| HOME |

|

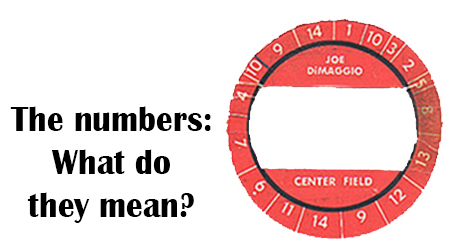

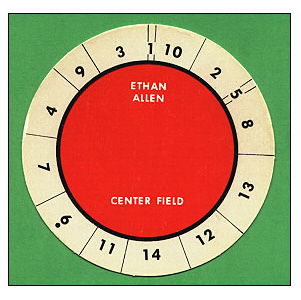

Allen (above) still holds the University of Cincinnati record for the highest batting average (.475). He later earned a master’s degree from Columbia University. After retiring as a player, Allen was the National League’s director of motion pictures. He also wrote several instructional books about baseball. He became the Yale University baseball coach in 1946, retiring in 1968. His teams played for the NCAA baseball championship twice, losing to Southern California in 1947 and California in 1948. His 1948 Yale captain was a first baseman named George H. Bush. Allen’s Yale teams won more than 300 games, earning him a place in the College Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame. Allen also was pictured on the Wheaties cereal box in 1946. That may have involved a promotional gimmick connected with what many of us remember most about this remarkable fellow – his board game. ALL-STAR BASEBALL was introduced in 1941 by Cadaco, then a fledgling Chicago company known as Cadaco-Ellis. The game was instrumental in establishing Cadaco one of the giants in the toy and game industry, though it took a few years before the company honored the creator by changing the game’s name to Ethan Allen All-Star Baseball. All-Star Baseball is considered one of the 50 most important board games of all-time, but its appeal was limited. Cadaco stopped making it in 1993, though ten years later the company marketed what it calls a classic version. I don't believe it's available anymore; I couldn't find it listed when I recently checked Cadaco's website, www.cadaco.com. Allen always claimed he created his game for boys aged 9 to 12, boys who were avid baseball fans. He was both amused and frustrated when All-Star Baseball developed a cult following among those who played the game as boys in the 1940s and ‘50s, then continued to play it as adults in the 1960s and beyond. Allen considered these people odd. I know, because he told me so – several times. More on that later. If you played a season’s worth of games, each player’s statistics would approximate those he had generated on the field. The focal point on most discs was the space alloted for category number 1 – the home run. Everybody loves a slugger, and those who played Allen’s first game probably chose Joe DiMaggio for their team earlier than, say, Roy Cullenbine, because DiMaggio clearly would deliver more home runs. The #1 on the DiMaggio disc took up much more space than Cullenbine’s. THE FIRST All-Star Game manufactured by Cadaco-Ellis featured 40 discs based on statistics from the 1941 season. That’s why Cullenbine was included. He played for several teams during his 10-year major league career and his lifetime average was a lackluster .276, but in 1941, playing for the St. Louis Browns, Cullenbine hit .317, with 98 runs batted in with only 9 home runs. Cullenbine may be best remembered for his ability to draw bases on balls. He walked 121 times in 1941 which gave him a higher on-base percentage than DiMaggio (.452 to .436). Of course, 1941 was the year of Joe DiMaggio’s famous 56-game hitting streak. Allen couldn’t duplicate the hitting streak, but he did create a disc that would have DiMaggio hitting about 30 home runs for every 600-or-so flicks of the spinner, while maintaining a batting average well above .300. Allen saw the game being played by boys who could assume the roles of major league managers, each selecting a team of all-stars. He said he didn’t expect anyone, particularly an adult, to create leagues, play full seasons and keep statistics. Pitching skill played no part in the outcome, but Ethan Allen All-Star Baseball produced scores that seemed real. No two games were alike. DiMaggio might go 20 games or more without the spinner landing on the 1. Or he might hit two home runs in one game, or one home run in three consecutive games. All-Star Baseball was an immediate success, but Allen and Cadaco never stopped tinkering with it. Allen believed he should