|

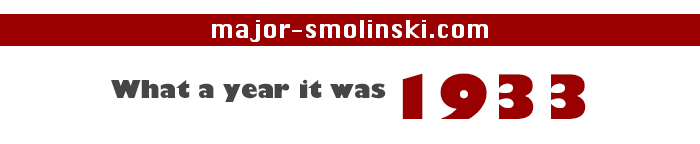

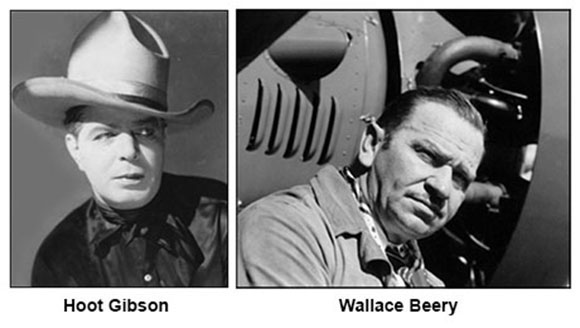

It may have seemed that every aerial stories were divided between those about pilots setting speed or distance records and those about pilots being killed when their plants crashed. However, there was a middle ground, though even stories with happy endings often told of frighteningly close shaves by the people involved, such as two movie stars who loved to fly. (That's one of them, Wallace Beery, with his plane, above.) |

| |

A Pair of Lucky Stars

At least two movie stars were flying enthusiasts. Both had near escapes during the year. Wallace Beery was especially active in the air. On April 15, 1933 he was commissioned a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy Reserve. |

Buffalo Courier Express, July 4

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Hoot Gibson, who rode to fame in motion pictures on a horse, took an airplane today in a special match race at the national air races and wound up in a hospital with concussion of the brain or a possible skull fracture, received in a crash witnessed by 2,000 spectators.

The gray-haired Hollywood actor, long a sportsman pilot, slipped to the ground after rounding the second pylon in a 15-mile race against Ken Maynard, another actor who stars on horseback and spends much of his leisure flying airplanes. The two were flying for a trophy contributed by Will Rogers, film humorist.

Gibson was catapulted from his ship as the motor struck the ground He was unconscious when ambulance attendants dragged him from the ship, but recovered quickly and, with the aid of nurses at an emergency hospital, walked into a dressing room. |

|

|

Syracuse Journal, October 16

ALBUQUERQUE, New Mexico (INS) — Wallace Beery, moving picture star, left Albuquerque for Los Angeles today in a plane piloted by Paul Nantz, Los Angeles aviator, after cracking up his own plane yesterday at the Santa Fe, New Mexico, airport.

Beery encountered a 60-mile-an-hour wind when he attempted to land at Santa Fe. The wind turned his plane around and broke the tip of one wing. Beery was uninjured in the smashup. |

|

|

|

| |

Some fliers who were famous across the Atlantic attracted little attention in American newspapers, even though their situations seem dire, at least briefly. Maryse Hilsz of France received only one sentence of coverage in the Syracuse American on April 2 when her whereabouts was unknown on her flight from France to Japan, which began the day before. However, Hilsz, like Charles Lindbergh, put safety first, and took relatively short hops, landing at the nearest airfield whenever the weather turned against her. She completed her trip on April 16.

The adventures of Lady Mary Bailey, daughter of Derry Westenra, the fifth Baron Rossmore, were more colorful, but she managed to survive her solo flight from England to South Africa, though she made a couple of forced landings along the way. Mother of five children, Mary Bailey seemed a fearless flier, and one who lived a full life, dying at the age of 70.

Also receiving little coverage, at least in the white press, was a flight by two black pilots, C. Alfred Anderson and Dr. Albert K. Forsythe, who flew from Atlantic City, New Jersey, across the county to Los Angeles in July, then later flew back to the East Coast. Dr. Forsythe owned the plane, Anderson did most, if not all of the flying. No black aviators had flown across the country previously. |

