| HOME |

|

|

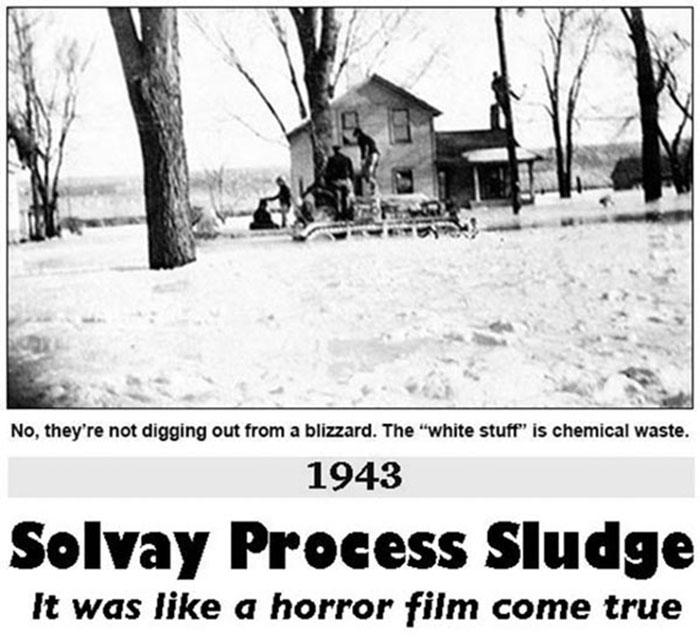

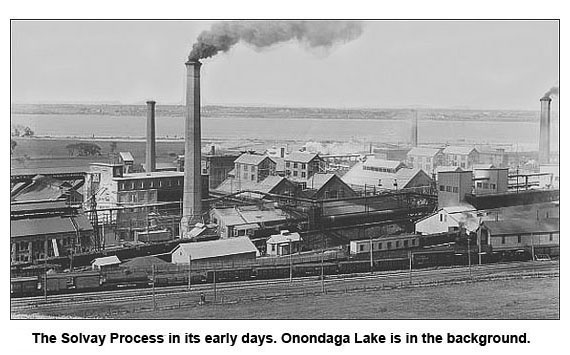

My New York hometown was named after a Belgium chemist, Ernest Solvay. His process for producing soda ash was used by some enterprising Americans to found — with Ernest Solvay's approval — the Solvay Process Company, the cornerstone of the village where I grew up in the 1940s. Having the Solvay Process Company a short distance from our street was both good news and bad. The factory employed thousands of people, including my father, my grandmother and an uncle who lived next door. The company also provided many services for village residents and in the early years was Solvay's social, medical and educational center. However, the factory also belched smoke and filled the air with a gritty soot that undoubtedly was hazardous to our health. Waste from the Solvay Process Company, along with sewage from the nearby city of Syracuse, destroyed once-lovely Onondaga Lake. Polluting the lake forever tarnished the reputation of the Solvay Process Company, which in the 1920s became a division of Allied Chemical. Because it was considered so important to the economic life of the area, the Solvay Process Company had its way on several controversial environmental issues, which is why, despite strong opposition, the factory dumped its waste along the west shore of Onondaga Lake. The company built huge holding areas that were surrounded by tall, concrete dikes. These were the most visible waste depositories, though at least one of the smaller plants operated by Solvay Process openly flowed its waste directly into the lake. In the early 1940s there were eight large waste beds across the street of the New York State Fairgrounds on State Fair Boulevard, with a ninth waste bed under construction. Those who had opposed the dumping at the turn of the century predicted it was just a matter of time before at least one of the dikes containing the waste would burst. Most of those concerned, obviously, were residents of a section of the Town of Geddes known as Lakeland. Company officials insisted this would not happen, though they admitted that only the waste exposed to air would harden. Everything under the crusty top would remain quicksand soft. [At the bottom of this page is story that should have served as a warning.] At 3 a.m. on Thanksgiving Day, 1943, a dike broke. For people unlucky enough to be living in the few houses along this strip of State Fair Boulevard, they were about to experience the terror of a real-life blob. And this was 15 years before the Hollywood version. The United Press reported it like this: |

|

|

|

Fortunately, there were no fatalities, which seems incredible in view of this description of the incident: |