have limited the discs to eight categories, requiring a second spin on a separate disc to determine what happened, for example, on a ground ball to the shortstop, or a single to center field with a runner on second base. There were many baseball plays unaccounted for in the original game, but that fact seemed to bother Allen more than it did those who played the game. He kept coming up with ways to make his game more realistic, more strategic. The company eventually introduced eight-category discs, but there was a storm of protest. The game’s biggest fans had been adding discs to their collections each year. They had no use for eight-category discs. They preferred the simplicity and speed of the original game. Like me, others who played the board game probably didn’t love or appreciate baseball quite the way Allen did. Statistics were more important to us than strategy. And like me, other All-Star Baseball fanatics had their own ideas on how to expand the game’s limits without requiring extra spins, which would have added to the playing time. One idea, apparently common among the game’s aficionados (or kooks, as Allen called them), involved the space marked by the number 11 (a double). The simple version of the game said runners advanced two bases on a double. But when I played, a runner on first would score if the point of the spinner landed between the digits. I met others who did the same thing. Likewise, I had a way of determining a fielder’s choice – the runner on first base was out at second, the batter safe at first – that didn’t involve a second spin. And I used dice to determine the fielder whose error allowed a hitter to reach base. (For more on my misspent youth, see A Game for One.) (People create unique rules for every game, it seems. As I moved from job to job, state to state, I was surprised at how many Monopoly players separately – but almost simultaneously – created a lottery from money paid for fines and street repairs, with that money going to the next person to land on Free Parking.) IN 1979 Sports Illustrated published an article about Ethan Allen All-Star Baseball, mentioning its cult-like following. The article prompted me to write SI a letter, telling how much I enjoyed the game. I also mentioned the memorable (some might say infamous) disc that turned Aaron Robinson, a pedestrian catcher, into a superstar. Robinson's first disc was based on impressive 1946 statistics (he only played 100 games that season) and subsequent editions of the game featured an Aaron Robinson disc that remained pretty much the same, despite the catcher's lackluster hitting performances thereafter. SI published my letter, someone at Cadaco read it and forwarded it to Allen, who, at 75, was living in retirement in Chapel Hill, NC. Allen wrote to me, I wrote back, and we became pen pals during the summer of ’79. I saved Allen’s letters which describe efforts to improve his game and various disputes with Cadaco about his suggestions. Allen and I often disagreed about the game, especially about his desire to make it more complicated. Re-reading his letters today makes me wish I had saved copies of the letters I sent him because his end of the correspondence leaves the impression he was trying to calm a raving maniac. I couldn't have been that bad. One of his letters began, “Holy mother, I’m glad there are only a few of you kooks. You’re trying to make an adult game out of a kids game. I told that (All-Star Baseball) crowd at the first convention in Chicago I didn’t care how they played the game – only that they bought it.” Despite his denials, Ethan Allen did care about his game and those who played it. He cared a great deal, and he'd go on, paragraph after paragraph, explaining the need for special discs that would deal with situations that developed on such things as a pitch out, passed ball or a fly ball mishandled by an outfielder with the bases loaded. With one of his letters he enclosed three discs from an advanced version of his game, Strategic All-Star Baseball. One of those discs was for Jackie Robinson.

