| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

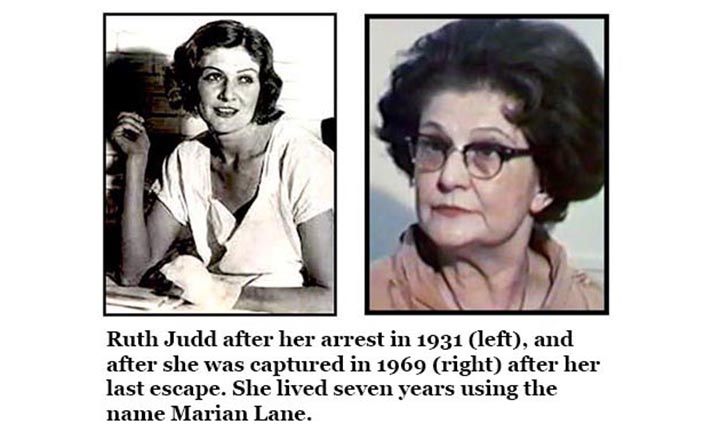

by JACK MAJOR There aren't many people today who can identify the once-notorious Ruth Judd, responsible for 1931's famous "Trunk Murders." She died in 1998 at the age of 93. Not bad for a woman who was supposed to be hanged a few weeks after her 28th birthday. Her parents, the Rev. Harvey Joy McKinnell and Carrie Belle Niswonger McKinnell, named her Winifred Ruth, but they needn't have bothered with the first name. Winifred became Winnie, then pretty much disappeared until newspapers brought it back in 1931 by insisting in every article the woman accused of killing her "two best friends" was known to those friends as Winnie Ruth Judd. One newspaper even claimed those friends called her "Winsome Winnie." ("Ruthless Ruthie" would have been more appropriate.) In truth, the murderer was known to friends and family as Ruth. The proof is on a controversial confession letter she wrote to one of her lawyers in 1933 — she signed every one of the 19 pages as Ruth Judd. Her parents called her Ruth, her brother called her Ruth, and, in a letter, one of her future victims told her parents about a woman named "Ruth Judd," while the other woman she murdered addressed her as "Ruthie." But when Los Angeles police booked her in 1931, they identified her as Winnie Ruth Judd. That's how she signed the sheet. and how most newspapers identified her thereafter. Her last name had changed in 1924 when she married Dr. William C. Judd. But after the sensational 1931 murders, the 26-year-old medical secretary picked up several nicknames — "Tiger Woman," "Wolfwoman," "The Trunk Murderess," "The Blonde Enigma," "The Blonde Butcher," and worse. "Tiger Woman" became the media favorite, probably because it had been a popular nickname for evil women since 1917 when Theda Bara, the famous Hollywood vamp, starred in a movie called "The Tiger Woman." As far as I know, the first woman murderer to be called "Tiger Woman" was Clara Phillips, who, in a fit of misguided jealousy in 1922, killed Alberta Meadows by savagely beating her with a claw hammer, mostly using the claw side. That murder occurred in Los Angeles, so when Ruth Judd's two victims showed up in La La Land nine years later, newspapers there couldn't help dubbing her "Tiger Woman." (I'm surprised some Los Angeles newspapers didn't say, "Tiger Woman 2," "Tiger Woman, Too" or "Tiger Woman: The Sequel.") Soon to become almost afterthoughts were Ruth Judd's victims — Agnes Anne Imlah LeRoi and Sarah Hedvig "Sammy" Samuelson. Mrs. Judd dismembered Ms. Samuelson, and packed the pieces in a trunk, a suitcase, and a hat box, and put her other victim in a larger trunk, before shipping the luggage from Phoenix, Arizona, to Los Angeles aboard a train. Whether Ruth Judd was on that train or took one that arrived earlier depends on what story you read. Not that it makes any difference. What you believe about this case depends on what stories you read. Much has been written about Ruth Judd, and one woman, who researched the case for a book published in 1998, concluded Mrs. Judd didn't kill anyone, but that author, Jana Bommersbach, and anyone who agrees with her theory, are wrong. Dead wrong. Without reading her book, you can get the gist of it from other writers. I don't believe their versions of the murders, or that any political chicanery was involved. I don't think the man involved with the three women — a lumber salesman named Jack Halloran — was nearly the mover and shaker some have claimed. This case was much simpler than the one Ms. Bommersbach and others have described. Ruth Judd was nursing a grudge, and it got out of hand. What happened next is all on her, despite rebuttals skeptics may offer. Admittedly, there are reasons to question whether Ruth Judd had the strength to commit these horrible murders all by herself, but, trust me, she did. Nothing else makes sense. She alone wanted Mrs. LeRoi dead. Ms. Samuelson was collateral damage — maybe — but something that happened when "Sammy" confronted her is what convinced me Ruth Judd had no help, although this "something" made the dissecting job painfully difficult. This will be explained later. What I don't understand is how this "something" could have been overlooked or misinterpreted by people who came up with alternate scenarios of the crime. Let's go back to October 19, 1931, and start Ruth Judd's story in the middle — on the day Ruth Judd arrived in Los Angeles: |