|

| |

Syracuse American, July 23

Up, Up, Up They Hope to Go

By CARL L. TURNER

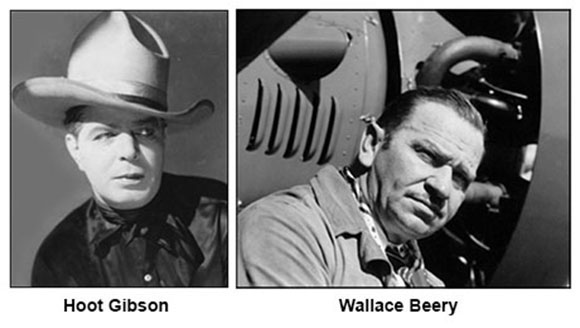

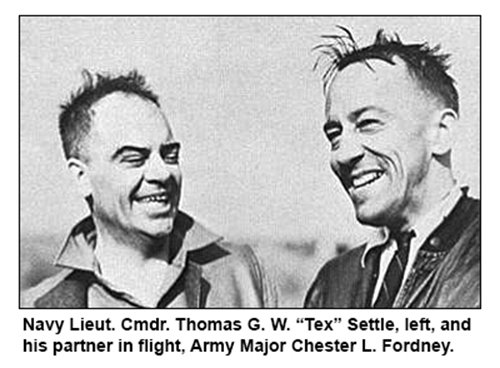

CHICAGO (INS) — The stage was set today for another aviation thriller for visitors at the Century of Progress, an ascent into the stratosphere by Jean Piccard and Lieut. Commander T. G. W. Settle, USN.

The twin brother of August Piccard, Swiss scientist who holds the stratosphere record, and the naval officer who supervised construction of the navy dirigibles, USS Akron and USS Macon, probably will take off from Soldiers’ Field next Tuesday.

Their huge balloon is ready, the airtight metal gondola in which they will live for 24 hours in the region about the troposphere has passed final inspection, and only favorable weather is awaited before beginning the flight.

On several small cylinders of liquid oxygen, Piccard and Settle will stake their lives in the rarefied regions they will penetrate to study the cosmic ray and the weather phenomenon of the upper regions. |

|

The July flight was a miserable failure, but four months later, on November 20, Settle and Army Major Chester L. Fordney set a world altitude record in the Century of Progress stratospheric balloon. What happened after they came back to earth led to an interesting morning for a New Jersey couple (story below).

Jean Piccard and his wife, Jeannette, took off in the Century of Progress balloon in October, 1934, when Mrs. Piccard became the first woman to reach the stratosphere. |

|

|

| |

|

| Imagine you are S. M. Johnson and his wife, in Middle of Nowhere, New Jersey; you just sat down with your morning coffee. Unexpectedly, there's a knock on your door ... |

Syracuse Journal, November 21

Surprise Guest for Breakfast

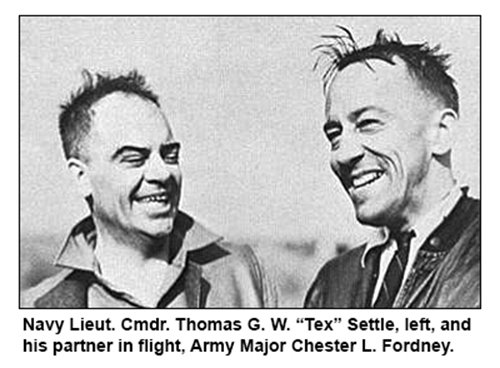

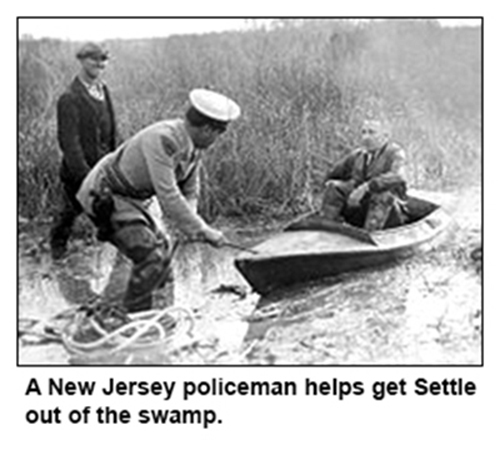

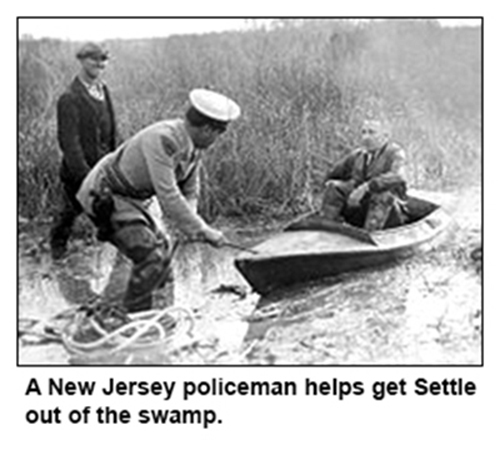

BRIDGETON, New Jersey (INS) — None the worse for their thrilling experience, Lieut. Cmdr. T. G. W. Settle and Maj. Chester L. Fordney were found safe today after they had made a perfect “egg-shell” landing in their stratosphere balloon in the swampy marshes 10 miles southeast of Bridgeton.

