| HOME |

|

|

|

Bixby's 1930 murder still a mystery |

|

Solvay's most compelling story of 1930 broke on April 18. It was the tragic conclusion of a three-part drama that started several months earlier: |

|

|

|

Six months later, the gasoline station was robbed again: |

|

|

|

|

|

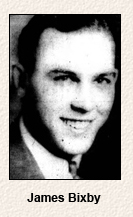

The fact the robber (or robbers) had been successful both times made one employee vow he would not allow it to happen again. Later co-workers would recall James Bixby's reaction to the second robbery: "That guy'll get away over my dead body if he ever shows up when I'm around." And at 11:45 p.m. on April 18, James Bixby was on duty, all by himself, when a taxi cab pulled into the station: |

|

|

|

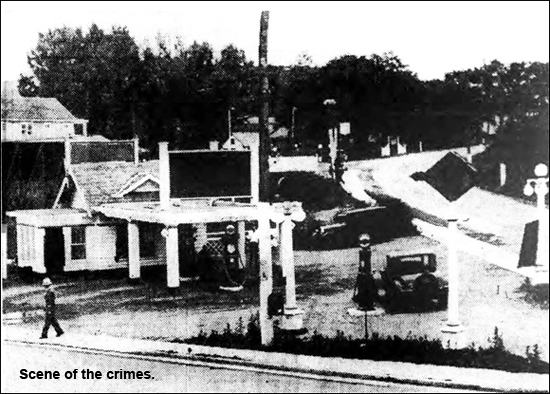

James Bixby died at 2 a.m. the next morning. It was Easter Sunday. During the next few weeks police would question several possible suspects, but the murder remained unsolved. Tragedy aside, the Bixby case took one strange turn after another, and along the way there were several moments that were darkly humorous. From the get-go the news stories lacked or gave short shrift to tiny details that may have been important. Like how did the robber arrive the first time? And the second? Either he was on foot, or he had a partner who waited in an automobile. Did the attendants notice two vehicles driving off? Also, why be puzzled about the bullet holes in the windshield of the first stolen car? The robber simply engaged in malicious mischief, shooting up an automobile for no reason. And if he abandoned the car in the middle of nowhere, that's more reason to believe he had a partner in another automobile. Missing from the story of the third robbery is information about the condition of the taxi cab after the thief fled. For example, were there bullet holes in the door, put there by Bixby's shots? If so, how many? GASOLINE STATION robberies were fairly common, especially at those which remained open until late at night or around the clock. The service station at West Genesee Street and Montrose Avenue was an ideal target, located at the edge of both Syracuse and Solvay, with four getaway routes from which to choose, two of them leading to a maze of roads in a sparsely populated area. One story identified the location as West Genesee Street and Charles Avenue, but Charles Avenue runs north from the intersection, Montrose Avenue runs south. The gasoline station was tucked in on the south side of West Genesee at Montrose Avenue. "West Genesee Street turnpike" was a term used occasionally to denote the road as the main route from Syracuse to points west, but it was not much of a highway by today's standards. One thing is for sure about the third robbery — it was a solo effort by a young man who arrived in a taxi cab he had stolen earlier than evening. Interestingly, this time he escaped on foot and quickly disappeared. |