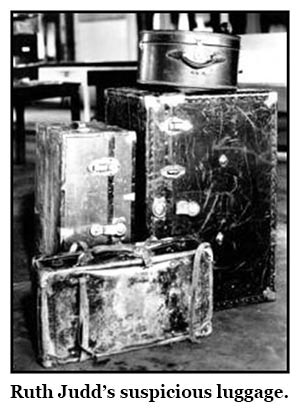

Lady, what's oozing out of this trunk? “This girl probably was twenty-five, with a porcelain clarity of skin that placed her as a member of one of the tuberculosis colonies out on the dessert. She had copper-colored hair and large, curiously pale blue eyes.” Ruth Judd had been dealing with tuberculosis for several years. That's why she had been living in Phoenix. She was slim — five-foot-six, 108 pounds — with an attractive face that often seemed tired or stressed. (In photos, she usually seemed about ten years older than her actual age.) Los Angeles baggageman Arthur Henderson immediately raised her stress level, because he wouldn't release the luggage until he looked inside the larger of two trunks. He noticed blood was seeping out. Henderson's first suspicion was the Mrs. Judd obviously was nervous, but showed remarkable calm and ingenuity, saying, by golly, she didn't have the key to the trunk, and would have to call her husband. There was a young man with her, but he was her brother, Burton McKinnell, a junior at the University of Southern California, who wasn't sure what was in his sister's luggage, but had his suspicions. He didn't know his sister would be in Los Angeles until — and this is another multiple choice element of the case — she sent him a telegram from Phoniz the night before, or called him after she arrived in the city. THE PATIENT Henderson waited four hours before he called police. By that time, Mrs. Judd and her brother had gone their separate ways after he dropped her off in the downtown area and gave her his last five dollars, plus change. One reason to believe Ruth Judd had no partner or accomplices is that she arrived in Los Angeles penniless. Another reason is the way she attempted to dispose of the bodies. She had no plan beyond getting them aboard a train, and convincing her brother to take the trunks to the ocean and dump them in deep water. And it's not like he had a boat at his disposal. Had Ruth Judd been in league with anyone with half a brain, it would have been more logically suggested to dump the bodies in the desert outside of Phoenix, then a small city of about 50,000 residents. Thanks to the baggageman, the bodies were out of Ruth Judd's hands, so she went into hiding and didn't surface for five days, though there were false sitings of the fugitive all over the western half of the country. Newspapers all over the country jumped on this story, which wouldn't have happened if Mrs. Judd had disposed of the bodies in the desolate Phoenix outskirts, but putting them in suitcases for a train ride to Los Angeles ... that was crazy enough to make everyone take notice. Ah, but was Ruth Judd really crazy? That would be the most debated question in this case. In the meantime, she was instantly famous as "The Trunk Murderess." "Tiger Woman" soon followed. |

Strange marriage, strange case Dr. Judd had worked in Phoenix for awhile in 1920, about three years before he moved to Indiana, where he met Ruth McKinnell. Soon after he and Ruth were married in 1924, he took a job in Mexico; from there they moved to Los Angeles. Her knowledge of the city came back to help her in 1931, and she survived on her own before hunger and a painful gunshot wound in her left hand prompted her to surrender to the police. She had also noticed a message from her husband, printed in a Los Angeles newspaper. It urged her to turn herself in. By then, she had concocted a self-defense story. Meanwhile, the press was kicking around more sensational versions of the case. The immediate reaction in Los Angeles was Mrs. Judd and her two victims made up a lesbian triangle, though newspapers substituted the word "strange" for "lesbian." The murders were compared to one a year earlier in Laguna Beach when a woman killed her longtime companion, then committed suicide. However, the press and police soon learned Mrs. Judd and her two victims were all involved with the same man, a lumber dealer who had a wife and three children. Was he somehow involved in the murders? But after Ruth Judd turned herself in, she rather quickly confessed, saying she had acted alone — in self-defense. She was taken to a hospital to have a bullet slug removed from her left hand. This bullet wound and when the slug was removed is what undercuts every argument that Ruth Judd didn't kill anyone, or she had help either during or after the crime, particularly in dismembering a body. I'll explain my reasoning later. Mrs. Judd's self-defense story would slightly change with each telling, and within days she was telling it a lot. Every newspaper in Los Angeles — and in those days there were newspapers galore — was running Winnie Ruth Judd's own story, in her own words. Some newspapers paid her, some didn't. On December 16, 1931, it was reported in the Nogales (Arizona) International that Mrs. Judd collected more than $20,000 from publications for her various "confessions." THE MORE I read about Ruth Judd, the more fascinated I became, partly because I've always found the 1920s and '30s interesting, and because Mrs. Judd had a knack for twisting truth in such a way I began to suspect she was related to Donald Trump. Like Trump, Mrs. Judd passed herself off as the victim, and the real victims were soon forgotten. What motivated this article was the now infamous confession letter Ruth Judd wrote over two days in 1933 and gave to her lawyer, who decided not to use it during her sanity trial. She had been convicted and sentenced to die. If she were judged sane, the execution would go ahead as planned. The lawyer felt the letter would hurt Mrs. Judd's case, so he stuck it in a drawer, and it didn't become public for 81 years. While still self-serving in spots, this long letter, I believe, is the closest Ruth Judd ever came to telling the truth about the murders. But the letter was written by a woman who obviously was sane, so lawyer H. G. Richardson tucked it away. That turned out to be a smart move on Richardson's part; assisted by a colorful performance by his client, Richardson convinced an Arizona jury Mrs. Judd was insane, and she survived to live another 65 years, much of it in an institution from which she would escape several times. It was Richardson's refusal to use the letter that convinced me it was basically true. Also interesting is that three months before this confession, Ruth Judd made a desperate attempt to involve her former lover as her accomplice. When this failed, I believe she decided, at last, to make an effort to be truthful. She didn't quite succeed, but I think she came close. For the most part, her 1933 confession is supported by witness statements and police findings, though Ruth Judd still presented herself as a victim. In addition to the letter, I also read a ton of interesting newspaper articles for information that's included here. To repeat the well-worn line from countless films, this is my story, and I'm sticking to it. Let's meet my story's leading characters: |

