| HOME |

|

His wife of a year, Paige Morris McGrew, said afterward she thought her husband was just clowning around and would set the firework on the ground."I didn't realize he had already lit it." Seconds later the firework exploded and McGrew was dead. IT HAS BEEN many years since I attended an authorized fireworks display by people qualified to do such a thing, but since I moved to an otherwise quiet gated community in Bluffton, South Carolina, 21 years ago, I haven't had to leave my house on July 4. I've been both amazed and appalled by the fireworks displays provided by nearby residents. A few years ago, some of them staged one of the best fireworks displays I've ever seen, though it was dangerous and no doubt illegal. I'm not sure where it originated, but the rockets that were bursting in air that evening could be seen well above the tops of at least four rows of houses between my front porch, where I stood, and the nearest field with open space enough for such fireworks. So it must be easy to legally buy professional grade fireworks, though there must be restrictions on how to use them. But each year people are killed doing just that. This year —2024 — there was a muted response to July 4 in our neighborhood; few fireworks were heard, none was spotted. Not so at Allen Ray McGrew's home in Summerville, a small city a few miles northwest of Charleston. McGrew's death was the result of an incredibly foolish mistake witnessed by his family. Way back in my childhood, I was witness to a similar mistake, but one that left a family with some minor property damage and a neighborhood with what soon became an amusing anecdote. IT HAPPENED in Solvay, New York, where I grew up on Russet Lane, a one-block street that rose gradually from its starting intersection and dead-ended at several concrete poles atop a small hill that overlooked a village park occasionally used for carnivals (or what we called "field days"). Looking north from the end of Russet Lane, you'd see a larger hill that stood between our street and Solvay's main drag, Milton Avenue, where several factories were located, including the huge complex that gave our village its name, the Solvay Process Company, so called because it produced soda ash using a process created by Belgian chemist Ernest Solvay. Anyway, that larger hill, then owned by the Solvay Process Company, was used for fireworks displays that highlighted every carnival. This no longer is the case because the area is now the site of Solvay Senior Apartments. Allied Chemical, which owned the Solvay Process Company, deserted the village many years ago. BACK IN the 1940s and '50s, Russet Lane was a social center for many kids, mostly boys, because there were four driveways where you could usually find pick-up basketball games or a touch football game (almost always traffic-free because ours was a dead end street). During the summer, we played street games in the evening, most often our version of Kick the Can, which we called Tin Can Copper. The fireworks-related event that recently came to mind probably occurred on August 16 in 1947 or '48. St. Cecilia's Church would have held its annual Feast of the Assumption carnival during the three previous days. This event was incredibly popular throughout the Syracuse area, drawing thousands for midway rides, games, food and, most importantly, a terrific fireworks show at the end of each evening, with the biggest and best reserved for the final night, August 15. So this one year, on the day after the carnival, some Russet Lane boys went to the nearby hill and rummaged around the site of the fireworks. They found a rocket that had been overlooked the night before. They took it to what was then the last house on the north side of the street. One of the boys lived there. He was older than the others, but on this day was no wiser. In his backyard was a brick barbecue, not uncommon in the days before charcoal and propane grills became popular. It had a cooking surface about three feet by three feet, and the structure included a small chimney that rose another two feet at the end of the cooking surface. The boys placed the rocket at the base of the chimney, thinking four or five feet of chimney would guide the rocket straight up. But the firework wasn't lit until every kid on the street had been alerted, which is how I came to be one of the spectators. IMAGINE a prequel to "Happy Days," a story set in the 1940s when Richie Cunningham and friends were in elementary school. Call it "Russet Lane." I am Richie, but the show's star is Frankie Bagozzi. He is The Fonz, but he's not played by Henry Winkler, but by a young Steve McQueen, who always reminded me of Frankie. So there we were, a bunch of kids standing by the barbecue at what we judged to be a safe distance, waiting for our own fireworks display in the middle of the day. Seconds passed, but nothing happened. Frankie decided to investigate. He looked into the chimney, but withdrew his head just in time. FRANKIE BAGOZZI was one of Russet Lane's most unforgettable characters, an undersized, but pugnacious instigator, the prime suspect in all mischief. In part, you could blame Frank Sr., recalled as a shadowy figure who all but disappeared from his son's life early on. For years I thought Frank Bagozzi Sr. was a big-time gangster, Syracuse's answer to Al Capone. It wasn't true, not even close ... though Frank Sr. was arrested a few times on gambling charges. The last time I saw him was after one of those arrests. I was 19 and working as a part-time reporter for the Syracuse Herald-Journal, temporarily covering the police beat. Frank Sr. had just made