HOME

The period from 1915 to 1930 was marked by several explosions connected with the Solvay Process Company and its Semet-Solvay division. There were other incidents — unfortunately, explosions and fires were all-too-frequent at chemical plants in the early 1900s — but spotlighted here are the most spectacular from this 16-year period.

1915: It blew off the roof:

Chemical companies and explosive accidents go together. The Solvay Process Company, later a division of Allied Chemical and Dye, had its share of explosions. There was one in 1915 that foreshadowed the disastrous 1918 explosion at the Split Rock plant when more than 50 workmen were killed.Fortunately, the following explosion did not take any lives, but it was a reason residents of Solvay and vicinity never completely relaxed. Any loud noise might mean disaster.

Syracuse Post-Standard, April 1, 1915

Eighteen men were injured, two seriously, in a gas explosion last night around 6 o’clock at the newly reconstructed carbolic acid plant of the Semet-Solvay Company.The force of the explosion blew the entire roof from the building, crumbled portions of the walls to powder and shook houses and buildings in Solvay and Syracuse.

Startled residents immediately called police officials and newspaper offices to find out the extent of life lost and damage done, and thousands of persons poured into Solvay to visit the scene of what they believed would be a frightful disaster.

Within ten minutes Dr. R. W. Chaffee and Dr. W. P. Kanar had established a temporary hospital at the Solvay Process police station and every ambulance in Syracuse had been summoned. The work of rescuing men from the building was accomplished rapidly and before 6:30 p.m. every one of the injured had been removed to the station.

Eight men, less seriously injured than the others, were sent to St. Joseph Hospital in the hospital ambulance and police patrol. Eight were taken to the Hospital of the Good Shepherd, and two others to Crouse-Irving Hospital.

So quickly was first aid applied that at 7:30 p.m. the temporary hospital was cleared of patients and the large crowd which had assembled around the Solvay offices had dispersed. As rapidly as possible relatives of the men who had been at work in the buildings were notified of the condition of the injured. In most cases they were allowed to visit the patients after their removal to hospitals.

Dr. R. W. Chaffee, physician for the Solvay companies, examined all the victims. He said he found none of them in critical condition. “Barring unlooked for complications, all the men will come through nicely,” said Dr. Chaffee

To the light construction of the building is attributed the fact there was no loss of life. The plant is built of steel, with four-inch walls of brick, which easily gave way before the explosive force.

Officials of the Semet-Solvay Company were unanimous last night in attributing the cause of the explosion to gas which had in all probability escaped through leaks in retorts or containers. They declared that no explosives are used or manufactured in the plant, and that as far as could be ascertained, upon a hasty examination of the place, the sole cause of trouble lay in the formation of an explosive gas of which the workmen were unaware.

Whether smoking or sparks ignited the gas or whether it was purely a case of spontaneous combustion, they were unable to state. The carbolic plant was recently reconstructed and manufacture of this acid resumed after a lapse of several years. Machinery used in the process is new and, it was admitted, not completely tested out by time.

Probably twenty-five men were at work in the building when the explosion occurred. Of this number, six or seven were uninjured and went to their homes immediately. Of the eighteen who received hospital treatment, but two, Charles Crippen and Patrick O’Neil, were in a serious condition late last night. There is a chance both may recover, although they are badly burned and bruised.

The day shift had left the building and the night shift had been working since 4 p.m. In addition to these employees, several repairmen were working overtime in different parts of the structure.

Inside the building — which is 65 feet wide, 200 feet long and three stories high — the men were distributed in groups of five or six on different floors.

The detonation brought hundreds of Solvay residents, wives of employees and fellow workmen of the injured to the plant.

In the city, the general belief at first was that an earthquake had taken place. The tremendous force of the explosion can be understood when it is known the shock was felt at Skaneateles, about twenty miles away.

The Syracuse Post-Standard (April 1) reported Joseph Volinsky, 22, of 305 Lakeview Avenue, who was working on the second floor of the building, was blown through a window by the force of the concussion. He was working on the second floor of the building when the explosion occurred.

