen," etc. — might snicker at the word "torrid," but in his younger days Webb apparently was quite good in musicals and had an excellent singing voice.") "Moanin' Low" became one of her signature songs, the other being "Body and Soul," which she introduced in her next show, "Three's a Crowd," also with Webb and Allen. (Today people are more likely to associate "Moanin' Low" with actress Claire Trevor, who sang it during her Oscar-winning performance as a washed up, alcoholic singer in the 1949 film, "Key Largo.") When 1931 began, Libby Holman was as successful as she would ever be. Her singing, delivered in an unusually deep voice, was considered soulful, exotic and strongly influenced by Negro spirituals. It was rumored that she was mulatto — half white, half black — but that may have come from misconceptions that exist even today. African-Americans aren't the only people who sing the blues. (They certainly have nothing on the Irish.) As for the botched tonsillectomy, it's more likely she simply worked with the tools she was given at birth. (One of her songs available online, "My Man Is On the Make," from 1929, is not especially deep or soulful. Years later no one felt it necessary to explain why Marlene Dietrich's voice was so low and husky when she crooned "Falling in Love Again." In other words, Libby Holman's voice probably was what it was; no explanations or labels required.)

Holman, the singer, developed a cult-like following after the Reynolds tragedy detoured her theater career. There are several Holman songs that can be sampled online, including a 1940s version of "House of the Rising Sun," which is a test for the listener. Anyone who can make it through the entire song qualifies for the Libby Holman fan club. Her ver ... sion ... is ... ex ... cru ... ci ... at ... ing ... ly ... slow. I've read her performances were inconsistent; she often sang off-key. HER PRESS AGENTS concocted an interesting biography that was regurgitated by many journalists. In addition to subtracting the two years from her age, it says she moved to New York City to study the French literature, that singing was an afterthought, that she was an "omnivorous reader," that people were impressed by her intellectual curiosity and that she once said her greatest ambition was to assemble at her home the world's greatest minds for a mutual exchange of ideas. I presume she also longed for world peace, was a gourmet cook and enjoyed long walks on the beach. On May 23, 1931 Holman celebrated her 27th birthday, even if there were only 25 candles on her cake. She was single, had never been engaged nor even rumored to have a serious relationship (except for one columnist's ridiculous suggestion she was about to marry Clifton Webb, who lived with his mother — and would do so until she died in 1960, when he was 70 years old). Holman also was described as almost unique among young female Broadway stars in that she wasn't self-conscious about appearing alone in public. SHE ALSO wasn't self-conscious about her relationship with lover and advisor Louisa Carpenter Jenney, a lesbian who wasn't above marrying a man, if for no other reason than to borrow his clothes.