When first questioned by police about the murders, Dr. Judd said he was born in Gibson, Nebraska on March 31, 1883, making him almost 22 years older than his wife. In his article — "Locals drawn into 1930's most notorious murder" — on thenewsguard.com, Oregon State University communications instructor Finn J. D. John, writes:

They weren't yet married when Dr. Judd left the state hospital in Evansville to take a position in Lafayette, Indiana. Ruth McKinnell quit her hospital job, moved to Lafayette, and became a telephone operator. They were married in Lafayette in 1924. She was 19; he was 41. Max Haines, in his book, "True Crime Stories," says Ruth McKinnell was Dr. Judd's second wife. In 1920, according to Haines, Dr. Judd married 17-year-old Lillian Colwell, who died just a month after their wedding. Haines says the death was from natural causes. Another Associated Press story (February 5, 1932) published in the New York Sun, said Dr. Judd testified during his wife's trial that he'd been a medical practitioner for 22 years; had been in charge of the Morningside Hospital in Portland Oregon; had cared for the insane of the territory of Alaska, and had been on the staff of the State Hospital for Insane at St. Peter, Minnesota, as well as the Indiana State Home for the Insane." His travels continued. After marrying Ruth McKinnell, Dr. Judd took a position as company doctor for a mining firm in Durango, Mexico, but lost that job either because of his morphine dependency or because of a political uprising in that part of Mexico. The Judds then moved to California, where, because of her tuberculosis, Mrs. Judd spent time in Lavina Sanitarium in Pasadena. But the Judds needed money, and the best the doctor could do was a job in El Paso, Texas. He left his wife in California. When she left the sanitarium, she went to El Paso to rejoin her husband. Here again the story is fuzzy. She didn't remain with him, and in one of her 1931 newspaper "confessions" says she headed back to California, but stopped along the way in Phoenix, and decided to stay. This was June, 1930. Meanwhile, Dr. Judd was soon out of work in Texas. It was during her first few weeks in Phoenix that Ruth Judd provided yet another version of her husband's first marriage. The head of a Phoenix employment agency who received the application of Ruth Judd for a position as a domestic servant, told the Associated Press that Ruth Judd said her husband's first wife was After Ruth Judd settled in Phoenix, Dr. Judd worked briefly for a mining company in Bisbee, Arizona, before finding work in California. From the summer of 1931 until his death in 1945, Dr. Judd lived with his sister, Carolina Judd, a California teacher, then moved to a sanitarium, and, finally, a Veterans Administration hospital in Los Angeles. In the spring of 1931, he did manage to live for a short time with his wife in Phoenix in a bungalow duplex next door to the one shared by Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson. While living with his wife, Dr. Judd met Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson, as well as John J. "Happy Jack" Halloran, a partner in a lumber company and a man intimate with all three women involved in "The Trunk Murders." It's not clear whether Dr. Judd knew his wife had cheated on him with Halloran. She resumed her relationship with Halloran when Dr. Judd left Phoenix, though that relationship had been changed by "Happy Jack's" involvement with her neighbors. |

Ruth's brother, Burton, was 20 months her junior. When interviewed by police after the trunks had been opened and his sister was in hiding, he said, while growing up, she had "almost insane fits," particularly when the family moved to Darlington, Indiana, which, I believe, was 1923, when she was 18 years old. "Sis liked a good time," said Burton, who said she rebelled against her father who was very strict. He said his sister never read a whole book. "She couldn't concentrate on one thing long enough to finish a book." In 1933, when his sister's sanity was on trial, Burton McKinnell and his parents would testify they believed Ruth was always insane, though people had to wonder why they kept that to themselves for so long. Burton McKinnell didn't spell it out, but it appears the move to Darlington had been triggered by an incident near Olney, Illinois, where the McKinnells had lived previously. On October 31, 1931, the Hearst-owned Universal Services offered part one of an eight-part series called "Ruth Judd's Own Story." While it would go on to introduce her bogus self-defense explanation of the murders, part one included a revealing story about the Olney incident and a girl she hated. |

|

Rev. M. E. Lawler, pastor at Calhoun, Illinois, remembered the incident differently. He found Ruth McKinnell hiding in his garage, and said she was wearing only a gunny sack sweater. According to an Associated Press story (October 21, 1931), this happened in 1922 and the teenager was taken to her home, where she told a story about being chloroformed and abducted, then driven to a place many miles away. She escaped nude, she claimed, and found the gunny sack later. For two nights she walked railroad tracks in her bare feet, she said, then stopped at the pastor's garage. She accused a Montezuma, Indiana, youth of being one of her abductors, but he was proven innocent. The mother of the youth produced a letter from Miss McKinnell to her son, claiming he was the father of her non-existent baby. A year later, her parents moved to Darlington, Indiana, but she soon struck out on her own, finding a job many miles to the west at the state hospital in Evansville. She met Dr. Judd, and they had their first date in August, 1923. The following April they were married in Lafayette. According to part one of "Her Own Story," a few weeks after their wedding, she and Dr. Judd moved to Mexico, where he was hired as the company doctor for a mining concern. She and the doctor lived on the second floor of the hospital building.