They had been missing in their aluminum gondola for hours after having penetrated 11 miles into the sky, and thousands of persons had been searching for them by land and air, with Coast Guard stations making preparation to scour the seas.

“It was a wonderful experience and we wouldn’t have missed it for anything,” said Major Fordney to an International News Service reporter after he had made his way through the marshes at 9:30 a.m. to the farmhouse of S. M. Johnson in the inaccessible Back Neck region.

“I’m Major Fordney,” the visitor said, as he arrived at the Johnson farm. “Fordney the balloonist. Can I use your telephone?”

He was admitted. Without delay he reported by telephone to the Army headquarters in the Sixth Corps area at Chicago. Major Fordney is attached to the Marine Corps, Lieutenant Commander Settle to the United States Navy.

“It was a normal ballooning operation,” said Fordney later. He spoke in a calm, matter-of-fact tone. He is a stocky man of medium height, slightly bald. He wore a sweater over a leather vest.

He said he and Commander Settle landed at 5:50 p.m. They had set out from Akron, Ohio, yesterday at 9:30 a.m.

Instead of trying to make their way through the marshes in the gathering darkness, he and Settle decided to remain in the balloon last night and make their whereabouts known first thing this morning.

Mrs. Johnson, the farmer’s wife, insisted on being a good hostess.”You must have some breakfast,” she told Fordney.

With a smile, the major complied. He admitted he was hungry, even though he and Settle had some concentrated food with them during their flight. He partook of ham and eggs with a relish.

He was casual and smiling when the reporter burst in on the scene.

“Oh, yes,” he admitted, “we did spend a rather uncomfortable night. But the experience was well worth the inconvenience. I worked up a mighty good appetite.

“Our instruments indicated we reached a maximum height of 59,000 feet.”

This was higher than any other Americans had ever penetrated into the sky. The record, 63,320 feet, or 11.8 miles, was established last September by three Russian balloonists near Moscow.

Major Fordney was smeared with mud when he reached the farmhouse after a three-mile trip through the swamp, which was very dangerous. Few persons attempt to cross the marshy terrain without a guide as there have been numerous casualties. Hunters have been caught in the waist-deep mud and have disappeared.

The major’s first consideration was his wife. “Please tell her I’m all right,” he remarked to reporters.

He considered his three-mile walk through the marshes to be a worse experience than his ascent into the bitter cold of the stratosphere.

“It wasn’t much of a job getting here,” he said, “but it was hard work climbing through those bogs and marshes.”

Lieutenant Commander Settle and Major Fordney had dumped their radio-sending apparatus yesterday to lighten their load as they began to descend and drift.

“We came down pretty fast and had to keep dumping things overboard,” said Major Fordney. “When we hit the ground just after dark we found it to be very swampy. So we wrapped ourselves up in the balloon for the night.

“Tex (Settle) stayed with the balloon to guard the instruments, while I walked to the farmhouse. He’s waiting for me to bring him back something to eat.”

The safe landing of the balloon bore out predictions of Navy aviators that Lieutenant Commander Settle would bring himself and his companion safely through. Settle, they pointed out, is one of the Navy’s most competent fliers and consistent winner of balloon races while being the only man in America to hold licenses to pilot anything from a dirigible to a glider. |

|

|

| Balloonists were a hardy bunch. In September the two-man crew of a Polish balloon made a forced landing in the wilds of Canada, 250 miles north of Quebec. They walked along railroad tracks for 50 miles before finding help. The lived on food they found in an abandoned canoe. |

|

|

| |

| Weather was unusually erratic and dangerous in 1933, which accounted for some of the wreckage noted on this page. In August, a whole bunch of pilots headed for a Montreal air pageant. Ordinarily that would seem a safe month. But some of the pilots must have felt their were flying through hell, which is why more than one-third of them turned around and lived to fly another day. |

Syracuse American, August 20

OSSINING, New York (INS) — Pilot Arthur Norwood and his mechanic, L. Newland, one of the 58 planes flying from New York to Montreal, were forced down in the Hudson River opposite here yesterday afternoon. Neither was injured. A hail and rainstorm caused the motor to stall, Norwood said.

