| HOME |

|

|

|

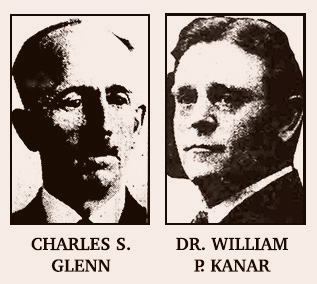

The village election of 1916 very likely was the craziest in Solvay history. The two candidates for president — which is the title given in those days to the position known today as mayor — each received 514 votes. The problem: How to settle the tie. Here's how they did it about a week after the election: |

|

|

|

The coin toss was only part of the reason this election was so unusual. Immediately after the results were tallied on March 21, Republicans challenged two ballots they said were invalid. Both ballots contained votes for Charles Glenn and for Democratic trustee candidate Francis Worth, who was elected by one vote. Had one of those ballots been tossed out, then Dr. Kanar would have been elected mayor, but there would be a tie to decide the outcome of the third trustee position. Not simply a two-way tie, but a three-way tie. Republicans George Haas and William Welch each received 474 votes, one less than Worth. And even if both contested ballots were declared invalid, there would still be a tie that needed settling, this one between two Republicans. UNTIL 1909, Solvay's village board was comprised by four trustees. Ever since there have been six trustees. Interestingly, in 1916, the trustees each served a two-year term; the president served only a one-year term. (Now called the mayor, the chief executive of the village serves a four-year term; trustees still serve two-year terms.) Making matters more complicated in 1916 (and all the years before) was that the trustee winners were the three candidates who received the most votes, regardless of where they lived in the village. That would be changed a few years later when Solvay was divided into three wards, each represented by two trustees. This was not the first time Dr. Kanar's election as mayor was in doubt. He made his first bid for the office five years earlier. Though running as a Republican, the doctor, until then, was considered a Democrat, which may be why he fared so Worth was a carpenter and contractor, who, in 1909, made village history when he became the first Democrat elected president. The man he defeated was Frederick R. Hazard, who also was president of the Solvay Process Company, and the lord of the manor known as the Hazard Estate, which contained the two largest homes in the village, the main building standing like a castle along Orchard Road at the southern edge of the village. Until 1909, Hazard was the only president in the 15-year history of Solvay. WORTH WAS re-elected three times, doing it unopposed in 1912, and was expected to win when Republicans nominated Dr. Kanar again in 1913, but there was an upset, and no one disputed that Dr. Kanar received more votes. However, Police Justice William Ryan, recognized as the boss of the Democratic party in the town of Geddes, claimed Kanar wasn't eligible to hold office because a section of the village law provided that a president, at the time of his election must be the owner of property assessed to him on the last preceding assessment roll. Dr. Kanar owned a house in the middle of the village at 404 North Orchard Road, but for reasons not explained in any story I found, the property was listed in his wife's name, and assessed to her on the most recent tax roll. Dr. Kanar had taken steps to list the house in his name, but he did this eight months too late, according to Judge Ryan. But it was another judge, State Supreme Court Justice Irving G. Hubbs, who had the final say in the matter, and he ruled in favor of Dr. Kanar, This ruling came almost two months after the election. In the meantime, it was Solvay politics as usual: |

|

|

|

Four nights later, at the regularly scheduled Tuesday night meeting of the village board, Dr. Kanar and the two Republican trustees, arrived early, but for awhile it looked as though the four Democrat trustees would be no-shows. One of them was needed for a quorum. Finally, Charles S. Glenn arrived, and agreed to participate, on condition only routine business would be transacted. Dr. Kanar and his colleagues agreed there would be no more meetings until the status of Dr. Kanar's eligibility was decided. The Democratic trustee with my name, John Major, was my grandfather. Agreed, this was not his finest hour as a politician. His son (and my father), Stanley "Buster" Major, would be elected mayor of Solvay in 1949. He, too, would be elected with two Democrat trustees, constituting a three-to-four minority on the village board. (They'd gain control a year later.) During his first summer in office, my father was involved in a very strange village board meeting when one of the Republican trustees didn't attend. He was out of town on vacation. SO THERE they sat — three Democrats and three Republicans — and the Democrats refused to adjourn the meeting after one of the Republicans moved to do so. The plan, silly as it may seem, was to stay in session in case one of the Republicans had to leave (before turning into a pumpkin at midnight, I suppose). An absent Republican would give the Democrats a three-to-two advantage, which they were sure to use to approve certain items. Why all three of the Republicans didn't bolt, I'm not sure, unless there was some weird provision in the by-laws that a quorum was needed only to start a meeting, and once started, it could continue without a quorum. Long story short, that particular meeting continued long after midnight. Anyway, Dr. Kanar was unquestionably the Solvay president from the middle of May, and the following March — I don't know why, but village elections in New York State are held in March — he was re-elected, defeating Democrat Charles Johnson and Solvay High School Principal Claude A. Duvall, candidate of the Prohibition party, which emerged for a while during the period leading up to 1920. In August, 1914, President Kanar faced an issue that had been a sore point with several village presidents and mayors over the years — water. |