According to Finn J. D. John's article on thenewsguard.com, Ruth Judd suffered two miscarriages in Mexico, which could account for the hysteria. She said it was rebel fighting that caused her and her husband to leave Durango. She also went out of her way in one of her newspaper articles to say this about the mining camp: "We ate at the club, with young mining engineers. There is another thing. You can prove that I have never in any shape or form flirted with any of the men. I do not believe there is a single one of them who would not try to come to my rescue now and do anything in the world for me." Thus she tried to put down a rumor that may have existed only in her head. In any event, none of the young mining engineers made an attempt to rescue her. Mrs. Judd said she became fluent in Spanish while she was in Mexico, and when circumstances forced her and her husband to move to Los Angeles, her language skill landed her an unusual job at a Broadway Department Store. In "Her Own Story," she said,"I worked as an interpreter." The Judds moved around so much that their location at any specific time from 1926 to 1930 is a blur, but in June, 1930, she was on her own in Arizona. In part three of the newspaper series, she said after being in Phoenix only two days, she was hired as a governess by Leigh Ford — she says he was a financier. Mrs. Ford was a hospital patient at the time. Ford's next door neighbor was Jack Halloran. The governess job lasted only two months. In August, she found a position at the county physician's office. She says she didn't know it was a political job, and she lost it as the result of the November election. “On Armistice Day, I applied for a position in the offices of Dr. H. J. McKewan. I got the position the next day, so all in all, I was out of a job only four days." Weeks later, Dr. McKewan moved his offices to the Louis Grunow Memorial Clinic, which is where Ruth Judd met Anne LeRoi in early January, 1931. (Other sources say Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson did not arrive in Phoenix until February, but the biography on findagrave.com has the two women moving the previous fall, perhaps as early as September.) “Now comes the part of my story that to me is the most dramatic, the most vital, the most tragic — even more tragic than the story of what actually took place in the room when I killed the two girls," Ruth Judd wrote in part three. "It is the story of my meeting with Anne Le Roi. It is the story of my meeting with Hedvig Samuelson. It is the story of our friendship and our happiness with those two girls. Now they call them my ‘victims.’ ” I'll get to the murders later, but won't use the version she described in the 1931 newspaper series. When she fled the Los Angeles train depot after failing to retrieve the luggage, and her brother dropped her off downtown, she went to the department store where she had worked a few years before, and hid there overnight. The next morning, she said, she went to a drug store, and with the money given her by her brother, bought some green dye, and returned to the department store, and, using a restroom, changed the color of the dress she was wearing. While Winifred Van Duzer described Ruth Judd's hair as "copper-colored," she said later in her article that the woman's natural hair was a shade of brown. The Los Angeles baggageman told police to look for a redhead, so her hair at the time also was a dye job. She usually was described as a blonde, though, for newspapers at the time, "blonde" was code for "wicked" or "sexy." No doubt, Mrs. Judd was attractive, though noticeably underweight, and she looked best on those few occasions that she smiled. Otherwise, her mouth was Mrs. Judd's worst feature, and she usually looked sullen or scared, which, of course, was understandable. Because she'd go on to spend many years in a Phoenix mental facility, from which it was easy for her to escape, Mrs. Judd kept her name in the news for 40 years. She was usual captured rather quickly, but in 1962 made the last — and most successful — of her seven escapes. She wasn't caught until 1969, having lived seven years in San Francisco as a live-in maid named Marian Lane. Just two years later, Ruth Judd was paroled, and remained free until her death in 1998. Ironically, it was her "clean record" during seven years as a fugitive that helped convince the Arizona parole board she should be released. Her success at grabbing attention and winning sympathy must have inflicted much additional pain on the families of two young women who'd been virtually forgotten — the two women Ruth Judd had murdered. |

