| HOME |

|

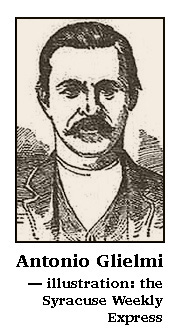

I found them during a detour from an unusual story about an incident occurred just outside of Syracuse in the village of Solvay, my hometown. The Glielmis were related to one of the men who played a role in helping several Italian immigrants who were having a difficult time adjusting to life in the United States. There were many reasons for this; chief among them was a language barrier that several Italians seemed slow to overcome. Antonio Glielmi, who headed the family, was born in 1844 in Campagna, Provincia di Salerno, Campania, Italy, and his last name was actually Guglielmo. Most immigrants who found themselves subjects of His colorful wife was born Lucrezia Cappuccini, also in Campagna, Italy, though her page on geni.com erroneously lists her birthplace as Syracuse. When she began making news, her name appeared several ways in newspapers, particularly after she re-married in the early 1890s. Both Lucrezia and Antonio Glielmi were ambitious, and considering the several unfortunate events that disrupted their lives, each managed to accomplish a lot along the way. He sold peanuts and fruit from a portable stand that was set up facing what is now Clinton Square, at the intersection of West Genesee and Salina Streets in downtown Syracuse. The Post-Standard building stands where there used to be a hotel called Empire House. Glielmi worked so hard and was so thrifty that by 1890, not far from Clinton Square on North Franklin Street, he had managed to erect a three-story building that became an Italian boarding house run by Lucrezia while her husband sold peanuts and fruit. They had had six children, one of whom, Arthur, died in infancy. Their youngest, Anna, was born in 1889. After that, Lucrezia Glielmi came into her own, and for good reason. Antonio Glielmi wanted to have the only peanut and fruit stand on what then was called Market Square. He offered to buy out the competition, and thought he had succeeded with a man named Gotto, who accepted $100 and promised he would no longer sell peanuts in the square. However, Gotto didn't exactly keep his promise. He encouraged his brother, John, to take his place in the square. John agreed, but turned the actual peddling over to a man named Niccolo Devita (whose name would appear in various spellings after the tragic incident of April 7, 1891). That incident was the fatal shooting of Devita by Antonio Glielmi, who claimed his life had been threatened by Devita. The two men frequently argued over the locations of their peanut and fruit stands. Area farmers who sold their fruits and vegetables had first priority, with the peanut vendors pushed to the fringes. However, the farmers closed their stands and left the area early each afternoon. That's when Glielmi and Devita would race to set up shop in what they considered a better location. That's also when things became nasty between the two men, who became bitter enemies, though there is a hint in some stories published after Devita's death that he had been encouraged, perhaps by the Gotto brothers, to taunt Glielmi. Why? Maybe to prompt him to make an offer the Gotto's couldn't refuse — like $2,000 or so to shut down the competing stand. Unfortunately, according to newspaper stories, Devita's remarks often were insults about Mrs. Glielmi, who had acquired an unsavory reputation as a woman who was having sexual relations with other men. There were more than 30 men staying at the Glielmi boarding house, and Devita was saying Glielmi wasn't really the father of some of his children. Newspapers soon claimed this was the reason Glielmi shot Devita, but Glielmi denied it, and I think he was telling the truth. Glielmi had been a model citizen until April 7, 1891. Yes, he could be hot-headed, especially after having a few drinks. But unlike many Italian immigrants, he had never pulled a knife or a gun on anyone, and had never made any threats. He would claim he shot Devita because he was in fear for his life, saying Devita had announced his intention to kill him before that day was over. Witnesses said the two men argued a few times that day. Things got particularly heated after their last race for position when another vendor moved his stand. Glielmi won the race, and Devita responded by trying to tip over his rival's peanut roaster. It wasn't long after that — about 9 p.m. — when Glielmi pulled out a long-barreled .44 caliber revolver and shot Devita in the head. When Devita's body hit the sidewalk, Glielmi stood over him and fired three more shots. Those last three shots were witnessed by two Syracuse policemen, James Hogan and Thomas Leahy, who wrestled Glielmi to the ground, seized his revolver and arrested him. Glielmi claimed he had acted in self-defense, that Devita has threatened to kill him with a knife he was known to carry with him at all times. However, when police checked the crime scene, they found no knife on Devita, or his peanut and fruit stand, or anywhere in the area. Devita may have been bluffing the whole time, but his continuous taunting and threats had gone too far. Two months later, Antonio Glielmi was found guilty of second degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment at the state facility in nearby Auburn. But for Antonio and Lucrezia Glielmi, things were just getting interesting. Coincidentally, two days after Antonio Glielmi shot Niccolo Devita, there was another killing in downtown Syracuse, resulting in a trial also heard by Judge George N. Kennedy. The defendant in that trial was Moses Fleetwood "Fleet" Walker, a catcher who had played for the Syracuse Stars of the International League in 1888 and 1889. Walker is recalled today as one of the few coloreds — as he was identified at the time — to play major league baseball before Jackie Robinson. In his trial, Walker was found not guilty by reason of self-defense, and the jury's verdict was greeted with applause. It wasn't clear whether people supported Walker because of the facts of the case or whether it was because he was a popular baseball player. Lucrezia Glielmi was injected into the case by newspapers, though their reasons were rather vague. Typical was this paragraph the day after the shooting in a story published by the Auburn (NY) Bulletin, which might have had a Syracuse correspondent:

I found no story about her appearing before Judge Thomas Mulholland, longtime Syracuse police justice. After the trial, she reportedly tried to raise money to mount an appeal, but apparently failed. I can find no stories about her during the next three years, but she obviously was busy, because by 1895 the Syracuse newspapers were saying she had divorced Glielmi and married a much younger man. This second husband is a bit of a mystery man. For one thing, there was no agreement on the man's last name, though the first name, when given, was always Vincenzo. As for a last name, it was variously reported as Latorio, Delore, Doloir and D'Aloi. I lean toward D'Aloi, but only because members of the Aloi family became prominent in the Syracuse area many years later. In a legal decision handed down in 1911 — which we will get to later — he is identified as Vincenzo Doloir. Whether Lucrezia ever actually divorced Glielmi remains uncertain, as was the legality of her second marriage. This second husband may, in fact have been a live-in companion. In any event, he seems to disappear in 1895, which was a busy, busy year for Lucrezia, who emerged as a wheeler dealer who put fear in the hearts of long-time downtown Syracuse residents. Here I feel the need to inject a guess into the situation. That guess is the when her husband was sent to prison, Lucrezia Glielmi received a legal opinion that influenced her movements after she was convinced there was no chance of appealing or overturning the verdict in Antonio Glielmi's murder trial. Over the next several years, that legal opinion would be proven correct by rulings in at least three cases, but each time it was reported by the Syracuse newspapers as though the ruling were a big surprise. That ruling? In New York, a person who received a life sentence was legally dead. That raised the question of whether Lucrezia Glielmi went to the trouble of divorcing Antonio before"marrying" Vincenzo Doloir — or whatever his name was. Or whether a divorce was actually needed. There also was some question of whether she had actually married the man she was living with after her first husband went to prison. But in 1895, she sued Doloir for divorce, claiming non-support. She also sold the boarding house on North Franklin Street, making what newspapers called a tidy profit. Glielmi got word of the deal, and from prison contacted his attorney to initiate a lawsuit that would enable him to get his share of the money his ex-wife received for the property. In a strange little twist, Lucrezia, in her own mind, had voided her second marriage and had retaken Glielmi's name. What follows is how, on July 17, 1895, the Syracuse Herald explained the lawsuit's outcome: |

|

|

|

I believe that last paragraph is misleading. I'm sure the woman had been advised much earlier about the law's position on a man sentenced to life imprisonment. However, the big news on July 17, 1895 was reported earlier in that Syracuse Herald story, and it was news that seemed to have the potential to change the futures of Antonio and Lucrezia Glielmi. |

|

|

|

Ceylon H. Lewis, the former district attorney, was Glielmi's defense lawyer. It's interesting that Judge George N. Kennedy joined in the effort to commute Glielmi's sentence, which indicates the judge issued that sentence only because the law demanded it. Governor Morton, incidentally, was a former vice president of the United States. What Glielmi should have considered at this point was a legal action that would bring him back to life. Perhaps he and even his attorney thought such a move was unnecessary, since, obviously, Antonio Glielmi was very much alive. Or was he? Meanwhile, Lucrezia Glielmi was on a roll. She was well aware that most people who lived just outside what was considered the Italian section of Syracuse were fearful of having Italians move into their neighborhood. Some of these folks were willing to pay to prevent this from happening. |