Remarkably, his injuries were not serious, though he was taken to Crouse-Irving Hospital for treatment. X-rays showed no broken bones.

Volinsky said he was hurled several feet through the interior of the building and out of a window. He landed on railroad track, and when he tried to walk awa, the pain was too severe, so he lay down and waited for help to arrive.

According to the Syracuse Jounal (May 1), an investigation of the explosion revealed the cause was carelessness by a Semet-Solvay Company employee who left uncovered a vat of benzol. Fumes escaped and became ignited by nearby fire pots.

In June there was a work-related death at the benzol plant. Charles Martin, 29, of 118 Caroline Avenue, was killed while making air pressure readings in a tank. Valentine Cole, 25, of 213 Woods Road, risked his life in an effort to rescue Martin. Cole sank into unconsciousness, but was revived by two physicians called to the scene.

Martin had the dangerous duty to take air pressure readings in tanks about 20 feet deep. Fumes in the tank made it risky for anyone to remain down for more than a minute. Cole saw Martin unconscious in the bottom of the tank, and hurried down a ladder. and tied a rope around Martin, but he was dead by the time he was pulled up. Cole managed to climb the rope, but collapsed after he reached the top.

Martin was survived by his widow, Irene; his parents, Mr. and Mrs. William Martin, and one brother, Frederick Martin.

In July there was another explosion at Semet-Solvay. Luckily there were few injuries, none of them serious, but the property damage was more extensive than from the incident earlier in the year. However, the plant that was destroyed turned out to be obsolete and therefore expendable. Sparks from a passing locomotive were the cause of the explosion, igniting benzol from an overlowing tank.

There was yet another explosion at a Semet-Solvay plant, this one in December, but the resulting fire was small and easily contained.

Circumstances were another indication of how dangerous working conditions were during this period, especially when chemicals were involved.

1916: Preview in Split Rock

On February 18, fivce men were killed and five seriously injured when a tank exploded in the Semet-Solvay benzol recovery plant in Split Rock.The dead were Lyman Green, 300 Cogswell Avenue, Solvay; Harry Danser, Skaneateles, and three Syracuse residents,William J. Guckert, Max Lepedus, and William Curran.

The injured were John Masters of Marcellus, and four Syracusans, John McKeever, Daniel Fitzgerald, George Griswold and John W. Osbeck.

According to the Syracuse Post-Standard (February 19), Martin H. Knapp, assistant to the president of the Solvay Process Company, who gave out the first statement, said the explosion was caused by too much pressure applied to one of the tanks in the building.

1918: The Big One

The July 3, 1918 explosion and fire at the Semet-Solvay plant in Split Rock took the lives of at least 50 men, several of them workmen killed by the blast, but most of them workers and company police and security people who died while attempting to put out the fire, or at least prevent it from spreading to a building where a large quantity of TNT was stored.Semet-Solvay was one of several plants throughout the country making TNT for military purposes during the first World War. The TNT made at Split Rock was for depth charges (bombs) being used by the Navy against German submarines.

The death toll at Split Rock varies from source to source. Fifty is the usual number given, but lists of the men killed indicate the actual toll might have been slightly higher. Some early estimates claimed as many as 70 or more may have perished.

Cause of disaster was not determined, though Onondaga County Coroner Ellis Crane, who conducted an inquest, censured the Semet-Solvay Company for not maintaining a guard in the granulator room where a fire broke out, triggering the explosion. Crane also noted the lack of a sprinkler system which might have snuffed the fire and prevented the explosion.

However, on the day of the explosion the water pressure at the plant was so low that a sprinkler system might not have done any good. There were a series of explosions and then a horrific fire. Company hoses proved useless in fighting the fire, forcing workers to use buckets. Some buildings were deliberately destroyed in a successful effort to keep the fire from spreading to a building known as "Dry Canada" where TNT was stored.