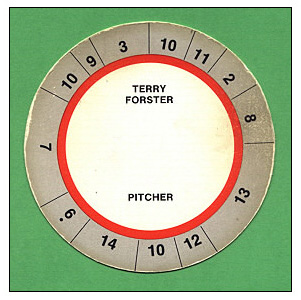

“Am I ever obsessed with Strategic (All-Star Baseball),” he wrote. “You bet I am, and if I can get my format published with supplementary rules, it will run other advanced games off the market. I would be willing to bet on that – unless a computer-type game can be reasonably realistic.” It was a bet he couldn’t win. Strategic All-Star Baseball never caught on. ALL-STAR BASEBALL was only one of his creations. Allen said he had 13 games copyrighted, “but I cannot get into a game company to demonstrate them.” His games involved football, basketball and track, as well as baseball. I found it interesting that even Strategic All-Star Baseball, one of the most detailed sports games I’d ever seen, failed to account for pitching and fielding skills, something that earned much more respect for APBA Baseball, which is played with dice and elaborate charts. “I do not feel qualified to classify pitchers,” Allen wrote to me, “and I would not do so even though there might be scientific evidence for same. This is also true of fielding ability. My reason is mainly a relationship with players which I do not want impinged. Perhaps I have told you the story about Zeke Bonura, former White Sox first baseman. He was always high in the fielding records. In a game against the Indians a ball went by him into right field. Later Jimmy Dykes, manager of the Sox, asked Luke Sewell, who had been coaching first base, if Bonura should have fielded the ball. ‘No,’ Sewell replied, ‘but anyone else could.’ ” ANOTHER ASPECT ignored in Allen's game was a player's base-stealing ability. There were two base-stealing discs, but the results on both applied equally to all runners. I mentioned that in one of my letters, saying if I so chose, I could have Boog Powell steal 50 bases a season. (In real life, the 6-foot-3, 230-pound first baseman had just 20 stolen bases in 17 seasons.) Allen's reply: "If you would do that with Powell, I wouldn't trust you. You are not playing the game according to the player's ability." So Allen's game depended on an element of trust, though I suspect many who played it took advantage of the base-stealing loopholes. All-Star Baseball was based on statistics, and statistics say that runners have a better chance of stealing third than stealing second. Something good was almost bound to happen if you tried to steal third in Allen's game. Even young players also recognized something else about Allen's game. Since it's assumed there is no designated hitter rule with All-Star Baseball, you select, as your pitcher, the one who is the best hitter available. Given a choice between Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax (a poor hitter) and Schoolboy Rowe (a pitcher who hit .300 or better three times), you went with Rowe every time. And I'm sure kids whose game included a set of old-timers were bright enough to use Babe Ruth as their pitcher. After all, Ruth was one of the best left-handers in the American League for a few seasons. Because Forster spent most of his career as a relief pitcher, he had only 78 at bats in 16 seasons. It was from those 78 at bats that Forster's disc was created. Forster had 31 hits, which gave him a lifetime batting average of Allen did send me a copy of a 1979 Chapel Hill newspaper article. He told writer Ken Roberts “I never have played a game (of All-Star Baseball), not a complete one, anyway.” Yet he claimed it was possible to develop a spin that would land in approximately the same spot on the disc every time. That was an indication Allen was telling the truth about his actual experience playing his game. Even with years of practice, there was no way to control the spinner. FOR ALLEN to use the names of all-stars past and present in his game, he had to get a release form signed by the players, who received nothing in return. Allen contacted each one himself and got cooperation most of the time. One exception was New York Yankee relief pitcher Sparky Lyle. Allen told the Chapel Hill writer that he made several attempts to reach Lyle, but heard nothing until the pitcher finally sent this message: “Don’t send me any more of this garbage.” Allen had no trouble getting permission from pitcher Jim Perry, but Perry’s more famous brother, Gaylord, refused to sign a release. Roy Smalley III, who played in the American League from 1975 to 1987, was apologetic for waiting so long to sign his release form. When he finally did, he told Allen that he had grown up on the game. He said his father, Roy Smalley Jr., a Chicago Cubs infielder in the 1940s and ’50s, used to play it. Allen didn’t deal with the Major League Players Association, but his advancing age and a changing business climate brought the players union into the picture when Cadaco took full control of the game. The union's cooperation is obvious in the 1993 edition of All-Star Baseball and the classic version that came out in 2003. Allen and I exchanged letters for about two months, then he concluded, “It seems ridiculous to keep this correspondence going when we are so much at odds. However, I will, of course, acknowledge any further correspondence and make any comments I deem necessary.” He added, “By the way, when do you find time to work, or is your wife the breadwinner?” EVENTUALLY Ethan Allen All-Star Baseball included a disc for the player who created the game. By then Cadaco was doing something that – to me, at least – defied logic. The discs still used numbers 1-14, but several were redundant as Cadaco attempted to impose Allen's eight-category system.