The Bobb Edwards biograph says, in 1929, she was a registered nurse who'd moved to Alaska to become the superintendent at the Wrangell General Hospital. Alaska was a territory in those days, not a state. And there were only about 60,000 residents in all of Alaska. Wrangell is an island, and in 1929 was about as desolate a place as a person could find, so it's no surprise that within four months, Anne LeRoi left to take a better job at St. Ann's Hospital in Juneau, where she soon met Sarah Hedvig "Sammy" Samuelson, an elementary school teacher. The two women quickly became close friends, and when Miss Samuelson was diagnosed with tuberculosis, Mrs. LeRoi decided to move with her to a hotter, drier climate. In those days, the prescribed cure for many tuberculosis patients was Arizona. Unfortunately, much of what I found about Mrs. LeRoi was from various "confessions" by Ruth Judd. An exception was something from "True Crime Stories" by Max Haines, who said, in 1925, Miss Imlah was training to become a nurse in Portland, Oregon. Then, in the space of four years, she was twice married and twice divorced. Her first husband, according to Haines, was Walter Monroe, her second was LeRoi James, but I suspect Haines got the name reversed. I never heard of a woman taking as her last name the first name of her ex-husband. (Another source said she married her second husband in Alaska, and he may have been the reason she left Oregon.) In part four of the 1931 Universal Services series that purported to tell Ruth Judd's own story, she described Anne LeRoi as "absolutely the prettiest girl I had ever seen in my entire life!" She added, however, "She didn't take a good picture at all." Mrs. LeRoi may have had a beautiful face, but in 1931 she had a weight problem, and was described by International News Service reporter J. B. Campbell (October 21, 1931) as being "a rather large woman of a slightly mannish type" who weighed 150 pounds. It was her weight that led people to believe Ruth Judd must have had help in putting the body in a trunk, but this is rather easily explained once it is accepted Mrs. LeRoi was asleep on her bed when she was murdered. (Ruth Judd tried to convince police the murders happened during a breakfast argument when she was attacked by both women. Neighbors reported gunshots being fired hours before; that's when the murders actually were committed.) Ruth Judd met Anne LeRoi when she started work as a secretary at the Grunow Clinic in Phoenix, where Mrs. LeRoi was employed as an X-ray technician. While some stories say Miss Samuelson also worked at the clinic, Mrs. Judd says "Sammy," because of her tuberculosis, remained at home in the bungalow she shared with Mrs. LeRoi, and did the housework and cooking. Because of their living arrangement, there was much speculation Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson were lesbian lovers, but Mrs. Judd indicated in both her newspaper articles and her 1933 confession letter that both roommates were involved with "Happy Jack" Halloran, and had other boy friends. They shared a bedroom, but slept apart in twin-sized beds. Mrs. Judd's first remarks about Mrs. LeRoi indicate she became attached to Halloran, and was upset Mrs. Judd was introducing him to other women. One nurse, Lucille Moore, was a particular sore point. During the period Mrs. Judd claimed she had killed the two women in self-defense, she put the blame on an argument that stemmed from Mrs. LeRoi's jealousy. However, in the confession she wrote in 1933 (and didn't become public until 81 years later), Mrs. Judd says Mrs. LeRoi didn't really care about Halloran, but was taking advantage of his generous nature. More on that letter later. Two days after the bodies of Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson were discovered in Los Angeles, some newspapers reported Mrs. LeRoi had a fiancé, Emil E. Hoitola, an Oregon electrical fixture salesman from Portland. That's where her parents lived, and where she had spent some time that summer. Hoitola told reporters the wedding was set for Christmas, though another source said it would take place in June, 1932. If Mrs. LeRoi really were engaged, Mrs. Judd didn't know anything about it. |

When the larger trunk was searched in Los Angeles, police found many letters and papers, including a diploma from the North Dakota State Normal School in Minot, issued to Hedvig Samuelson, July 24, 1925. While not impossible, it's unlikely Ms. Samuelson would have finished college at the age of 17, or have completed two years of teaching in Alaska before tuberculosis prompted her to move to Arizona. An October 21, 1931 International News Service story out of Los Angeles, by J. B. Campbell, described Ms. Samuelson as "extremely feminine and of the clinging vine type." She was estimated to weigh 125 pounds. In her 1931 newspaper series, Ruth Judd said of Miss Samuelson, “She was lovely, too. Sammy takes a very good picture. That is, she always did.” And that's what I noticed, too. There are several photos of Ms. Samuelson online, and most of them show a person you wouldn't expect from someone often described in old newspaper articles as an "invalid former school teacher." She looks more like the life-of-the-party type. Little is known about Ms. Samuelson, so her great-niece, Sunny Worel, set out to write a book about her tragic relative, but died before she finished the project. Ms. Worel's mother, Janet, picked up the work, and in 2015, "Sammy and Sunny: The Story of Hedvig Samuelson, Murdered by Winnie Ruth Judd and The Story of Sunny Worel's Search for Sammy" was published. Not exactly the world's catchiest title. In Ruth Judd's bogus self-defense explanation, she claims Ms. Samuelson threatened her with a .25 caliber pistol that just happened to be lying around. In truth, the gun belonged to Mrs. Judd and she brought it with her when she sneaked into the LeRoi-Samuelson bungalow on the night of the murders. Interestingly, Ruth Judd was never tried for the murder of "Sammy" Samuelson. The state of Arizona had what it needed after Mrs. Judd was convicted of killing Anne LeRoi and sentenced to be executed. When that later was changed to a life sentence, the state was still satisfied, though the Samuelson family probably was unhappy. I think the state wasn't eager to take this case to court because of its grisly aspects. It was "Sammy" Samuelson whose body was dismembered. |