|

|

|

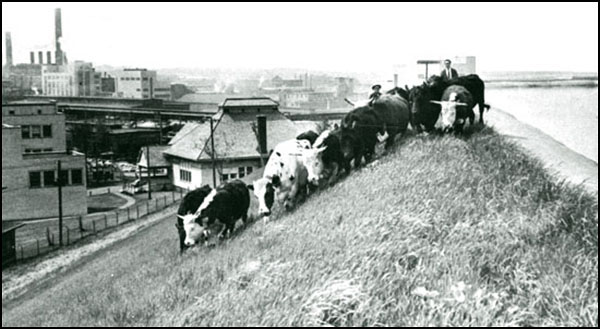

A book could be written about the sources and consequences of Solvay's drinking water, from an underground stream, originally used, to the Otisco Lake water which served the village for many years, to the time the head of the water and light department in my father's administration re-discovered the underground stream and mixed its with the Otisco Lake water (for which Mayor "Buster" Major was severely criticized) to when the village was forced to abandon Otisco Lake and get its water from Lake Ontario (which is when I opted for bottled water during my visits home). Back to the cattle near the reservoir . . . The Solvay reservoir was atop a hill on the southern edge of the village, and not to be confused with a separate Solvay Process reservoir in the northeast corner of the village near the intersection of Milton and Emerson avenues. (See bottom of the page.) While the Solvay Process Company intentionally brought in sheep, then cows, to eat the grass around the reservoir, thus eliminating a potentially dangerous mowing job, the cattle near the village reservoir in the early days of the village probably were part of a herd owned by a man who lived on West Genesee Street, which the reservoir overlooked. Hard to believe today, but at the time there was a cattle ranch a stone's throw from Solvay. DR. KANAR weathered the criticism about the water and comfortably won re-election in 1915, defeating Frederick J. Darrow. A year later came the tie, probably due more to the popularity of his opponent, Charles S. Glenn, than any problem Dr. Kanar was having with the electorate, because in 1917 he was elected without opposition. So was Edwin M. Hall, a Democrat who ran for village clerk. The big change in the 1918 election was that women cast their first ballots, something they would do for the first time in a United States presidential election two years later. In 1918, an estimated 600 women voted in Solvay, out of 1,747 votes cast. Dr. Kanar defeated his Democratic opponent, Thomas Murphy, 929 to 683. Otherwise, it was a year of bad news — the United States was involved in World War One, and an outbreak of Spanish flu that fall was devastatingly deadly, forcing the closing of all public places in an attempt to slow the spread of the disease. The disease was worldwide; estimates are it was responsible for at least 50 million deaths, possibly as many as 100 million. WHATEVER the factors — lingering effects of the war and the flu epidemic, or simply a job well done — Dr. Kanar faced little political opposition for the next three years, running unopposed in 1919 and easily winning the 1920 election against his Democratic opponent, Michael G. Linsky. However, Solvay's big political news in 1920 was the nomination — and election — of two women candidates, Mrs. Bernice R. Stanton for village treasurer and Mrs. Zora M. Herrick for village collector. They were two of only three Democrats to win in March. The other was Edwin Hall for village clerk, who ran unopposed. Mrs. Stanton defeated Howard B. Bryant, while Mrs. Herrick defeated Michael F. Brown. Both men were on the Republican ticket. In 1921, Solvay Democrats nominated William T. Kulle to run for president, but he removed himself from the ticket about two weeks before the election, so Dr. Kanar again was unopposed. There was no reason given for Kulle's decision, but it may be that he changed his residence, making him ineligible, since most stories I found on him afterward were in a Baldwinsville newspaper, which said Kulle lived in Belle Isle, just outside of the Solvay village limits. A HOT ISSUE across the nation in 1921 was daylight savings time, strongly opposed by farmers, but endorsed by residents of most cities. What made it complicated was that it was up to each municipality, no matter how small, to decide whether to adopt daylight savings. Syracuse adopted it and Dr. Kanar announced Solvay was following suit. "It would be folly," he said, "not to follow the lead of Syracuse in this respect." Some communities voted against daylight savings time. The result was often confusing as people could lose an hour, gain it back, and lose it again as they traveled from town to town. (Though incorporated as a village, and never, I think, having a population more than 8,700, Solvay had little in common with its rural neighbors, and because of its wall-to-wall factories along Milton Avenue seemed very much like a city.) An important matter to Solvay residents in 1921 was the overcrowding of Boyd School, one of two elementary schools in the village. It became necessary to transfer 80 students from Boyd to Prospect School, putting them in rooms in the basement that weren't originally intended for classes. Two extra teachers were hired. THIS TOUCHED upon the east-west rivalry that also was an unusual feature of Solvay life. It probably began when the Hazard family, which included the first two presidents of the Solvay Process Company, bought land which extended from the factory on Milton Avenue to the southern border of the village on West Genesee Street. This land became the Hazard Estate, and the street that ran through it was called Orchard Road, later North Orchard Road to separate it from the continuation of the road across West Genesee Street (N. Y. Route 5) into the section of the Town of Geddes known as Westvale. Residences and businesses in the village were thus divided into East Solvay and West Solvay, and the line between them became blurred over time as the Hazard family sold off or donated land, particularly on the west side of Orchard Road. Dr. Kanar, for