Company officials intended to resume operations as quickly as possible, but five weeks after the accident the United States government relieved the Semet-Solvay Company of the manufacture of TNT. Instead the plant would be rebuilt for the manufacture of other products for the war effort. Chief among those would be picric and nitric acids.

Before the fire and explosion the Split Rock plant was producing 30,000 pounds of TNT a day, which represented a small percentage of the amount being produced in the United States for the war, which finally was drawing to a close.

Syracuse Journal, August 7, 1918

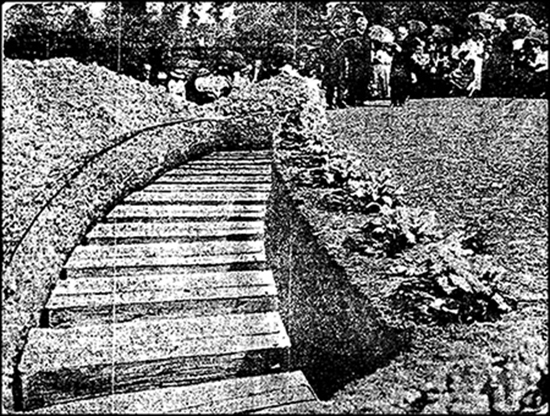

Fifteen unnamed but honored dead of the Split Rock explosion of July 2 were buried side by side in a semi-circular grave at Morningside Cemetery this morning. It was the last echo of the explosion which snuffed out fifty lives and injured as many more.The funeral cortège, largest ever seen in the city, headed by fifteen hearses and followed by forty carriages and automobiles, was solemnity in itself. No demonstration accompanied the cortège as it slowly wound its way to cemetery, but the hundreds who viewed the procession doffed their hats in honor the men ho gave their lives that the boys over there should be amply supplied with death-dealing explosives.

At the graveside, a rabbi, a priest and a preacher paid tribute to the unidentified in the ritual of the respective religions.

Fully a hundred relatives of the men listed as missing since the explosion and presumed to be among the charred forms which have lain in the county morgue for more than a month unrecognized, gathered in the receiving rooms of the little Montgomery Street block shortly after nine o’clock.

Shortly after ten o’clock the procession was on its way, wending slowly through streets lined with hundreds who paid their small might of honor and respect to the dead as the cortège passed by.

A semi-circular gravesite, probably forty feet in length, had been prepared. Eighteen members of the Solvay Police Department acted as pall bearers, six to each coffin as it was brought from the hearse and lowered in the waiting rough box in the grave.

Though many officials of the Solvay companies were present, none of them participated in the services other than as spectators.

Coroner S. Ellis Crane announced this morning he had issued death certificates for all the missing, for both the unidentified and the missing lists are the same. Each body had been named, and the following names will be inscribed on the granite memorial to be erected over the plot by the Semet-Solvay Company:

Glenn Charles Bates, 1349 West Onondaga Street; Herman George Baxter, 108 Tanglewood Avenue; John W. Brown, 118 Barnes Avenue, Floyd Eastman,, 409 Hartson Avenue; Charles Finnerlin, 108 Temple Street.

James Jones, 201 Caroline Avenue, Solvay; Francis J. Keefe, 445 Cannon Street; James King, Skaneateles; Clarence Mundy, 224 Stuart Avenue; Eugene Rice, Split Rock.

David Rush, 1012 Montgomery Street; Theodore Silverstein, 625 Harrison Street, George Sitterly, Lyons; John Westman, 819 East Genesee Street; George F. Wood, 412 Abell Avenue, Solvay.

1929: Terrifying reminder

The May 10, 1929 explosion of chlorine gas at a Solvay Process facility at the northeast edge of the village was the company's worst since the horrific 1918 explosion at the Semet-Solvay plant in Split Rock. One life was lost during the 1929 explosion. Those injured recovered, though the lives of some, I'm sure, were forever changed.James Carlisle, 30, of 131 Hudson Street, a workman, died in Syracuse Memorial Hospital as a result of having inhaled a large quantity of the gas.