After California native John Joseph Halloran moved to Phoenix, Arizona, he became a partner in a successful lumber business. By the time he met Ruth Judd in 1930 — he was 43 years old, she was 25 — Halloran had a wife and three children, something Mrs. Judd barely acknowledged in her written confessions and newspaper interviews. But, then, Halloran himself barely seemed to acknowledge his family responsibilities. I have a theory why Ruth Judd, who'd eventually admit Halloran was the love of her life, went out of her way to introduce him to other women. Included in the two documents written or dictated by Mrs. Judd, you can find a reason she was driven to the breaking point by one of her rivals. It was the same reason that drove her to accuse of boy a raping her in 1922. To me, a bigger question is why she tolerated Halloran, who'd show up at her place — or at the bungalow duplex shared by Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson — late at night, usually drunk, often with a friend or two. In part five of her Hearst newspaper series, "Her Own Story," she described Halloran as a married man who was "only being kind to us — that is all!" That wasn't true, of course, but it's what she usually said, even to herself. During the 1932 murder trial, Dr. Joseph Catton, a San Francisco alienist (psychiatrist) who'd talked to Ruth Judd, quoted her as saying she loved Halloran "with all my heart and soul, more passionately than I ever loved my husband." She wrote in her 1933 confession that her affair with Halloran began on Christmas Eve, 1930. She and Halloran continued to see each other until Dr. Judd came to Phoenix in the early spring. The chronology is a bit vague at this point, but Mrs. Judd's confession letter says she and her husband lived together for awhile next door to Anne LeRoi and Sammy Samuelson. When Dr. Judd arrived, she wrote, she stopped seeing Jack Halloran, but since he was now visiting Anne LeRoi and Sammy Samuelson several times a week, he was bound to notice their neighbors. "Halloran found out we lived next door. He became a friend of my husband and a frequent visitor at our home." But by summer, Dr. Judd had found work in California, Anne LeRoi became sick and returned briefly to Oregon to see her family, and Ruth moved in with Ms. Samuelson. Halloran was a frequent visitor. It was when Mrs. LeRoi returned from Oregon in August that thoughts of murder occurred to Ruth Judd. As for "Happy Jack," he eventually arrested for being an accomplice in the murders, but there was no proof, no motive, and the charge was dismissed. His lumber company partners eventually forced him to leave the business, but despite all the bad publicity he received about his playboy ways, Halloran's wife apparently stood by her man. Amelia Marie Halloran died in 1963, at the age of 76. "Happy Jack" lived another 13 years, dying in 1976 when he was 89. There's no proof Halloran had any of the political or police clout claimed by those who believe Ruth Judd took the fall for a murder he engineered. I found it interesting that when the murders were discovered, and Halloran was first questioned, he said what may have set off Mrs. Judd was a kiss he gave "Sammy" Samuelson the night before the murders when he gave her a present — a new radio. |

Was it jealousy? Yes, but more This prompted Sammy to write a letter to her sister, Anna Anderson of Chicago, who later shared that letter with the Associated Press. The letter, dated August 10, read:

Part of that is open to interpretation. In her writings — both for the newspaper series in 1931 and her confession letter of 1933 — Ruth Judd often referred to her husband not by name, but as "doctor." But it's possible Ms. Samuelson was referring to a doctor at the Grunow Clinic where Ruth Judd worked. After the murders, police found, in Ruth Judd's apartment, a letter written to her by her husband. It said, in part, "I hope you will let me know as soon as you can what the chances of your clinic closing or your doctor's quitting. I hate to think of you being alone." As for Dr. Judd, he was — or soon would be — a patient at a sanitarium in California. MS. SAMUELSON was correct. Ruth Judd didn't belong in an apartment with Anne LeRoi, and within two months found her own place. After the murders, it was learned the three women had argued over a pet cat. Mrs. Judd wanted the animal put down because of its behavior; Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson refused. (This was the version of the dispute presented in newspapers. Later it would seem odd, because Mrs. Judd would keep cats with her during her short stint in prison, and was allowed to take them with her to the hospital where she would spent most of the next 38 years. She also had a pet cat at the time of the murder. Perhaps her cat and one belonging to the other women did not get along.) But the anger festering inside Mrs. Judd toward Mrs. LeRoi had nothing to do with a cat. Flash back to the 1922 incident involving a girl named Beulah, who began dating Ruth McKinnell's former boy friend. Ruth couldn't stand being twitted afterward. Now substitute the word "taunted" for "twitted." A very interesting aspect of the case — to me, anyway — was that 18 months before Mrs. Judd explained to her lawyer what drove her to murder Mrs. LeRoi, the reason was spelled out concisely by a Phoenix doctor and reported by R. J. Birdwell of Universal Press in an October 22, 1931 article:

Actually, the weapon was the 25-caliber automatic pistol found in Mrs. Judd's hat box at LA train station. Unfortunately, in the only copy of that article I was able to locate, the last line — in which Dr. Mauldin explained how he reached his conclusion — was missing. But he arrived at his theory without talking to Mrs. Judd after the murders, because the doctor was in Phoenix at the time they were discovered, and she was in California. However, he might well have known the woman previously since the medical community was tight, and she had briefly worked in the county physician's office. It's possible, I suppose, that Ruth Judd could have seen Dr. Mauldin's theory, and decided to borrow it. Here is a portion of the 1933 letter Ruth Judd wrote to her attorney, H. G. Richardson: |