example, bought a house at 404 North Orchard Road. Ask people who lived in Solvay in the 1950s to tell you where East Solvay ends and West Solvay begins, you're likely to receive a different answer every time. One thing was clear: Children who attended Boyd School knew they lived in West Solvay; those at Prospect School were from East Solvay. It must have upset those 80 West Solvay students when they were told about their arbitrary transfer to Prospect School. The situation prompted a proposal to build a new high school, which would be opposed by (of all people) members of the board of education. Dr. Kanar and the village board of trustees endorsed the idea, and the school would be built, with the old high school eventually converted into a middle school. (Apparently, for a few years after it was built, the new facility was a junior-senior high school.) DR. KANAR was president long enough to speak out in favor of a new high school, but was defeated in March, 1922, by the man he had bested nine years before — Francis L. Worth, making an unusual comeback. Worth received 1,138 votes, Dr. Kanar 829. All three Democratic trustee candidates — Edward J. Jutton, Edward C. Chamberlain and John C. Hardy — were victorious. Mrs. Bernice A. Stanton, treasurer, and Edwin M. Hall, clerk, were unopposed. Interestingly, Worth was a member of the board of education that had come out against the new high school. However, the chairman of the school board was the first president of the village. Frederick R. Hazard, who not only disagreed with school board members, but had donated the land upon which the new high school would be built. He carried the big stick, threatening to quit the board of education unless . . . (The street upon which that school was built was named Hazard Street. Also, the land for the high school was on the southern edge of the village, safely away from the East Solvay-West Solvay battlegrounds closer to Milton Avenue. The high school also abutted the Piercefield area, which wasn't annexed by the village until 1927.) In 1923, Worth won re-election, defeating Republican William Tindall by 217 votes. Democrats won every race except in the second ward where Republican Orlow Joslin was elected trustee over Lawrence J. Bennett. Voters also approved of three propositions for improvements that would total $200,000. Among them: a new fire house. Statewide, a measure to increase the minimum speed limit from 15 miles per hour to 20 was passed. FRANCIS L. WORTH announced early in 1924 that he was leaving Solvay, heeding the words of Horace Greeley to go west. Worth, at 54 years of age, moved to Alhambra, California, where he re-located his contracting business. In his place, Democrats nominated Charles R. Hall for president. Hall was a long-time employee of New York Central, and was the ticket agent at the Solvay depot. Perhaps sensing that he could make a comeback, Dr. William P. Kanar sought and received the Republican nomination for president, but Hall won the election, as did every Democratic candidate but one. Republican Michael A. Baratta became the trustee from the second ward, defeating Edward J. Jutton. On April 11, 1924, Worth made his last public appearance in Solvay, turning the first shovelful of dirt to mark the start of construction on the new high school building. In addition to being president of the village, Worth had remained a member of the school board, retiring when he made his announcement about moving to California. In 1925, Charles R. Hall was re-elected president of the village, this time defeating Republican candidate Clarence Paltz. A year later, Hall would win again, defeating Howard B. Bryant. On May 10, 1926, two months after the election, Dr. William P. Kanar passed away. He was 60 years old. He had been ill for two years. Dr. Kanar lived in Hannibal, New York, before moving to Solvay about 1895, the year he married Miss Franc Brackett, whom he met in Hannibal. Tragically, she died just four years later, at the age of 31. In 1908, Dr. Kanar, then 42, married Miss Margaret Edythe Ryder of Solvay. They lived for awhile at 517 Milton Avenue before moving to 404 North Orchard Road. My guess is Dr. Kanar was able to buy property on what was the fringe of the Hazard Estate because of his connection with the Solvay Process Company where he was on call as the company physician. Being president of the village was a part-time job, and his full-time occupation sometimes place Dr. Kanar in unusual situations. For example, one of the most popular annual events in Solvay was the Feast of the Assumption celebration that took place in August at Woods Road Park, near St. Cecilia's Church. This was a carnival, highlighted by a late night fireworks display that drew large crowds. In 1921, members of this crowd became unruly, and a fight broke out between some men who didn't like the band that was performing, and some men who thought the music was just fine. Knives and razors were drawn, and a free-for-all erupted. Men were injured, others arrested. And while village police restored order, the wounded were attended by the village president. |

|

|

| HOME | CONTACT |

provision that a tie should be decided by lot. The suggestion was adopted unanimously.

provision that a tie should be decided by lot. The suggestion was adopted unanimously. poorly in 1911. Francis L. Worth, the same man elected a trustee in 1916, was the incumbent mayor in 1911, and he received 56 percent of the vote that year.

poorly in 1911. Francis L. Worth, the same man elected a trustee in 1916, was the incumbent mayor in 1911, and he received 56 percent of the vote that year.