| HOME |

|

|

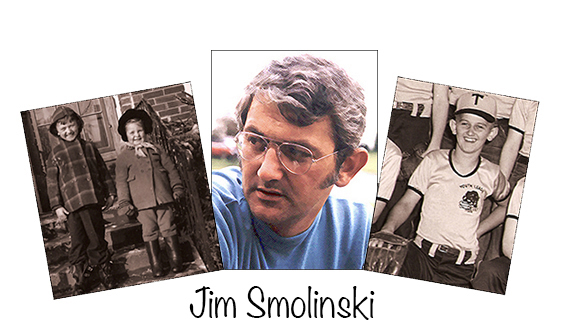

He usually had the last laugh Of the four Smolinski cousins next door, Jimmy was the closest to me in age. I was a couple of years older, my sister, Mary, was three years younger than Jimmy. Sometimes it seemed he was the middle child in our family. He certainly fit right in because he got along with Mary much better in those days than I did. What I remember about Jimmy as a youngster is that he was clever and very funny. Like baseball's Pee Wee Reese Jimmy wasn't small — when he stopped growing (after a remarkable spurt during his high school years) — he was about six-feet tall. Jimmy graduated from Solvay High School when he was 16. For reasons I never understood, Jimmy went speeding through high school, going to summer school for extra credits that pushed his graduation up a year. And then, as I recall, he took a year off from school before entering LeMoyne College. MY FAVORITE anecdotes about Jimmy probably won't mean much to others, though to me they touch on various aspects of his personality and manner. Like the time I was maybe 11 or 12 and Jimmy challenged me to a footrace down Russet Lane, and I took the bait. He led me to what he had designated as the starting line, the coolly suggested we switch directions. So I turned around and assumed a starting position while he counted down to "Go!" Seconds later I was off, thinking I had indeed left the tortoise in the dust. He was nowhere in sight ... but I could hear him, which is when I knew I'd been had. I stopped, turned around, and saw Jimmy walking toward his house. He looked at me, smiled, and gave me a dismissive wave ... as though he'd just won a bet that he could make his cousin run lickety-split down the street for no good reason. Jimmy and I played baseball in the Solvay Tigers Youth League, our village's answer to Little League. One year we were teammates, the next we were competitors. Jimmy was a promising athlete, which was expected because the oldest Smolinski brother, Bimby, had played high school baseball and was one of the best basketball players in Onondaga County. Jimmy's other older brother, Bobby, who stood six-feet-seven-inches, played football and basketball at Solvay High, then was the center on the LeMoyne College basketball team. Jimmy was more like Bimby than Bobby, but while Bimby had played shortstop on the baseball team, Jimmy was so versatile he'd play anywhere, even catcher, the hardest, but most important position there is in youth leagues (where pitchers are only as good as the kid behind the plate). Jimmy also pitched occasionally, which gave him an essential role in an incident that provided one of my favorite memories. As I explain it, you'll most likely think — perhaps correctly — that this is all about me, but those who knew Jimmy, especially those who knew him way back when, may conclude that once again he had set me up. It happened during my third and final Solvay Tigers season. I was 15 at the time, which means Jimmy was 13. I didn't know it, but I had reached my full height — stopping just shy of six-feet-four inches. I was the tallest kid in the league. If I had played in Little League I would have been the kid whose birth certificate was questioned by every coach in the league. I hit a few home more runs during the first two seasons, and in year three I was put on a team coached by a guy named Red Falkowski. At 15, facing some pitchers who were two years younger, Falkowski figured I'd be a regular Babe Ruth. Instead I went through the season as though I were sleep-walking. Seldom did I hit a ball past the infield, and most of those grounders went toward shortstop, not a good thing since I'm a left-handed hitter. Obviously, the coach wasn't pleased. ENTER JIMMY. He's the opposing pitcher in the last game of the season. I'm at bat and Red Falkowski is yelling at me from the third base coach's box. "I expected more of you, Major! I expected home runs and you haven't hit one all season!" I didn't often step out of the batter's box, but this time I did. I don't know what possessed me, though I wasn't surprised at my behavior because, frankly, I didn't like the coach, so I yelled back, "You want a home run? Well, here it comes!" Jimmy watched all of this from the mound, of course, and considered his options. He could try to make an idiot of his cousin by striking me out on his best stuff — I couldn't hit a curve worth diddly — or he could deliberately groove his first pitch, giving his cousin an opportunity to make good on his boast. If I swung and missed, well, he'd never let me forget it. I swear Jimmy was grinning when he threw the pitch, but seconds later all I could think about was the result — the best hit of my entire life, before or since. I could have walked around the bases. Twice, maybe three times. The ball landed out of sight over the crest of a hill in right field. The right and center fielders went after the ball which bounced and rolled a considerable distance until it