|

She considered talking to a priest (It's not explained what she meant by "waiting next door") Soon after she returned to her place, she says, Jack Halloran showed up with a drunken friend she identified as "Mr. Ryan." She said the man propositioned her, and when she resisted, put two dollars down the front of her pajama blouse before Halloran intervened and calmed her down. This part of her confession made me wonder about the true nature of her relationship with Halloran. I believe, in her mind, Ruth Judd wanted to end that relationship, and felt by introducing him to other women, he might stop coming around. But when he actually took an interest in these women, she became angry, but not at him. When it came to "Happy Jack" Halloran, Ruth Judd seems to have a blind spot and infinite patience. At 4 p.m. the next day — Thursday, October 16, 1931 — she said Halloran called and asked her to arrange for a nurse named Lucille Moore to join them, Mr. Ryan and another man — named either Thompson or Townsend — that evening. ADMITTEDLY, I'm trusting this 1933 letter for the most accurate account of the murders Ruth Judd ever offered, even though parts of it seem straight out of a screwball comedy. According to Mrs. Judd, Halloran said he had a radio to give Sammy Samuelson, but instead of dropping it off before coming to dinner, he picked up Ruth Judd, who directed him to Lucille Moore's house. From there, they went to the Sammy's place where she and Anne LeRoi were entertaining Ryan and Thompson (or Townsend). Before Halloran left the car to give Ms. Samuelson the radio, Ruth asked him not to tell Mrs. LeRoi she was out front, but, of course, he told Anne, and when Ruth found out, she became very upset. (Word was, Ruth Judd's tantrums were fierce.) Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson walked the men to the car, and hot words were exchanged between Mrs. LeRoi and Ruth Judd, but when Ruth got back to her place with Ms. Moore and the three men, the conversation took a weird turn. While Ruth Judd was raised by a Methodist minister, she may have felt a guilt we often associate with another religion. In describing her torment over Anne LeRoi's taunts, and, I'm sure, her reluctance to admit her true feelings for Jack Halloran, Mrs. Judd wrote, "I thought although my family was Protestant, I might find relief in becoming a Catholic." That night, she mentioned this to Halloran, who most likely was raised Catholic. He "picked up the bottle of luminal on my dresser and said, 'Are you or have you gone to taking this dope?' I said, 'Yes, I take it to sleep. I don’t know what is the matter with me; sometimes I think I am losing my mind.' " According to her confession letter, she again told Halloran she was considering Catholicism because "if I would become a Catholic, my mind might get a rest. I wish I could talk my whole soul out to some priest for relief." But for Ruth Judd, there was no relief in sight, and that was even worse news for Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson. |

The deed is done "Never did I have the slightest dream of hurting Sammy," wrote Ruth Judd in her confession. "She simply never entered my mind. Except to get Anne, stop those taunts so I could sleep. Nothing more did I think of. I took the gun and a knife. How I would do it I was not sure . . . Jack was as intimate with Sammy as Anne, but it was Anne's cruel taunts that haunted me." She says she arrived at the bungalow about the time Evelyn Nace was leaving. Ms. Nace was a clinic nurse who'd also been invited to play bridge. She'd later tell police she left the bungalow about 9:45 p.m. Mrs. Judd said she hid until Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson retired for the night. At this point, her confession begs further explanation. She says again she hid in the house next door, but also claims to overhear conversation between Anne and Sammy, criticizing Ruth for introducing Jack Halloran to Lucille Moore, because Ms. Moore had syphilis, or so Anne LeRoi claimed, according to Mrs. Judd. WHEN RUTH thought the two women were asleep, she entered the bungalow through an unlocked front door. I don't think it matters much whether Ruth Judd actually sneaked in, or whether she showed up late and the two women invited her to stay over, and she slept on the couch. What was important was Ruth Judd was armed with a .25 caliber pistol and what could have been the surgeon's knife that would be found in the hat box that was delivered to Los Angeles. Police would say the murders were committed shortly after Evelyn Nace left; Mrs. Judd, in the 1933 confession letter, said she killed the women after the milkman arrived, between five and six o'clock. Whatever time it was, Ruth Judd said Anne was in bed, Sammy was in the bathroom. That much has to be true, but when Ruth says, "I crept past the bathroom door, shot Anne. It was a low shot," that is a lie. Anne LeRoi had powder burns on her face. She was asleep when she was shot at close range. Some stories said she was shot three times, but I don't think that's possible unless Ruth went back after she killed Sammy, and put two additional bullets in her primary target. "What fell, Anne?" That's what Ruth says Sammy shouted after the first shot. Here Ruth Judd again tried to build a self-defense case for the second murder. "I was hurrying past the [bathroom] door; Sammy came out demanded to know what was the matter. I was limp, she completely took the gun from my hands." Then, she says, there was a struggle, during which Sammy was killed and she was wounded. IT MAKES more sense to me that Ruth Judd momentarily froze, but fired her first shot when Sammy lunged for the gun. The first shot may be the one that struck her in the shoulder. What is most important is Ruth Judd's bullet wound. That's the "something" that disproves alternate theories of the murders. At some point, Ruth Judd and Sammy Samuelson became tangled with each other, perhaps before the first shot, but I think it was after that shot, when Sammy's momentum carried her forward, but she was too stunned by the first shot to put up a fight. While they were tangled, Ruth Judd fired a second shot; it went through Ms. Samuelson's heart and out her back. Phoenix Sheriff James R. McFadden later offered an explanation for the bullet that was found lodged in Ruth Judd's left hand. "The bullet that passed through the heart of Miss Samuelson was the same slug that was embedded in Ruth Judd's hand," said McFadden. "She shot the girl twice, and probably supported the body with her left hand while firing the final shot with her right. The bullet passed through Miss Samuelson's body and stopped in Mrs. Judd's hand. If that bullet hadn't hit anything before it struck her hand, it would have gone through." (There actually was a third shot — to Ms. Samuelson's head.) Many people speculated Ruth Judd's wound was self-inflicted, but how could she shoot herself in such a way that she caught the bullet with her left hand? Ruth Judd came away that evening with a slug lodged at the base of her middle finger. That slug, when removed by a doctor in Los Angeles, matched others that had been fired from her pistol. (Some have speculated two guns were used, but police discarded that theory.) Some questioned the story of a struggle between Ms. Samuelson and Mrs. Judd on the grounds Sammy was supposed to be a bed-ridden tuberculosis patient. She had tuberculosis, but was not bed-ridden. For that matter, Mrs. Judd also had tuberculosis, and alleges, in true Ruth Judd style, that she was sicker than Sammy, but continued to work. Certainly photographs suggest Mrs. Judd was ailing. If so, how could she dissect Ms. Samuelson's body? That wasn't the only thing that seemed beyond her capability. |