The plane alighted in four feet of water and boatmen aided the men to reach shore. The plane was salvaged, but Norwood said he would not resume the flight.

More than one-third of the planes were forced back by the unfavorable weather along the route.

Nineteen returned safely to Roosevelt Field. Another landed in Jersey City; one in Bridgeport, Connecticut; two in Bethany, Connecticut; one in Poughkeepsie, and Arthur Norwood’s plane, which landed in the Hudson River near Ossining. |

|

|

|

| |

| An airmail pilot out of Los Angeles, with his mechanic and three passengers, made an unintended landing in the Pacific Ocean, but luck was with them. |

Syracuse Journal, September 1

Pilot, Passengers Rescued at Sea

MEXICO CITY (INS) — Mack Ayers, air pilot of Los Angeles, was safe today after being rescued at sea.

His hydroplane was forced down 80 miles off the coast while making a regular mail and passenger run from Mazatlan, on the Pacific Coast, to La Pez, Lower California.

The plane, with three passengers and a mechanic aboard in addition to Ayers, was found afloat by pilot of Charles Bucher of a searching expedition. |

|

| Far less fortunate was a Cleveland air mail pilot whose plane crashed in a Michigan swamp when it was blown off course during a flight to Toledo. Harold "Hal" Neff was alive when rescuers found him, but died six days later in a Jackson, Michigan, hospital. |

|

|

| |

| I'm not familiar with Chicago streets, but it must have been a shock to anyone on 65th Street when a Marine Corps plane fell out of the sky. The story doesn't indicate where the flight originated, but one can imagine one of the passengers asking someone on the street, "Is this San Diego?" And the reply, of course, would be, "Not even close!" |

Syracuse American, July 23

Marine Plane Crashes in Chicago

A Marine Corps plane carrying three men crashed at 65th Street in Chicago, two blocks from Cicero Avenue. The plane was headed to San Diego. No one was killed, but one of them suffered two broken legs. |

|

|

| |

| The mass flight of Italian seaplanes that visited the Chicago World's Fair attracted a lot of attention and, in the United States, at least, overshadowed the adventures of a slightly larger fleet of French planes later in the year. The French, however, chose to fly to Africa instead of North America. Both the Italians and the French were attempting to establish themselves as number one in air power and technology. |

Corning Evening Leader, November 8

French Planes Head for Africa

ISTRES, France (AP) — A great French armada of 27 planes, manned by 54 aviators, started a mass flight to darkest Africa early today.

Although 27 planes left here today, 30 will take part in the flight. One reconnoitering machine is already at Perpignan, France, the first scheduled stop, and two at Cartagena.

Of the 15,525-mile flight to French Africa, dangers of desert and jungle will be braved for the sake of France’s military, political, technical and commercial prestige.

The flight is under the leadership of General Victor Vuillemen, desert expert. |

|

| Nationally known columnist Arthur Brisbane clearly believed the French had the edge in air power, though his third paragraph (below), which begins "It is no exaggeration," would have been more correct had he written, "It is a wild exaggeration." |

Syracuse Journal, December 16

Today / By Arthur Brisbane

The French “black squadron” of 28 army fighting planes is flying back from North Africa across the Mediterranean to France.

This is not particularly good news for Mr. Hitler or anybody who objects to French domination of Western Europe. If a “black squadron” of 28 planes can fly over the Mediterranean Sea and far over Africa on a “test flight of inspection,” lasting weeks, what could one or two thousand of the gigantic French air fleet do on a different kind of flight to the cities of an enemy country?

It is no exaggeration to say that if France declared war on any country of Western Europe in the morning, all the cities of that country could be laid waste the same evening. |

|

Brisbane overestimated the impact of bombing and underestimated the spirit and determination of civilians being bombed, as the British, in particular, would prove during World War Two.

Brisbane also disregarded fuel considerations. None of the planes that impressed him so much in 1933 was required to turn around and go back to the airfield where their flights had originated.