|

|

|

The Syracuse Herald had published a similar story and put it under the headline: "ITALIAN ENCROACHMENT." Later in the year, the woman took legal steps to insure that she had severed all ties with her second husband, though, as was most everything in her life, the question of this marriage was never legally settled, something that would be mentioned in a future court battle. Things were so confused about this second husband that within a short time he was so far out of her life that no one seemed to know if the man were alive or dead. For awhile, any newspaper stories about Lucrezia Glielmi seemed to assumed that Doloir or D'Aloi had died. In 1898, generally known as Lucrezia Glielmi again, she was back in the news, this time for running a boarding house on West Beldon Avenue, near her old place on North Franklin. (Many years later, this section of West Beldon Avenue was torn up to make was for Interstate 690). On May 26, some of her boarders were involved in a brawl; one man was shot and killed, two others were stabbed and seriously injured. Mrs. Glielmi wasn't home at the time; she was attending a circus several blocks away. However, that didn't prevent the Syracuse Journal and the Syracuse Courier from claiming the woman was responsible. |

|

|

|

|

|

There was nothing in the story to support the headlines, and the Courier even managed to introduce another spelling for the last name of the man Lucrezia Glielmi may or may not have married a few years earlier. Both stories claimed the brawl at her boarding house began over an argument about which boarder the landlady liked best; later stories, including those about the trial of the two men — Tomasso Pirro and Fidello Spinello — accused of killing Letitio Demides — said the fight broke out during a card game or a game of dice, and a side rule involving "the king of the beer" who determined which players were entitled to a drink. However, Mrs. Glielmi's reputation was such that the newspapers got away with blaming her for the incident, just as they continued to say she was the reason Antonio Glielmi shot Niccolo Devita, though all the trial testimony said the murder was the result of a peanut vendor turf war. (A similar murder in New Orleans in 1891 was blamed on the Mafia, which caused speculation that the Devita killing had been ordered by the Syracuse Mafia, but Antonio Glielmi was simply mad as hell and couldn't take Devita anymore. A Mafia murderer probably wouldn't pump three unnecessary bullets into his victim.) Unlike Donald Trump, who's always talking about fake news, Lucrezia Glielmi had reason to complain about how the press treated her. The woman may have had her faults — well, we all do, right? — but she was subjected to frequent comments about her appearance and accused of things that were never spelled out. And most of the time her name was misspelled. And if another family member did something that attracted attention, Lucrezia got dragged into that, too, though her name might be slightly altered, as it was in the following story: |

|

|

|

Notice the unnecessary comments about the teenager's looks. Her husband would later be identified as Carmon Sedaro. Julia's name actually was Virginia. They returned and moved into her mother's boarding house. Months later, on November 5, 1900, the Glielmi family made news again when Antonio was released from Auburn State Prison. He had served nine years and five months on what originally had been a life sentence. Ah, the benefits of good behavior. But if he were expecting a reconciliation with his wife, Glielmi was in for disappointment. According to a story in the Syracuse Herald, Mrs. Glielmi refused to take him back. However, he did return to selling peanuts and fruit from a stand in downtown Syracuse. In 1903, Virginia Glielmi Sedaro eloped again — the Syracuse Journal, so fond of her mother's name, identified her as Lucrezia Virgilia (cq) Glielmi. Her husband complained to police that his wife had stolen money and run off with a man identified at Frank Pazzo. The Syracuse Herald identified her as Delia Glielmi and said the man she had fled with was Frank Lazarro. In any event, they were wanted on a charge of grand larceny. Lucrezia Glielmi responded by having her son-in-law arrested, charging him with defrauding her out of a board bill in the amount of $17. Finally, newspapers settled on the man's correct name — Carmelo Sidari, who, after settling matters with his mother-in-law, tracked down his wife in Rochester, where he confronted Lazzero, who later told police Sidari fired a gunshot at him. Sidari was arrested, but when the truth of the matter came out, the charge was dropped, and he was released. He returned to Syracuse and it appears from other records that he and his wife reconciled, settled down and had five children. Sidari went on to run a restaurant on Syracuse's North Side, which became predominately Italian. Things went quiet for the Glielmi family in 1905, and remained that way until an odd incident in 1908 briefly put the 1891 murder back in the news: |