Though his wife was pregnant back in North Carolina, Smith Reynolds spent much of 1930 chasing Libby Holman from city to city in his airplane. When her tour was over and she went to work on "Three's a Crowd," Reynolds became a fixture on Broadway and became known as "The Millionaire Kid." Reynolds would take Holman up in his plane to see the sun rise over New York. Smith Reynolds was an impetuous kid. It was on November 16, 1929, a few days after his 18th birthday that he and Anne Cannon, daughter of Joseph F. Cannon, the millionaire towel manufacturer from Concord, North Carolina, eloped to York, South Carolina, referred to as that state's Gretna Green, after the Scotland village famous for runaway weddings. The couple was driven to York by the Cannon family chauffeur and accompanied by the bride's father, Joseph F. Cannon, who didn't bring along a shotgun, but may have anticipated the need. (Anne Cannon Reynolds II, was born August 23, 1930 — nine months and one week after the wedding.) WHATEVER PASSION had fueled the Reynolds-Cannon courtship quickly evaporated after vows were exchanged. Months later, when Reynolds began stalking Holman, his wife shrugged it off and resumed a social life of her own, though still technically married. In December, 1930, four months after giving birth, Anne Cannon Reynolds was escorted home from a cocktail party by Tom Gay Coltrane, son of a banker. Two hours later, Coltrane was found dead under a hedge. The coroner's jury ruled Coltrane had died from acute alcoholism, aided by a fall and exposure. According to the Holman's imdb.com biography, Louisa Jenney encouraged her friend/lover to marry the kid with the airplane because he had an endless supply of money. So when Reynolds proposed, Holman said yes and declared her undying love. The insecure young man would beg her to repeat that pledge almost daily. But first, he needed a divorce, so nice young man that he was, Smith Reynolds flew his wife to Reno, where their marriage officially ended. Anne Cannon Reynolds went along with this because she wanted a divorce as much as he did. She, too, was already engaged. SHORTLY AFTER Reynolds dropped his first wife off at a Reno hotel, he did something that should have given Libby Holman pause. He phoned her and again asked if she really intended to marry him ... because if she didn't, he would kill himself. At least, that's what Holman would testify after his death. The divorce became final in November, 1931. Within days Anne Cannon married Brandon Smith, and Smith Reynolds married Libby Holman. The latter wedding took place in Monroe, Michigan, on November 29, 1931, but would remain a secret until May 12, 1932, when the couple arrived in New York City and she registered at the Ambassador Hotel as Mrs. Smith Reynolds. The New York Times took note and spilled the beans. Holman told the Times the marriage took place in Hawaii in April. It was a lie easily believed because she and Reynolds had pretty much led separate lives during the first part of 1932 — she was on tour and he was flying around the world or aboard a ship that carried his plane across an ocean. Reynolds may have been impetuous, but apparently he wasn't about to risk flying from California to Hawaii. And it was in Hawaii that he and Libby were reunited in April, 1932, and it was from Hawaii that they returned to New York. From New York, they flew to Winston-Salem to spend the summer at Reynolda, where Smith Reynolds reigned as king. Sadly — and mysteriously — the king would soon be dead. |

Libby Holman and her husband had the place to themselves, except for a household staff, which included a superintendent, Stewart Warnken. Reynolds' Uncle William lived nearby, but his two sisters, both married, lived out of state. Brother Dick (R. J. Reynolds Jr.) was off on one his jaunts, probably in Europe. Some of Holman's New York friends visited Reynolda, each apparently making a bad impression on the locals, who bristled at tales of loose morals and derogatory remarks the Yankees were making about the Carolinas. People who live in New York City tend to feel superior; entertainers and athletes who work there tend to attract more attention than they deserve. Holman's friends included many homosexuals, which displeased the locals. Days before the fateful event, actress Blanche Yurka arrived at Reynolda, but hers wasn't entirely a social visit. Reportedly she was giving acting lesson to Libby, prepping her for a dramatic role that fall. Also arriving in June was R. Raymond Kramer, a young man who tutored Reynolds in mathematics because Libby's husband, at the urging of his wife, planned to enter Guggenheim Aeronautical School at New York University in September to prepare for a career in aviation. |

|

|

|

WHEN HOLMAN awoke on July 5, she was suffering the effects of a July 4 party. Facing her that evening was another party, this one to celebrate the birthday of one of her husband's friends, C. G. Hill. Holman would later claim she had little recollection of either the July 4 party or the one the next night. She also would claim she had nothing to drink at either party, which likely was not true. She did recall giving her husband some important news on July 5 — she was pregnant. The stage was set for one of the biggest stories of 1932: |

|

|

|

Reynolds and Holman had entertained several friends that night, but all of the guests left about midnight, with the exception of Ab Walker and Blanche Yurka. What followed was an inconclusive investigation that included ever-changing stories from Libby Holman and Ab Walker. More than a month into the investigation, Smith Reynolds' body was exhumed on August 23, 1932, and four doctors were brought in to do another autopsy. Their findings indicated the death was not suicide; they ruled Reynolds could not have fired the gun. Emerging as the most accepted story was an argument had broken out after midnight, between the always jealous Reynolds and Holman over her relationship with Walker. She continued to insist to police her husband was often suicidal. Walker supported her story, but the two of them were charged with murder. A few months later the charges were dropped because authorities felt the evidence was insufficient to get a conviction. This decision pleased the Reynolds family, who did not want Holman's baby born in prison, or a trial and an attendant scandal that might negatively affect businesses that bore the Reynolds name. But the Reynolds family couldn't have been pleased with the circumstances under which Christopher Smith Reynolds was born. |