Besides, the French clearly had no stomach for war. Neither did England, at the time. The Italians? That was another story, though it should have been obvious to everyone that Germany posed the greatest threat to Europe. And it was Germany that was working on solving the airplane refueling challenge, though doing it in the name of improving mail service across the Atlantic. |

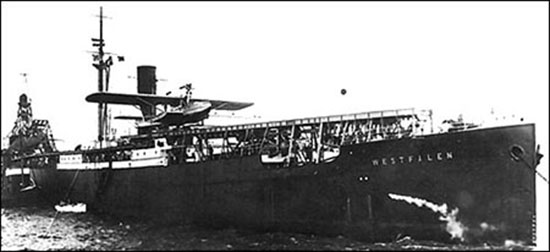

Syracuse Journal, November 1

LAS PALMAS, Canary Islands (INS) — Arriving here safely on a flight from Cadiz, Spain, Robert Untucht, German pilot, today completed the first stage of a flight to South America which will make use for the first time of a mid-Atlantic refueling.

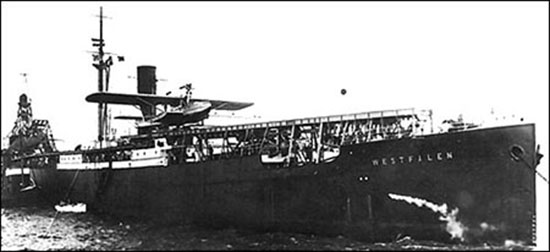

After leaving Las Palmas, Untucht plans to refuel his plane in mid-Atlantic with the aid of the German steamer Westfalen, anchored along his route. Converted into an airplane mother-ship, the Westfalen (photo below) has been equipped with a catapult, from which Untucht will take off when he has refueled his craft. |

|

|

A week later Berlin announced the successful completion of a trans-Atlantic flight with a mid-ocean stop for refueling. The plane refueled, however, was not piloted by Robert Untucht, but by Kramer von Clausbruch in a Dorner-Walflying boat carrying a crew of three men and one passenger. |

|

|

| |

It didn't come as a big surprise to learn that in the early days of airplane travel, the Buffalo Airport was closed during the winter. That changed in 1933, though precautions were taken. American Airways (later American Airlines) assigned its most experienced, bad-weather pilots to fly to Buffalo and beyond.

The company also built emergency fields for planes that had to cut their flights short because of weather conditions.

In late November a sleet storm forced an American Airways pilot to do just that, landing on an airstrip near the small villages of Nunda and Mount Morris. The airline responded by sending automobiles to pick up the 14 passengers and transport them the rest of the way to Buffalo. The crew remained behind to fly out the next day.

A question for the passengers: What's the more frightening way to travel through a sleet storm — by plane or by automobile? Perhaps the crew of the airplane had the best idea. |

Nunda (NY) News, November 24

Emergency Field Done Just in Time

The emergency landing field of American Airways at the Ridge, halfway between Nunda and Mount Morris, was the scene of considerable activity last Friday evening when the New York City-to-Buffalo passenger plane, which passes over Nunda around 6 o’clock, landed at the field which has been completed only a short time.

Trying to guide the big plane through a sleet storm proved a hazardous undertaking for the two pilots, who radioed the Buffalo port they were landing at the Ridge.

Undaunted by the weather, the Buffalo office quickly sent automobiles to the landing field to pick up the plane’s passengers, and when the plane landed, 14 passengers were transferred to the waiting automobiles to continue their trip to Buffalo.

Modern navigation, in the advanced scientific stage of today, refuses to admit defeat even in the face of serious obstacles, as was proved to American Airways passengers on the New York City-to-Buffalo route, who appreciated the foresight of the company in providing the landing field at the Ridge where the huge plane soared down out of the sky in a raging sleet storm, with passengers and crew unharmed and none the worse for their nerve-wracking experience.

The big plane was piloted by Ralph Dodson and Pilot Underwood, who, with the stewardess, were brought to the Mary Jemison Inn, Nunda for the night by Carl Mann of the Nunda Garage, the three returning to Ridge field early Saturday morning, taking the airplane to Buffalo. |

|

|

|

| |

In November five French airlines — Air Union, Farman Lines, CIDNA, Air Orient and Aeropoatalehave — merged into a single company: Air France.

A month later United Air Lines began a new passenger and mail route between Chicago and Philadelphia, with stops in Toledo and Cleveland.