The more significant numbers were (1) home run; (5) triple; (7) and 13) single; (9) base on balls; (10) strike out; (11) double. Despite the change, it didn't take much ingenuity for "kooks" like me to interpret each spin in a way that a second one was never necessary for any batter. For more on how I got involved with Ethan-Allen All-Star Baseball, plus a look at the game's original format and rules, see A Game for One. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HOME • CONTACT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

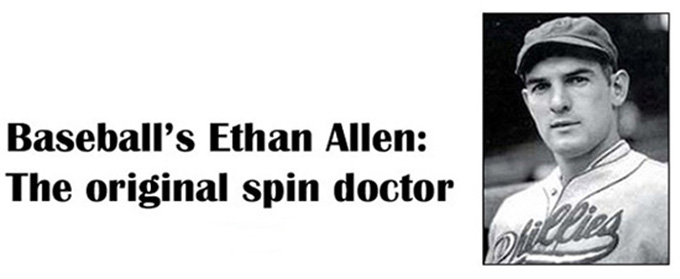

Ethan Nathan Allen (1904-1993) was not your average major league baseball player. He went from the campus of the University of Cincinnati to the hometown Cincinnati Reds in 1926 and remained in the majors for 13 seasons, also playing for the New York Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns. He retired with a .300 lifetime batting average, having his best season in 1934 when he hit .330 and tied future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler with 42 doubles, tops in the National League that season.

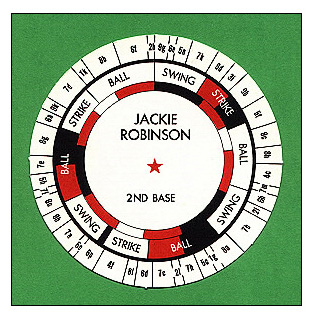

Ethan Nathan Allen (1904-1993) was not your average major league baseball player. He went from the campus of the University of Cincinnati to the hometown Cincinnati Reds in 1926 and remained in the majors for 13 seasons, also playing for the New York Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns. He retired with a .300 lifetime batting average, having his best season in 1934 when he hit .330 and tied future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler with 42 doubles, tops in the National League that season. There are 40 spaces in what he termed the “outer circle”, which meant there were many more lines for the spinner to straddle. There was a middle circle that told you if the pitch was a ball or strike, and whether the hitter swung. A wild pitch, passed ball, balk and a hit batsman were accounted for. There was even an inner circle for pitch-outs. His letter mentioned an electrified spinner. I got dizzy just looking at the disc, but Allen really believed in this version of his game:

There are 40 spaces in what he termed the “outer circle”, which meant there were many more lines for the spinner to straddle. There was a middle circle that told you if the pitch was a ball or strike, and whether the hitter swung. A wild pitch, passed ball, balk and a hit batsman were accounted for. There was even an inner circle for pitch-outs. His letter mentioned an electrified spinner. I got dizzy just looking at the disc, but Allen really believed in this version of his game: .397, higher than Ty Cobb. Any time the spinner landed on (7) or (13), Forster had himself a single; the (11) is a double. You can bet that when it came to All-Star Baseball, Forster was a starting pitcher who also did a lot of pinch hitting.

.397, higher than Ty Cobb. Any time the spinner landed on (7) or (13), Forster had himself a single; the (11) is a double. You can bet that when it came to All-Star Baseball, Forster was a starting pitcher who also did a lot of pinch hitting. Numbers 2, 6 and 12 were all ground balls requiring a second spin over a lettered pie chart affixed to the spinner. Likewise, numbers 3, 4, 8 and 14 were all fly balls, also calling for a second spin (which produced more outfield errors than you'd see in a local Little League).

Numbers 2, 6 and 12 were all ground balls requiring a second spin over a lettered pie chart affixed to the spinner. Likewise, numbers 3, 4, 8 and 14 were all fly balls, also calling for a second spin (which produced more outfield errors than you'd see in a local Little League).