|

WITHIN HOURS police had a suspect in custody, but taxi driver Alfred Hemming was certain this particular man did not hijack his car. Also, despite Bixby's confidence that at least one of his shots had hit the robber, police weren't looking for men who had been wounded. It appeared Bixby had hit the car and either missed his target or had, with perhaps one shot, inflicted minor damage that did not result in much bleeding or require a doctor's attention. Nowhere is there a mention that any blood — except Bixby's — was found at the scene. Also, there is only one mention — by Charles Post, after the second robbery — that the man police were looking for wore a mustache. State police, after a high-speed chase that began 30 miles away near Weedsport, soon arrested a 26-year-old man from St. Johnsville who confessed to 17 thefts. This man, however, used his own vehicle in committing his crimes, a vehicle that was wrecked when he lost control of it while attempting to flee the troopers. The vehicle was loaded with things reported stolen in LeRoy, in western New York. Also found was a .45 caliber automatic, loaded except for one bullet. While the man's recent robberies were west of Syracuse, he had been more active in the eastern half of the state, especially in Montgomery and Herkimer counties. For whatever reason, perhaps a shortage of food during the Depression, the 1920s and early '30s was a bad time for chicken farmers. This particular bandit confessed that his crimes included the theft of more than 400 chickens. Police tried to make a connection with the Solvay gasoline station robbery, and with several others recently committed in Syracuse, but it was almost immediately obvious the St. Johnsville chicken thief had nothing to do with Bixby's death. OTHER SUSPECTS were picked up and questioned in Syracuse, and released. Abruptly the search turned to Detroit where police had found a man in a car stolen in Weedsport on the day of the crime. Why police were hung up on Weedsport was never explained in any way that made sense. Yes, Weedsport is close to Auburn and Auburn is the home of a state prison, and, yes, it is possible a man released from that prison might have purchased a hat from an Auburn haberdasher before returning to his life of crime. On the other hand, that cap found at the murder scene might have belonged to the hijacked cab driver or one of his earlier fares. That Merritt Way was mentioned as the cap's possible owner defied logic. (More on Mr. Way later.) Had NCIS investigator Anthony DiNozzo offered such a theory, Leroy Jethro Gibbs would have given him at least one hard slap on the back of his head. Police continued to theorize about robbers from Auburn, a city located about 25 miles from Syracuse. Police felt Bixby's killer had served time at Auburn Prison and was acquainted with these other robbers, and that perhaps the killer was the man being held in Detroit. A week after Bixby was shot, a state police officer was dispatched to Michigan to bring back the car and the thief, who was quickly ruled out as a suspect. Meanwhile, a nickel-plated.38 caliber revolver, described as similar to that used by the killer, was found by two men about a mile from the gasoline station. The men were walking along railroad tracks when they noticed a metal object glistening in a nearby driveway. There was the potential for an unfortunate accident because the men believed the gun wasn't loaded. One of them decided to pull the trigger, luckily aiming it at the ground. You guessed it — the gun fired. The man finally checked for bullets and discovered the gun was loaded, but that two shots had been fired recently. The two men then did what they should have done immediately — they called Syracuse police, who sent the gun to a ballistics expert in Rochester for a determination if it was the weapon that killed James Bixby. That was the last mention of the gun, which leads me to believe it was not the weapon in question. AS THE CASE cooled, things began to to get weird. Don Schultz, the gasoline station attendant who was held-up in the first robbery, was on duty July 26. A car carrying three men pulled into the station and Schultz was certain one of them was the robber. No crime was attempted; almost certainly no crime was intended. The man's presence was an odd coincidence and, for him, damn inconvenient. The man with the robber's face had been hitchhiking on West Genesee Street a few miles west of Solvay when he accepted a ride from someone headed east in an automobile that was running low on fuel. Guess where the driver stopped to fill 'er up? Schultz claimed the man jumped from the car and scurried away down Charles Avenue. However, he also said the man first thanked the driver for the lift. If this man really were the robber, he apparently didn't own a car. This, I believe, could have been an important point. THE CASE became more bizarre 11 days later when Schultz and a Solvay friend, Ray Pawlick (the young man who had taken Bixby to the hospital), went swimming at Snook's Pond, southeast of Syracuse, in Manlius. There Schultz noticed two men in the parking area in a small coupe. Schultz was convinced one of the men was the robber. He and Pawlick approached and engaged the two men in conversation. Neither of the men was interested in conversation, Schultz later told the Syracuse Journal, and neither did the would-be robber show any sign that he recognized the gasoline station attendant. With good reason, it turned out. When the two men drove away, Schultz and Pawlick followed them in their car for a mile or two, noted the license number, then set out for the nearest Syracuse police station. A check of the license number revealed the car was owned by a Baldwinsville resident. It was an interesting bit of detective work, but fruitless. Police questioned the man Schultz had identified. He was Joseph Pietrafessa, a Syracuse University student, who was quickly ruled out as a suspect. Earlier Schultz had identified a man named Harold Hilton as the robber, but the Rochester resident established he was nowhere near Solvay on Good Friday. Schultz's eagerness to help police would later make him seem like an unreliable witness. TWO WEEKS later state troopers arrested a Buffalo man who confessed to some robberies. Schultz was called in to look at the man, but did not recognize him. Neither did motorcycle patrolman Ralph Margiasso, who had been shot by a speeding driver he had attempted to stop on the Syracuse South Side. (I found it odd that state police took the Buffalo man to Margiasso's bedside, either at the hospital or his home, which seems risky, especially if that suspect actually had been the shooter. Which he wasn't, fortunately.) The state of journalism in Syracuse may have reached a new low on August 14, 1930, when the Journal published an account of a Margiasso dream. In the dream, he said, he discovered his shooter and Bixby's killer were one and the same. That remains a possibility, even to this day. Unfortunately, Margiasso never caught up with him. Or them. Weeks later a 24-year-old amateur boxer named Edward M. "Irish" Ostrander was arrested near his father's home in Kansas and brought to Syracuse, charged with shooting Patrolman Margiasso and Mrs. Alvone Dunham, an innocent bystander. The arrest was made largely on the basis of the victims' identification of Ostrander as the shooter, but the jury was more convinced by the young man's plea of not guilty and his account of his movements that evening, which did involve some time in Syracuse, but apparently not any speeding along South Salina Street. Ostrander had no previous record. |

|

|

|

That's the headline that greeted Journal readers on December 11, 1931. The story, which later would grow way out of proportion and briefly impact the James Bixby case, began like this:

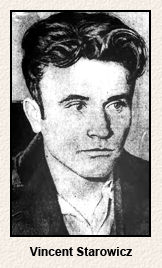

Over the next few months it became apparent Vincent Starowicz and his "leap for freedom" were not what they seemed. Starowicz may have been many things, including a bandit, but he would never be described as a leader. Starowicz had attempted his leap moments after he had identified Albert Sherwood, alias Thomas Norton, 32, of Utica, as his accomplice in a series of robberies. Starowicz was prevented from making his jump by motorcycle policeman John Forsythe, who had helped arrest the man after a robbery at an East Syracuse motel in which the owner was shot and wounded. Police soon decided the attempted leap was actually intended as a suicide attempt by Starowicz, prompted by fear when he came face to face with Sherwood. Starowicz would later implicate another man, Joseph Nedza of Auburn, briefly leading to Sherwood's release. However, all three men were soon convicted and sentenced to 40 years at Auburn prison. Three months into that sentence, Starowicz remained deeply troubled and frightened for his life. So he declared Nedza had nothing to do with the crime, that his only partner during the robbery was Sherwood. That was probably the truth — indeed, Nedza was released from prison — but by again pointing a finger at Sherwood, Starowicz reinforced his reputation as a snitch. So he did something unbelievably desperate: |

|

|

|

THIS MADE for a story that was so full of remorse it was almost heartwarming. Except it wasn't true. Folks at Auburn prison knew it immediately, but the Syracuse newspaper didn't check their story with the warden, Joseph H. Brophy. Instead the newspaper jumped the gun and misled readers with this headline: |

|

|

|

A page 2 headline credited Starowicz's lawyer as being the "CENTRAL FIGURE IN SOLVING 1930 MURDER AND HOLDUP." Beneath the headline were large photos of attorney Irving Devorsetz and shooting victim James Bixby. An article the next day in the Auburn Citizen-Advertiser revealed why Starowicz couldn't possibly have killed James Bixby. Starowicz was behind bars at the time, at Elmira Reformatory where he was spending a year for a parole violation. Police theorized the confession was a convoluted suicide attempt — pleading guilty to murder in the first degree in order to be sent to the electric chair. Warden Brophy asked that Starowicz undergo a mental examination. Joseph Nedza of Auburn, who now carried the nickname "Lucky" because of his release from prison in 1931, was arrested again in 1933 on a burglary charge. This time around police were suspicious from start, thinking he had been set up by the real culprits. In 1948 Nedza received $7,800 damages in settlement of a $50,000 action he filed for "erroneous conviction" in 1931 for which he served five months in Auburn Prison for a crime he did not commit. |

|

ATTENTION TURNED to another Joseph — Joseph Neri of Syracuse — who first made news in April, 1931, when he pleaded guilty of leaving the scene of an accident. He was sentenced to 30 days in Jamesville Penitentiary. By the time he was released he would find himself in more trouble — on two fronts. Who provided the tip, no one would say, but an investigation led police to believe the 21-year-old Neri was the man who held up several gasoline stations a year earlier. Donald Schultz and Charles Post were called in to look at the latest suspect in the robberies at the gasoline station at West Genesee Street and Montrose Avenue. Schultz and Post agreed — Neri was the man. Also adding his two cents was Merritt Way, a game warden from Newark, New York, who just happened to come upon a gasoline station holdup in Syracuse at South Salina Street and East Seneca Turnpike on the night of April 11, 1930. At the risk of making Central New York in the 1930s sound like the Wild West, Merritt Way was packing heat that night and he got into a shootout with the robbers and took a slug in a leg. This so upset Mrs. Way that she threw caution to the wind and hit the robber over the head with a flashlight before he made his getaway. (Now try to figure out why any policeman could have thought that a hat worn by Merritt Way could have found its way to a Syracuse taxi cab. The only way the robber could have gotten Way's hat was to steal it during a gunfight and hold on to it after Mrs. Way whacked him over the head.) Statements by Mr. and Mrs. Way apparently didn't carry much weight with the district attorney, who decided to charge Neri for only the first two robberies at the Solvay gasoline station. Neri was in prison when Bixby was shot, so he was not held responsible for that crime. AS IF THIS STORY couldn't get any wackier, Neri was out on bail in October. That's when he decided to marry a young Syracuse woman, Sophronia May Duquette. He'd soon learn she was keeping a secret. About the only thing Joseph Neri did right during this period was hire the Shanahan brothers, Richard and Paul, as his lawyers. (Defense attorney Paul Shanahan would become a New York State legend.) Neri's first trial on the robbery charges ended with the jurors hopelessly deadlocked. At the second trial two months later the jury wasted little time deciding the young man was not guilty. (That Neri was the third man Schultz had identified as the robber worked in favor of the accused.) However, just before that trial began, Neri was named as corespondent in a divorce suit brought by Myron J. Beach, who claimed he was married to Sophronia May Duquette. The ceremony was performed January 15, 1928 in Solvay by Justice of the Peace John D. Kelly. (Don't know why, but a lot of marriages performed in Solvay during this period later became issues in bigamy cases.) Mrs. Neri, only 21, did not appear to contest the suit, but submitted an interesting document as evidence. On October 8, 1931, three days after she married Joseph Neri, Sophronia wrote her own divorce decree and sent it to Myron Beach at 125 Hastings Place, Syracuse.