LIBBY HOLMAN left North Carolina, and was living at Louisa Jenney's estate near Wilmington, Delaware. On January 9, 1933, Mrs. Reynolds was driven to Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia by Mrs. Jenney, who dressed, as she often did, in man's clothing, and at the hospital was mistaken by many as the father-to-be. Holman's baby wasn't expected for two months, but, on January 10, he arrived. Despite his premature birth, the baby responded well to life in an incubator. Mother and child remained in the hospital until April, and plans were made for the inevitable legal battle to establish the child's claim to a portion of the tobacco fortune that had been set aside for Smith Reynolds. After much wrangling, the child was awarded several million dollars in a trust, and his mother was given $750,000. The final settlement, in 1935, was made after an interesting assertion by Joseph F. Cannon, the millionaire towel maker and father of Anne Cannon, the first Mrs. Smith Reynolds. Cannon, in an attempt to secure a greater share of the Reynolds inheritance for his daughter, and to have Christopher Reynolds and Libby Holman excluded, claimed his daughter was doped with morphine and "physically and mentally unable" when she signed her Reno divorce deposition in 1931. Cannon thus insisted the divorce was invalid and that his daughter was the one and only Mrs. Smith Reynolds. CONFLICTING TESTIMONY was offered about Anne Cannon Reynolds' mental state in Reno in 1932. Interestingly, the doctor who refuted Cannon's claim (saying the young woman was fine and clearly in possession of her faculties), also admitted she was not present at the hearing which finalized the divorce, that she was represented by an attorney. Cannon believed that Smith Reynolds, perhaps with the support of Libby Holman, had engineered a questionable divorce. But Brandon Smith, who married Anne Cannon shortly after her Reno visit (then subsequently divorced her), insisted the young woman knew exactly what she was doing in Nevada. Winston-Salem Judge Clayton Moore (no relation to the actor) decided in favor of a settlement proposed by the Reynolds family. Joseph Cannon, while losing the battle of Reno, should have been pleased — because his daughter was awarded the biggest chunk of an estate valued at almost $28 million. Her share was 37-1/2 percent (about $11 million), with Christopher Reynolds receiving 25 percent, or almost $7 million. Several million dollars were awarded to R. J. Reynolds Jr. and his two sisters for the establishment of a charitable foundation named after Zachary Smith Reynolds. LIBBY HOLMAN spent most of the next six years virtually married to Louisa Carpenter Jenney. She also returned to the Broadway stage in November, 1934, as a star of "Revenge With Music," a musical by Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz. The show, set in Spain in 1800, ran 158 performances, but was considered a failure. Highlight was provided by Holman with her rendition of "You and the Night and the Music." She worked at nightclubs, but for many years was regarded more of a curiosity than entertainer. In the fall of 1938, she was reunited with Clifton Webb in a Cole Porter musical, "You Never Know," one of Porter's lesser efforts. (It folded after 78 performances.) Also in the show were Toby Wing and Lupe Velez known as "The Mexican Spitfire." There was instant dislike between Holman and Velez, then the wife of Johnny "Tarzan" Weissmuller. Velez so hated her bisexual co-star that she threatened to kill her. While she and Louisa Carpenter Jenney lived together much of the time, Holman also had relationships with men, among them actor Phillips Holmes, who was homosexual. (The word "gay" hadn't yet been misappropriated.) Holman then decided for whatever reason to marry Holmes' actor-brother, called "Rafe" though his name was spelled "Ralph." Her new husband, 11 years her junior, may well have been heterosexual, but his wife's reputation was such that people began to assume he was another of her homosexual admirers. The Holmes brothers, both Canadian, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940. Phillips Holmes, by far the more successful of the two brothers, was killed in a training accident in August, 1942. Ralph Holmes survived the war, but was badly shaken by the experience, as well as his brother's death. It didn't help that while he was gone, his wife continued to bounce back and forth between lesbian affairs and involvement with men who were homosexual or confused about their sexuality. Among Libby Holman's victims was actor Montgomery Clift, who was 21 years old in 1942 when he worked with Holman in "Mexican Mural," a play by Ramon Naya. (By all accounts this play, while it received two awards of some sort, was a disaster once it was exposed to audiences. Wilella Waldorf, in a New York Post review, said "It must be admitted, the view from the windows during intermission was far more spellbinding (than the play)." WHEN HOLMES returned to civilian life, his wife told him their marriage was over. A few weeks later, he took an overdose of barbiturates. There was no doubt this time that the husband of Libby Holman had committed suicide. While preparing to dump Holmes, Holman adopted an infant son named Tommy. Two years later, in 1947, she adopted another infant son, named Tony. Each would receive $1 million after her death. Through the late 1940s and into the '50s Holman's singing career remained alive, though mostly in New York City. She found herself in love with writer Jane Auer Bowles, her last name coming from her marriage to homosexual writer Paul Bowles. When it came to love, Holman obviously was turned on by complications. What involvement she had in the life of her eldest son, the child she once called "the most perfect and adorable thing I have ever seen," isn't clear, but for sure she would have much to regret. In August, 1950, while his mother was in Europe, Christopher "Topper" Reynolds was in California with a friend, Steven Wasserman. The two teenagers had gone there to spend the summer working at a gold mine. However, during the first weekend in August, the boys set out to climb 14,496-foot Mount Whitney, then the highest mountain in the United States. They almost made it — but near the top, a rope snapped and both climbers tumbled to their deaths. DURING THE 1950s Holman became involved in the civil rights movement, and in 1960 she married for the third time. Her husband was artist Louis Schanker, her only husband who was older than she — by one year. (Ironically, until then, he was known for having girl friends who were much younger than he.) This marriage also ended by suicide, but it was Libby Holman who took her own life, dying of carbon monoxide poisoning in the front seat of her Rolls Royce on June 18, 1971. She was found by a member of the household staff at Holman's Connecticut estate, called Treetops. Libby Holman never wanted for creature comforts for almost all of her adult life, but there was nothing comfortable about her personal life which often brought misery to those around her. Her career began full of promise, but much of that promise would remain unfulfilled. |

