| HOME |

|

An offer I couldn't refuse Early in my senior year of high school I happened upon a Sport magazine article about major league baseball player Bob Nieman, a graduate of the Kent State University journalism school. Long story short, I convinced my parents that attending a state university in Ohio would be no more expensive than the tuition charged by Syracuse University. In return I would be expected to work during my summer vacations at the highest-paying job available, which in those days usually involved construction. My father was mayor of Solvay and could pull strings to insure a good summer job for his son, though the one I worked for three months after graduating from high school paid less than construction. It was at the New York State Fairgrounds where my cousin, Tom Smolinski, and I spent the summer of 1955 doing our bit to ready the place for the annual fair held from late August thru Labor Day. Among our duties: — Walking around and around the one-mile dirt track, picking up pebbles. The highlight of the fair in those days was a 100-mile automobile race featuring Indianapolis 500-style cars. Our bosses wanted the track as pebble-free as possible. — Cleaning the horse stables, the first time that had been done in several years, which made it a most unpleasant job. I can't recall if there was harness racing that year, but for sure a few years later it did return to the Fairgrounds which had what was considered a fast track; several trotting and pacing speed records were set there. Naturally, I believe that was because my cousin and I picked up so many of those annoying, speed-destroying pebbles. — Finally, during Fair Week my cousin Tom and I got to work at the Coliseum during shows given by Bob Hope and a very young Johnny Cash. The New York State Fair is held within walking distance of Solvay, which was home to a chemical company, Solvay Process (later Allied Chemical). The village was notorious for its soot and for polluting Onondaga Lake. So when Bob Hope dragged out an old joke, he did it at Solvay's expense, the joke that goes "First prize was a week's vacation in Solvay, second prize was two-week's vacation in Solvay." A YEAR LATER I had a job with a crew that was constructing what became Interstate 690 along the west shore of Onondaga Lake. It was on that job that I had my nearest-death experience – a group of us were under a bridge being built and one of the huge beams somehow got loose and fell, missing us by inches. But most of the summer I stood on Hiawatha Boulevard directing traffic around the construction site, a dull job that was uneventful until my last week when some joker ignored my signal, lost control of his automobile and collided with some equipment. Luckily, no one was hurt. But this story is about the summer after my sophomore year at Kent State. I found a job on my own. My parents knew I was applying, but expected I wouldn't be hired, a classic case of wishful thinking ... because it was a reporting job at the now defunct Syracuse Herald-Journal. What my parents dreaded about my career choice was realized. My pay: $40 a week. This was about $60 a week less than my parents figured I'd have to contribute to my college fund for my junior year. They tried to talk me out of the job, but I resisted, saying it would qualify as the newspaper internship required to graduate. A few weeks into the summer my father learned of an unusual job opening that might be filled by someone he recommended. He liked to take advantage of such political plums because it wasn't often in Central New York that such jobs went to Democrats. The bonus: it was an night job that wouldn't interfere with my work at the Herald-Journal. Counting reimbursements plus wages, I'd make $150, which meant that by the time I went off to Kent State I'd have made almost as much as I would have working a construction job all summer. And what was this wonderful night job? Working as a state auditor at Vernon Downs, a harness track in Vernon, NY, about 40 miles from Solvay. Despite my interest in journalism, math was my strongest subject, and this particular job – which required people to calculate and verify payoffs on betting pools – was right up my alley. So I made arrangements to drive to Utica for an interview. I was told there was one other candidate, a recommendation of a Democratic politician in Utica.

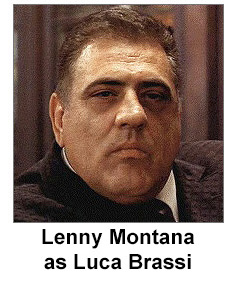

From my first night I discovered the horses weren't the only ones racing at Vernon. The state auditors and the track auditors treated tabulating as a competitive sport. As I recall, the state team usually won. The state rotated the auditors in charge. There was one chief auditor for every New York State track. Each would spend a week at one track, then switch to a different one the next week. One of these auditors was 45, which I remember only because he bet his age on the daily double every night – horse number 4 in the first race, number 5 in the second, regardless of their record or the odds. I can't possibly be remembering this correctly, but I think his name was Burt Schulman and that he was the brother of Max Schulman, the humorist and author ("The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis," "Barefoot Boy With Cheek," "Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys"). In any event, this auditor hit the 4-5 daily double three times during one of his weeks at Vernon Downs, though one of them was at Saratoga which he had attended in the afternoon. I managed to avoid placing a bet until late in my last week on the job. Each night we were free to watch a race. Finally I bet on one, having noticed a horse that seemed to tower over the rest of the field. What's weird is that I'm sure the horse's name was Buckaroo. What is it that allows people to recall so vividly things that so unimportant? Ever cautious, I bet two dollars on Buckaroo to show. I might have picked him to win if his name were Buckaroo Hanover, since all the good trotters at the time seemed to be Something Hanover. BUCKAROO may have been huge, but his long legs didn't do him much good. He finished fifth. However, I caught a break. If you're familiar with harness racing, you know lots of things can go wrong, which is what happened in this race. Two horses were disqualified and Buckaroo was awarded third place. When I drove home that night I was about three dollars and twenty cents richer. Which made for a much happier story than one told by another auditor who, weeks before my arrival at Vernon, had bet on a horse that would lead the field – until it was struck by lightning and killed. Thanks to my time at Vernon Downs I accumulated enough college money to satisfy my parents, though they never endorsed my chosen field of study. You'll never get rich as a journalist, they said. And they were correct, of course, though things eventually worked out a lot better than any one of us could have imagined. But it sure took time. Four years after graduation I still wasn't making as much per week as I did during the summer of 1956 at Vernon Downs. And I wouldn't have had that job if it weren't for Luca Brassi. |

| HOME • CONTACT |

MY INTERVIEW was short, the interviewer apologetic. He had looked at my resume and admitted I was qualified. But I was only 19 and the state law said a person had to be 21 to hold such a job. As I left his office I noticed a man in the waiting room. Years later I would recall this man when I saw his lookalike in "The Godfather." He was a dead ringer for Luca Brassi. He must have talked like him, too, because an hour later, when I arrived home, the phone was ringing. It was the man who interviewed me. "To heck with the state law," he said. "Can you start work tomorrow?" I could ... and I did.

MY INTERVIEW was short, the interviewer apologetic. He had looked at my resume and admitted I was qualified. But I was only 19 and the state law said a person had to be 21 to hold such a job. As I left his office I noticed a man in the waiting room. Years later I would recall this man when I saw his lookalike in "The Godfather." He was a dead ringer for Luca Brassi. He must have talked like him, too, because an hour later, when I arrived home, the phone was ringing. It was the man who interviewed me. "To heck with the state law," he said. "Can you start work tomorrow?" I could ... and I did.