According to he Syracuse Journal (May 10), one other worker, Charles Nye of 307 Herkimer Street, went to the Hospital of the Good Shepherd in a serious condition. Thirteen others were overcome and treated at a first aid station by Dr. R. W. Chaffee, Solvay plan physician.

Solvay officials I. V. Maurer, manager of operations, and his assistant, G. A. Milligan, announced that they had been unable to determine the cause. Both officials sought to minimize the danger from the accident and said that the financial loss would be nominal.

Carlisle was found unconscious in the yard in front of the plant by rescuers, who donned gas masks to make a hurried trip through the plant property in search of workmen. Carlisle apparently fell while fleeing with a score of others from the immediate vicinity of the damaged tank.

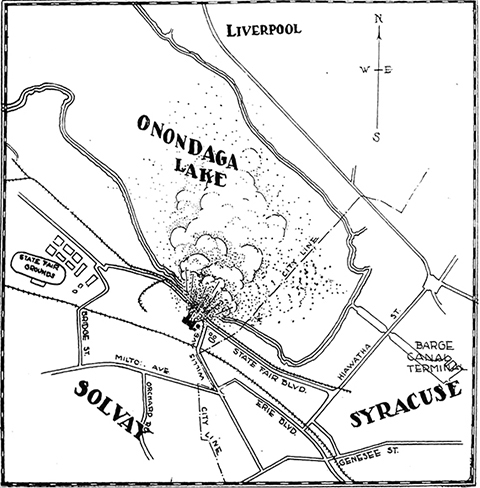

Soonn after the 3 a.m. explosion, the odor of the gas was detected in Liverpool, carried there by the wind. And for more than an hour after the blast and the thousands of cubic feet of the deadly gas was released, the gas hung like a green pall over the surrounding territory.

Workmen at the chlorine plant fled immediately after they heard the blast. Experienced employees knew the deadly nature of the chlorine, but although all of them were in the open a few seconds afterward, more than a score were felled as they ran for their lives. Most of them were able to get out of the plant yard before collapsing.

The gas is similar to the deadly gas used in the World War. Had the wind been blowing from the northwest, the entire village of Solvay would have been in grave danger.

Above: A Syracuse Journal map showing the location of the explosion and how clouds of gas moved over Onondaga Lake toward Liverpool.

1930: Firemen snuff blaze

Early in the afternoon of July 3, the Solvay fire department, with a big assist from Syracuse fire fighters, successfully prevented an explosion that would have been bigger and louder than anything scheduled for the next day's holiday celebration in both communities.The problem was a fire dangerously close to tanks holding 10,000 gallons of benzine in the mono-chloro plant of the Semet-Solvay Company. Origin of the blaze was unknown, but it may have been caused by the breaking of an electric light bulb, causing a spark which set fire to liquid or gas in the plant.

I found only one story of the incident, in the Syracuse Journal (July 3), which reported only one man was slightly injured. He was an unidentified employee of the place, who jumped to safety from a second story window shortly after the fire started.

The Solvay volunteer fire department was called, but it was soon determined help was needed to prevent the flames from reaching the tanks. There also were several drums of gas stored in the area. Syracuse firemen arrived with huge tanks of Foamite, effective in fighting this type of blaze. It took an hour for firemen to get the blaze under control.

Workmen in the plant risked their lives to prevent an explosion, running through fire and smoke to shut off pipes carrying benzol into the tanks. Two of these men were overcome and were hurried to the shop hospital. First aid was applied and they quickly recovered.

When the flames were at their height, thick black clouds of smoke rolled up from the burning building and drifted over the village, causing great alarm.

As usual company executive said there was little danger of wholesale gassing of the area around the plant, and downplayed the danger of the flames causing an explosion in the chlorine gas tanks.

For more on Solvay way back when, check out

the Solvay-Geddes Historical Society

HOME CONTACT