|

|

|

| HOME • CONTACT | |

other early products were several brands of chewing tobacco and Prince Albert tobacco (giving rise to that old joke which had pranksters phoning merchants, "Do you have Prince Albert in a can? You do? Then let him out!")

other early products were several brands of chewing tobacco and Prince Albert tobacco (giving rise to that old joke which had pranksters phoning merchants, "Do you have Prince Albert in a can? You do? Then let him out!") One wonders what Mrs. Jenney thought when Zachary Smith Reynolds, only 18 at the time, became obsessed with Libby Holman in May, 1930, when Reynolds saw her perform in Baltimore where she was in a road company of "The Little Show" after its Broadway run.

One wonders what Mrs. Jenney thought when Zachary Smith Reynolds, only 18 at the time, became obsessed with Libby Holman in May, 1930, when Reynolds saw her perform in Baltimore where she was in a road company of "The Little Show" after its Broadway run.  John Lanier admitted he'd written two letters to Reynolds demanding $10,000 in cash if Mrs. Reynolds was to remain unharmed. Reynolds and his lawyer went to Sheriff Transou Scott, who, in turn, contacted the Department of Justice. A decoy package of bills was used to lure Lanier into a trap.

John Lanier admitted he'd written two letters to Reynolds demanding $10,000 in cash if Mrs. Reynolds was to remain unharmed. Reynolds and his lawyer went to Sheriff Transou Scott, who, in turn, contacted the Department of Justice. A decoy package of bills was used to lure Lanier into a trap.