|

|

|

Later the Herald-Journal reported that while Solvay Process executive and engineers were unable as yet to pinpoint the cause of the break in the dike, they were satisfied it wasn't caused by sabotage. An estimate 40,000 tons of sludge had poured across State Fair Boulevard. A company spokesman said the soupy Solvay waste “consists of a slurry of flocculated material including calcium carbonate, magnesia, and small quantities of calcium chloride and salt brine, and is non poisonous.” That spokesman said the waste takes years to harden, but everything underneath the hardened shell would remain soft, though not liquid. The dike that broke was just four years old. The flood of waste covered 85 acres inside the Fairgrounds, more across the street. It was said at the time that even if those who were forced to leave their homes wanted to return — which was unlikely — they probably wouldn't be able to because of the permanent damage inflicted on the area by the sludge. Eleven people remained at the Stair Fair Hotel. They had no power, but were getting heat from a wood-burning stove. By the end of Friday — less than 48 hours after the break — more than 2,500,000 gallons of water had been pumped into the area to flush the sludge into drainage sewers, which, I am certain, took the sludge either directly into Onondaga Lake or into Nine Mile Creek, which flowed into the lake, which was doomed many years earlier. On Saturday Syracuse's leading newspaper, which at the time was the now-defunct Herald-Journal, published an editorial about the incident in which the writer tried hard to present a balanced view: |

|

|

|

|

|

South of the Fairgrounds on State Fair Boulevard, near the Willis Avenue intersection, the Solvay Process Company had a waste canal that was unaffected by the accident. This man-made canal was 1,500 feet long, eight feet wide and up to 14 feet deep. Each day 85,000,000 gallons of waste was pumped from the Solvay plant into the canal, which emptied into Onondaga Lake. It was pumped through pipes and created a fast current. According to a story in the Herald-Journal, a wooden fence ran along part of one side, presumably the side away from the company, as a way of preventing bystanders to get too close to the canal. Unfortunately, there were places where it was all too easy for anyone to approach the canal. And in September, 1944, there was tragedy when some young boys from a neighborhood nearby were playing in the area. One of them, seven-year-old Angelo Greco, walked too close to the edge and slipped into the canal. The current carried the boy downstream, into the lake. Three days later his body was found where the current had taken him — to the other side of the lake. The canal may have replaced pipes that carried the waste into the lake many years earlier. One of those pipes broke in 1901, creating a mess on Willis Avenue, but at that time the company was able to stop the flow at the source and the problem was quickly fixed. Well, one problem, maybe. A bigger problem was what the waste was doing to Onondaga Lake. It's unlikely that problem can ever be solved. What seems incredible is that there weren't more tragedies like the one that took the life of young Angelo Greco. It was all to easy for the public to gain access to areas that were dangerous. Fortunately, these areas were so barren and hideously ugly that they almost shouted, "Stay away!" However, in September, 1940, a fire in one of the waste beds attracted curious spectators, including a teenager unfamiliar with the area — and its dangers. This teenager survived, but only because there were Solvay firemen nearby, firemen who risked their lives to rescue him: |

|

|

|

After World War 2 the Solvay Process Company dumped its waste elsewhere on company-owned land out of sight from most area residents. In 1985 the factory was officially closed and demolished soon thereafter. However, the waste that polluted Onondaga Lake remains very much an issue because efforts are being made to dredge the lake and redeposit the waste on land once owned by the Solvay Process Company in the Town of Camillus where residents have complained of the awful odor this has created. Years earlier some 30-foot high wastebeds along State Fair Boulevard somehow hardened enough to be turned into parking lots for the annual New York State Fair. Other wastebeds were topped with soil that allowed for the planting of grass and shrubs. A section of Interstate 690, which connects with the New York State Thruway, runs along the west side of Onondaga Lake. Those unfamiliar with the history of the area might well think they've been transported to the surface of the moon. If only they knew how much uglier it looked 60 years earlier ... Only locals with long memories can envision what now seems something out of a childhood nightmare or a bad horror movie. Such was the scene along State Fair Boulevard on that Thanksgiving Day when many Lakeland residents found little to be thankful for. |

|

|

|

| Once upon a time ... | |

|

|

|

|

| For more about Onondaga Lake: | |

| http://onondagacountyparks.com/onondaga-lake-park/ | |

| http://www.npr.org/2012/07/31/157413747/americas-most-polluted-lake-finally-comes-clean | |

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onondaga_Lake | |

| For more on Solvay way back when, check out the Solvay-Geddes Historical Society |

|

| HOME | CONTACT |