| HOME |

|

|

|

|

|

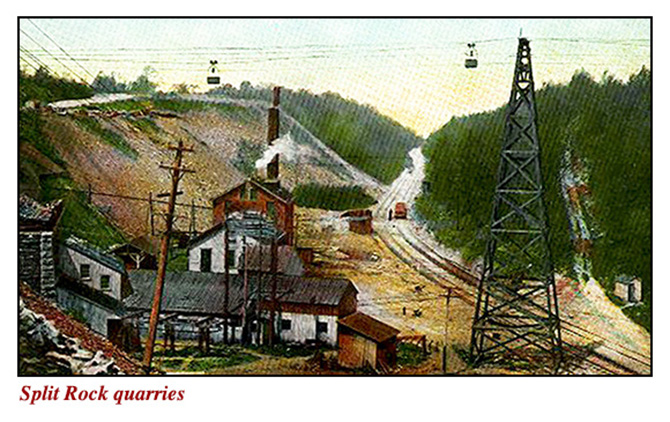

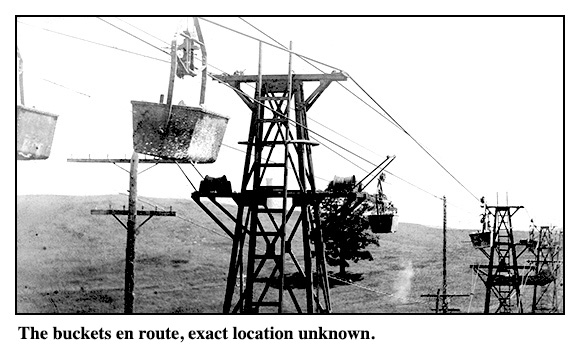

A Solvay Process Company publication — year unknown; best guess: 1950 — referred to the cable line that carried buckets from the Split Rock limestone quarries to the factory in Solvay as "a marvel of engineering genius." And for 23 years, these buckets,, which soared from south end of the village to the north end, supplied Solvay Process with the limestone that was essential to the operation. The company publication says the distance between the quarries and the factory was eight miles. The story below says the cable line covered three-and-a-quarter miles. I think the actual distance was somewhere in between. In any case, the bucket line was one of the most interesting things about the early days of the Solvay Process Company, which was the reason for the existence of my hometown. |

|

|

|

Perhaps not yet realizing it factory would, in the near future, receive its limestone from a different source, the Solvay Process Company, in 1908, completed an improvement on its bucket system that allowed it to operate entirely through gravity, eliminating the need for a steam engine at the lime kiln building. Until this project was finished, the buckets did not have a downhill ride all the way from Split Rock to the factory in Solvay. The one obstacle was a hill that stood between the end of Cogswell Avenue and West Genesee Street. When the following job was finished, the buckets could go through the hill. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

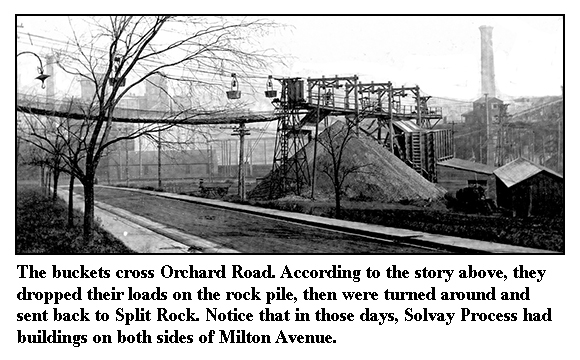

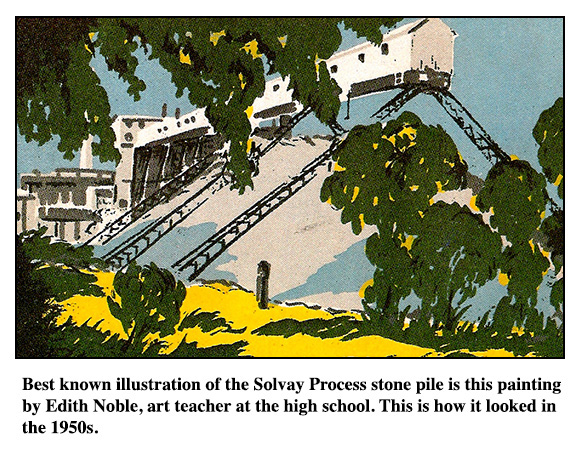

I grew up on Russet Lane, a dead-end street that intersected with Orchard Road at the top of the incline from Milton Avenue. Most of the backyards on the north side of Russet Lane faced the village hill that was closest to the Solvay Process. So the buckets in the above photo are either coming from or going back toward the hill that figured a lot in my childhood. By the time I was born (1938), the bucket line was long gone. As I recall, there was a reminder on the hill in the form of four concrete blocks from the foundation of the structure that supported the bucket line cables. I think it must have been those blocks that prompted my father to tell me about the buckets that delivered limestone to the Solvay Process. There were four hills within the village that were affected by the bucket line, the highest being the southernmost between the top of Cogswell Avenue and West Genesee Street, called the Genesee Turnpike back then. I never took the time to picture the bucket line between the village and the quarries at Split Rock, except I knew, from driving through Split Rock as a teenager, that the quarries were considerably higher than the hill behind my house. I don't think Russet Lane existed during World War One, but years later, during the Second World War, some residents of our street were encouraged by the Solvay Process to use the hill — which the company owned — to plant Victory Gardens. That was my introduction to the hill, going with my parents to check the progress of our tomatoes, potatoes, peas and string beans. There's more about the hill in my recollections of Russet Lane. When my father told me about the bucket line, he said that he and his friends used to climb aboard the empty buckets as they passed over one hill (where the buckets were just inches off the ground) and ride to the next hill, or the one after that. At the time my father first mentioned this, I was unaware of the history of the bucket line and didn't consider some facts about my father's childhood. I have no doubt my father was telling the truth, but for him to take a ride in a bucket, he would have had to do it before his ninth birthday. Since he hung around with his brother, Billy, who was three years older, it's believable to think my father accepted a dare, even when he was six or seven years old. He was like that, and kids in those days did some fairly wild things, like dive off a railroad bridge into the Erie Canal, where my father and his brother did a lot of their swimming. The Majors lived on Alice Avenue, deep in the heart of West Solvay, so it's likely their bucket rides started atop one of the two hills between Russet Lane and the one at the southern edge of the village. My father claimed that before he and his friends jumped off the buckets, they would ride the buckets through the tunnel that was built in 1908. This wasn't legal, of course, and it was very dangerous, but it also was how children amused themselves in those days. Some of the same spirit existed 40 years later when I was a young boy, though I never took the risks that my father and his friends did. About the dumbest thing I ever did was after my mother made me a parachute — Why? I can't remember — and I tested it by jumping off our front porch. |

|

|

| HOME | CONTACT |