stopped in some tall grass behind one of the backyards on Russet Lane. Jimmy and I often mentioned the incident to each other over the years, but never analyzed it. Maybe it just happened, but I suspect the result was something Jimmy wanted as much as I did. Besides, he owed me one for that footrace stunt. Thanks to my father being (1) the mayor of Solvay, (2) a well-known local athlete and (3) a long-time Solvay Process employee, he arranged for my basketball team, a group of neighborhood boys, to use the Solvay High School gymnasium on those evenings the Process team had a home game. The Solvay Process played in a league that featured an assortment of town and company teams, and at least once took on a squad comprised of Syracuse University football players. My team played the preliminary game. Jimmy Smolinski was on my team; he was probably 10 or 11 at the time, since I couldn't have been older than 13. We played anyone our age who'd agree to show up, though most of our games were against a team representing Robinson Memorial Presbyterian Church in Westvale which featured a few boys who'd later be my teammates at Solvay High. I can't recall who officiated the games, but we had someone keeping score, which is the important part of this story. Jimmy played several minutes in each game, though he went scoreless through the first three or four. Finally he made his first basket, but rather than hustle back on defense, Jimmy ran to the scorer's table to make sure he was credited with two points. As I recall, he penciled it in himself. HE WAS a starter on the Solvay Tigers Biddy League team that went to the first national Biddy League championship tournament in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He was 12 that year; I was 14 and playing on another Tigers team, one that played in a league at the Syracuse Boys Club. That season we were visited by Al Cervi, player-coach of the Syracuse Nationals of the National Basketball Association, and Dolph Schayes, the team's star player. They spent a couple of hours instructing us on various phases of the game, and Cervi singled out Jimmy for praise several times. At the end of the Biddy League season there was a local tournament to decide who was going to compete in Scranton. My memory, as it is with all of the recollections on this website, may not be completely accurate, but I believe there was much confusion during that tournament, a one-day affair that was the first of its kind in Syracuse. At least one coach was unaware that if his team kept winning it would be required to play three games that afternoon. That one coach, as I recall, refused to allow his boys to play in the championship game unless it was scheduled another day. The Solvay Tigers were willing to play and they were awarded the championship and a trip to the national tournament. That, I believe, was the second point of confusion. What they were expecting in Scranton was an all-star team from the Syracuse area with the players from several teams chosen on the basis of their performance in the local tournament. IN ANY EVENT, Jimmy Smolinski would have gone to Scranton because Al Cervi attended the tournament and it was his job to pick a most valuable player. Though Jimmy was not his team's top scorer, Cervi felt he had contributed the most to his team's success. The team lost its first game in Scranton, which put it in the loser's bracket in the eight-team tournament. I believe they won their next two games to finish fifth. The winners, a team from Peoria, Illinois, were the only ones to defeat the Tigers. Apparently the tournament organizers, while disappointed that Syracuse had not sent an all-star team, were very impressed at the Tigers' showing. Jimmy went on to play at Solvay High School and during the 1954-55 season was a member of the junior varsity team that went undefeated in league play before suffering its only loss, 31-29 to Marcellus, in the Onondaga County Championship Game. Jimmy and I went our separate ways, me to Ohio and Jimmy to Grafton, Massachusetts, where he lived with his first wife, Avril Judson Smolinski, her daughter, Alison Wilson, and their two children, James and Elizabeth Smolinski. Jimmy and I did catch up with each other a couple of times after I moved to Rhode Island, but Jimmy moved back to Solvay after he and Avril divorced. In 1996 Jimmy married Joanne H. O'Connor and his son, James, was the best man. Joanne had five children by her first marriage. Jimmy retired several ago from his job in sales at Lewis Goodman, Inc., though for awhile he filled in occasionally. Sadly, in 2016, Joanne died, and Jimmy carried on alone, plagued by health problems until his own passing. If this story went on a bit longer than the others, well, that also suit Jimmy just fine. When I called him several years ago to ask for a photo or two (which never arrived), he said it was around time I contacted him. "After all, I should be the star of that website." So he is. |

| — JACK MAJOR |

| HOME | CONTACT |