And in one of those events of interest mostly to readers of the Guinness Book of Records or guys who make silly bets at bars, Russell Holderman, manager of the airport in Leroy, New York, set out on September 18 to set a new world record for consecutive loops in a glider. He didn't just break the record, he shattered it into little pieces. That previous record was 17 loops; Holderman looped the loop 35 consecutive times in his glider before an official of the National Aeronautical Association |

|

| |

| Unfortunately, there were many other stories of plane crashes during the year, but the next one had a happy ending. It also was similar, on a much smaller scale, to the amazing story of US Airways Flight 1549, which, on January 15, 2009, was forced to ditch in the Hudson River with no loss of life, turning the pilot, Capt. Chester B. "Sully" Sullenberger, into a household name. In the 1933 incident, the pilot shared the spotlight with the hostess, who guided the passengers to safety. |

Buffalo Courier Express, November 30

Hostess Is Heroine After Crash

WINDSOR, Ontario (AP) — Nine passengers and a crew of three sat on top of the wings of a large airplane which crashed at Lake St. Clair last night until rescuers broke their way through ice and brought them safely ashore.

An American Airways plane piloted by Dean Smith of Summit, New Jersey, was forced down by engine trouble and a landing was made on the thin sheet of ice covering the lake, near Peche Island, close to the Canadian shore.

The body of the plane crashed through the ice, but the wings prevented it from going to the bottom in some 30 feet of water.

Miss Kathleen Smith of Chicago, hostess of the plane, calmly opened the door of the cabin and assisted the nine passengers to climb to a place of comparative safety atop the wings. Miss Kathleen Smith of Chicago, hostess of the plane, calmly opened the door of the cabin and assisted the nine passengers to climb to a place of comparative safety atop the wings.

By the time all were out, she was standing in ice-cold water up to her neck, but her passengers were safe. Then she climbed up beside them.

While the stranded party waited for rescuers to reach them, a vacuum bottle filled with hot soup came floating to the surface from the cabin of the plane and was salvaged. The soup was portioned out among them.

Smith, the pilot, said he had bucked a heavy headwind all the way from Buffalo and his gasoline was running low. Engine troubles added to his difficulties and he sought a landing place as he felt unwilling to risk the few added miles to Riverside, across the lower end of the lake.

The passengers, none of them injured, praised Smith for the careful way in which he “pancaked” his machine in landing in the dark on the surface of the ice. They also praised the hostess, who had been with the company only six weeks.

Ice delayed the rescuers after they hastened to the scene from Riverside. It was necessary to break a channel to the stranded plane and for about twenty minutes passengers and crew watched the battle with the ice until boats reached the side of the plane.

Thoroughly chilled and most of them drenched, all twelve were rushed to a cottage near Riverside and given medical attention. |

|

|

|

| |

| The craziest flight of the year may have been the one experienced by pilot Lee Schoenhair. This is how an Associated Press reporter described it: |

Washington Post, June 4, 1933

Flier Saves Self as Test Plane Goes Wild

OAKLAND, Calif., June 3 (AP) — A fight for life with an experimental airplane which refused to fly in a straight line, but made a series of great curves in its first test was won here today by Lee Schoenhair, veteran Oakland pilot.

The craft, redesigned from a plane wrecked in the national air races last year, struck a bump as it was taxiing along at about 70 miles an hour in the take-off. It leaped 50 feet in the air, and Schoenhair had his hands full of trouble. The plane made a big curve, getting about 300 fee above the ground.

Schoenhair attempted to land and the plane twisted downward in another curve, getting dangerously close to the ground. For six minutes the pilot struggled, at one time breaking out of the closed cockpit with the idea of bailing out. He abandoned that plan, however, when he found himself over a densely populated section of Alameda. From there the pilot swooped about until he got the plane over San Francisco Bay and it almost went into the water.

The pilot finally managed to maneuver the plane back to the airport and landed at a speed of about 120 miles an hour. He was uninjured and the plane was not damaged. An examination showed something had gone wrong with the tail control.

The plane has a wing spread of only 17 feet and a length of 19 feet, but carries a 275-horsepower inverted motor. Schoenhair said he was not daunted by his antics and would take it up again next week. Fliers said his maneuvering was an extraordinary feat.

Schoenhair flew the first Antarctic pictures of the Byrd expedition from Balboa, Canal Zone, to New York in April, 1930, for the Associated Press. In 1928 he attempted a transcontinental speed flight with the plane Yankee Doodle and also figured in an unsuccessful endurance flight that year. |

|

Schoenhair, who would go on to set some early aviation speed records, had an even more spectacular mishap in 1928 while four Ford airplanes were on their way from Detroit to Florida.

They landed for refueling in Nashville, but when the planes were set to leave, Schoenhair, in the lead plane, lost control during take-off and crashed into two of the other Ford planes. Luckily, no one was injured, and the three planes were repaired. |

|

|

| |

| HOME • CONTACT |

| |

|