|

|

|

Three Syracuse newspapers — the Herald, the Journal and the Post-Standard — had fun with this story. The ending of the above story indicates the Herald was skeptical, while the Journal seemed to believe the skull definitely belonged to Devita, while the Post-Standard said the skull causing all the fuss had actually been found in the swamp six years earlier, and that the holes in the sides of it were not made by bullets. Devita's skull probably disappeared forever after being tossed in the trash, but it was interesting that his skull had been on exhibit for many years in the district attorney's office. The Tamarack Swamp mentioned in the story exists no more. It was on the east side of Syracuse, and was filled in and developed not long after this story appeared. And if you're confused by the mention of a Mrs. Gunness in the second paragraph, well, that's a reference to Belle Gunness, whose death in 1908 in LaPorte, Indiana, led to the discovery of several bodies. She is now regarded as one of the country's first serial killer. In 1909, Lucrezia Glielmi erected a three-story brick building at 325 Fulton Street, and was residing there when she died on October 14, 1910. (I believe Fulton Street no longer exists.) Her death triggered two interesting events. First, Antonio Glielmi decided to remarry, and in May, 1911, wed Miss Fina Santello. He also filed suit to gain a share of Lucrezia Glielmi's estate, estimated to be worth $20,000, a huge amount in those days. Included in the estate were five parcels of land on the North Side, plus a contract to purchase six lots elsewhere in Syracuse. Also wanting their shares were the Glielmi children — Joseph, Virginia, Louise, Anna and Constance (who was married to James Lanzetta). The case went before Judge William S Andrews, who echoed an old ruling when he declared that Antonio Glielmi was still dead. The judge also said that when Lucrezia Glielmi died, she was still married to Vincenzo Doloir, who, the judge declared, was still alive. That must have been news to everyone. If Doloir, D'Aloi or whatever his name was hadn't died, why didn't he come forward and declare a share of his late wife's estate? Antonio Glielmi simply shrugged off the ruling, though it must have galled him that he received nothing from a real estate empire built on the foundation he had laid. Nevertheless, Antonio Glielmi must have found some humor in being granted a marriage license while technically dead. Despite the lawsuit over his first wife's estate, Glielmi apparently got along well with his children, and in 1918, after his second wife died, he moved in with his son. A year later, the legally dead Glielmi married for a third time, to Martina Barbieri. He was 76 years old, she was 80. However,, in 1920, after just a year of marriage, his health failed, and he and his wife went to live in the Onondaga County Home, where he died in November, finally putting an end to the Glielmi saga, freeing his children and their children from being reminded in the press, each time their family name appeared in print, of that terrible day in 1891. |

|

When it comes to Darwin's theory of evolution, I've always had my doubts. — I mean, what self-respecting ape would admit to being related to a creature that wastes his precious thumbs on Twittering (or even twiddling). And what would the ape say about prostitution, pornography, gambling or hunting and fishing just for the sport of it? ("Eat our catch? Hell, no, we let taxidermists stuff 'em so we can mount 'em on a wall!") However,, I have a great deal of respect and admiration for the relatively rapid kind of evolution accomplished by immigrants — such as Antonio and Lucrezia Glielmi — who arrived in the United States unwanted, and were confined to a ghetto in a land of weird customs, sometimes contradictory laws, and an often illogical language ("I before E except after C"). It took most immigrants only one generation — no more than two — to be completely assimilated into the culture and make great contributions, something a lot of today's Americans seem to have forgotten. |

|

| HOME | CONTACT |

newspaper stories couldn't read English; if they did, they probably would have discovered a reporter had unknowingly changed their names. Antonio was initially identified as Gleimi, but soon that was changed to Glielmi, which I assume is pronounced Glee-ELL-me, or (don't ask me why) YOLL-me.

newspaper stories couldn't read English; if they did, they probably would have discovered a reporter had unknowingly changed their names. Antonio was initially identified as Gleimi, but soon that was changed to Glielmi, which I assume is pronounced Glee-ELL-me, or (don't ask me why) YOLL-me.