bail when he spotted me at the station. It had been several years since I'd seen him; I was surprised he remembered me, even more surprised that he knew why I was there. "Jack," he said, with melodramatic sincerity, "I was framed!" An answer for everything. Like father, like son. FOR OUR after-dark street games, Frankie's favorite hiding place was a maple tree not far from the telephone pole that served as the starting point of each game of Tin Can Copper. The person who was "it" had to spot the other players. Once spotted, that player was captured and had to come out of hiding and stand close to the pole in an area that served as our jail. If "it" wandered far enough from the pole, Frankie would come down from the tree, dash to the pole and free the "prisoners." Frankie always climbed to the highest branch that would support him. He wasn't the only neighborhood kid to hide in that tree, but he was the smallest of the climbers – and the only one who could completely disappear among the leaves. (Among Frankie's next door neighbors were the Mathews brothers, Daniel Jr. and James. Daniel, better known to us as "Red" for his flame-colored hair, became an attorney, like his father, while James became a well-known Syracuse-area priest. They, too, were known to use the tree, and one night the owner of the property on which the tree was located, came home while a game of Tin Can Copper was in progress. He knew someone was high up in his tree, but he had the wrong suspect. "I know you're up there, Red Mathews! Come down immediately!" As I recall, Frankie waited him out. On anoher night Frankie did slip and fall, breaking an arm. As soon as his arm mended, Frankie was back in the tree, as high up as ever.) FRANKIE COULD BE surprisingly creative. Soon after my father was elected mayor of Solvay, he brought home a village-owned tape recorder, a primitive and bulky reel-to-reel machine that came with no options beyond on, off, rewind and fast forward. I showed it to Frankie who suggested we tape our own radio show, a spoof of "Dragnet". He was the producer, director, writer, star and special effects department. We followed that with "The Shadow"; the sound Frankie squeezed out of a tiny squeak in our sunroom door was truly frightening. THE QUINTESSENTIAL Frankie Bagozzi story: It's 1944, Frankie's eight years old, I'm six. Among my favorite toys is a set of tin soldiers. One day I can't find them, and that's the first bit of news my mother reports when my father comes home from work. His response: "Frankie!" My father charges up the street and as he approaches the Bagozzi house, he spots the soldiers spread out among the front yard shrubs. When Frankie comes to the door, my father accuses him of stealing the soldiers. "I didn't steal them," said Frankie matter-of-factly, "I took 'em on maneuvers." My father breaks up. He'd never been able to stay mad at the irrepressible kid he liked more than any other. Besides, he realized Frankie was telling the truth. "Okay," says my father, finally fixing a straight face, "but when maneuvers are over, bring the soldiers back." "Yes, sir!" barks Frankie, giving my father an exaggerated salute. Maneuvers ended the next day and the soldiers returned to Fort Major. I MOVED to Ohio soon after I finished college and ran into Frankie only a couple of times during visits to my parents, who remained in their house on Russet Lane. Frankie was in business for himself, first with Bagozzi's Smoke Shop. Later he opened the first video store in the Syracuse area, Bagozzi's Video. The last time I saw him was at his small restaurant in Westvale Plaza. At a high school reunion several years ago, some of us began exchanging Frankie Bagozzi stories, but couldn't top the classmate who told us that as a result of her daughter's recent marriage, she was now Frankie Bagozzi's mother-in-law. It wasn't long after the reunion that Frankie learned he had lung cancer. He died on New Year's Eve, 1990. He was 54. Frankie was an Air Force veteran who served nine years on active duty, most of that time in Japan. Later he was a 20-year member of the 174th Tactical Fighter Wing of the Air National Guard – a unit known as The Boys From Syracuse. He was survived by his wife, Patricia, and daughter Danielle, who was 4 when Frankie died. To paraphrase a couple of lines made famous by "Naked City," there are one hundred reasons I'm grateful I grew up on Russet Lane. Frankie Bagozzi is one of them. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| HOME • CONTACT | ||

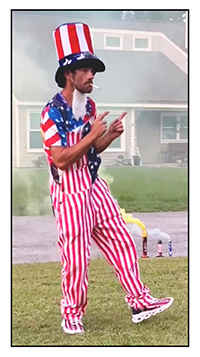

When I read about the July 4 death of a South Carolina man who lit a firework and put it on top of his red, white and blue Uncle Sam hat, I had a flashback to a near-miss experienced some 75 years ago by my best childhood friend after some boys in our neighborhood found a rocket that somehow hadn't been fired in a fireworks display the night before.

When I read about the July 4 death of a South Carolina man who lit a firework and put it on top of his red, white and blue Uncle Sam hat, I had a flashback to a near-miss experienced some 75 years ago by my best childhood friend after some boys in our neighborhood found a rocket that somehow hadn't been fired in a fireworks display the night before.

Undoubtedly drinking was involved in the South Carolina incident. Allen Ray McGrew (left), a 41-year-old HVAC worker, was celebrating not only July 4, but his son's recent engagement.

Undoubtedly drinking was involved in the South Carolina incident. Allen Ray McGrew (left), a 41-year-old HVAC worker, was celebrating not only July 4, but his son's recent engagement.