Interestingly, in the 1930 census Myron J. Beach is listed as single and living with his parents. Anyway, I found nothing more about Beach's lawsuit, but in 1936 Neri asked for an annulment from Sophronia Neri on grounds his wife was bigamist, and he cited the 1928 wedding in Solvay as the proof. Sadly, none of this advanced the James Bixby case, which remains unsolved. On August 30, 1932, the gasoline station at West Genesee Street and Montrose Avenue was robbed for the fourth time. Attendant Joseph Davidson offered no resistance in the face of a revolver, simply emptying the cash drawer of $25 and giving it to the armed man. |

|

Afterthoughts |

|

In 1930 the intersection of West Genesee Street and Montrose Avenue was at the eastern edge of a rural area. There were a few nightclubs and speakeasies down the road to the west, and nearby on Fay Road, but to lots of folks this was the sticks. That would change after World War 2 when one of Onondaga County's first strip malls, complete with Solvay's prettiest and most comfortable movie theater, was built kitty-corner across the street from the ill-fated gasoline station. Although it was on the southern border of the village, it became downtown Solvay, though it lacked the bars that lined Milton Avenue at the northern edge of the village. Today the glory days of the Westvale Plaza and the Genesee Theater are long gone, though the plaza, at least, is still open for business. The theater closed many years ago. MY TAKE on the James Bixby murder no doubt is influenced by the fact I watch entirely too many police shows. I also was goaded by a column written by Syracuse Journal editor Harvey Burrill (August 14, 1930). Using the Bixby shooting as an example, Burrill made this comment, albeit about the Syracuse police force, not the others who were investigating the case: "It is clearly evident that officers are slow in responding and rather dumb in their actions." While police — particularly the state police — were looking toward Auburn, I thought everyone missed the obvious likelihood that the man they were looking for lived within walking distance of the gasoline station and was familiar with the people who worked there. There is no mention of how he arrived for his first two robberies, only that on both occasions he stole cars that belonged to station employees. On his third visit — when the only attendant on duty was Bixby, who lived so close to the station that he almost certainly walked to work — the thief arrived in a stolen taxi cab. When he entered the cab in downtown Syracuse, he told the driver to take him to the 1800 block of West Genesee Street, which is about two blocks from the gasoline station I doubt whether someone from Auburn, Weedsport or even most areas of Syracuse could have been so specific about a location on West Genesee Street. Also, twice he had to escape on foot and wasn't seen, likely wouldn't have tried to hitch a ride on a busy street, and did not steal a car. I think he simply walked home. Finally, maybe the man who provided a ride in July stopped at the gasoline station because it was close to where the hitchhiker wanted to be dropped off. Maybe the hitchhiker wasn't the robber. Gasoline station attendant Don Schultz wasn't exactly spot-on as an eyewitness. The man who killed James Bixby is undoubtedly dead — or one of the world's oldest living men. Perhaps he served time for other crimes, perhaps he decided he pushed his luck too far and got himself a real job. And perhaps, during the many evenings I spent watching movies at the Genesee Theater, the murderer was munching pop corn in a nearby row. |

|

| For more on Solvay way back when, check out the Solvay-Geddes Historical Society |

|

| HOME | CONTACT |

The statement Bixby made in St. Joseph Hospital to clerk Charles Edick was the first tangible clue furnished police on which to base their hunt for the bandit who held up a taxi driver, stole his machine and then attempted to stick up the gasoline station early this morning.

The statement Bixby made in St. Joseph Hospital to clerk Charles Edick was the first tangible clue furnished police on which to base their hunt for the bandit who held up a taxi driver, stole his machine and then attempted to stick up the gasoline station early this morning. officials started legal machinery in motion to conduct a full investigation of the startling acknowledgment of guilty, which, if substantiated, will bring Starowicz to trial on a charge of murder in the first degree.

officials started legal machinery in motion to conduct a full investigation of the startling acknowledgment of guilty, which, if substantiated, will bring Starowicz to trial on a charge of murder in the first degree.