Did she have the skill and strength? On October 21, 1931, two days after Mrs. Judd and the luggage arrived in Los Angeles, the Phoenix crime scene was visited by William J. Burns, former director of the United States Bureau of Investigation. (He would be succeeded by J. Edgar Hoover, and the organization's name would be changed to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.) Burns also had headed his own private detective agency, and was sometimes referred to as America's Sherlock Holmes. In an article for the International News Service, Burns wrote, "It has been said that Mrs. Judd could not commit the crime alone, that she was not strong enough. I have seen persons, under stress of violent emotion, commit the seemingly impossible." He called the murders "a stupid crime committed by a person with a single-track mind who decided what to do on the spur of the moment . . . Putting myself in the murderer's place, the murderer seems to have said: 'I will get rid of these bodies. I will ship them as far away as possible. I will load them in a trunk and send them to Los Angeles, where I can dispose of them at my leisure' . . . Why all this trouble of shipping the bodies when they could so easily have been disposed of in the vast desert lying about this city?" That question trumps the argument Ruth Judd had an accomplice, unless the accomplice were just as short-sighted as she was. "Sure, Ruth, send the bodies to Los Angeles, and you go there, too. That'll give you another twelve hours or so to be caught. If you do make it to Los Angeles, get your brother to help put those two trunks in his car in full view of the baggageman. You may need to ask him to help you. Good luck, and it's been nice knowing you!" THERE ARE those who strongly believe Ruth Judd had help from two men — Jack Halloran and an unnamed doctor, a friend of hers, who responded to her call and did the dirty work for her. (She told police in Los Angeles she couldn't cut up a chicken, must less a human body.) This anonymous doctor was never pursued because he died shortly after the murders, or so it was said. Here's the problem with that theory: If a friendly doctor were available, and willing to dissect a body for a murderer, you'd think he'd stick around long enough to remove the slug from the base of Ruth Judd's middle finger. Ah!, counter the skeptics, but she didn't have any wound until she shot herself a day later. Sorry, but if she shot herself in that spot, she'd have been left with no middle finger. But some people said they didn't see any bandage on her left hand when she went to work on Saturday. Think about that — she left the bodies in the bungalow that morning, and went to work, albeit a little late. These skeptics overlook the statements of Ruth Judd's more observant co-workers who noticed the bandaged left hand that day, even though she tried to keep it out of sight. Mrs. Judd was married to a doctor, and while they were often apart, she lived with him above a hospital in Mexico, and she was there long enough to become fluent in Spanish. I believe she learned a few other things, too. And while she said she used a kitchen knife to dissect Ms. Samuelson's body, I think she had brought something sharper to the bungalow that night. She knew she'd have to dismember at least one body. Another thing about Mrs. Judd's strength. Dr. Judd told police his wife was ill with tuberculosis even before they were married, so she was sick while they lived in Mexico a year later. Granted, you can't trust everything the woman said or wrote, but in Part Two of "Her Own Story," she wrote of their time in Mexico when they had to leave Durango, but all the railroads had been destroyed by revolutionists:

I doubt whether she did any of the carrying, and perhaps she rode a mule, but that trip couldn't have been easy. My point: the woman was stronger than she looked. Another question is whether Sammy's body was dismembered at the bungalow or at Ruth Judd's home. I think it must have been done in the bungalow bathroom because Mrs. Judd wouldn't be able to lift Sammy into the trunk. Anne was heavier, but she was on her bed, and could be rolled into the trunk, which belonged to Sammy, who stored it in the bungalow's garage.

She wrote in her 1933 confession that she called the office and told them she would be late. An hour later, she said, she called Dr. Percy Brown, and, trying disguise her voice, said she was Anne and wouldn't be at work that day. When he asked why, she hung up.

Mrs. Judd said she stayed at the clinic until four o'clock, went to her house, fed her cat, then went back to 2929 North Second Street at six.

I don't believe she used two cheap kitchen knives, not for the whole job, anyway. I believe she knew beforehand she would have to to this to one or both of the bodies. What she doesn't mention is what she did to the faces of both her victims. Police and doctors who viewed the bodies after they arrived in Los Angeles said both faces had been badly beaten, and were nearly unrecognizable. One newspaper story said Ms. Samuelson had been shot three times in the face, but I think that report was an error. (Of special interest to me was Ruth Judd's use of the expression, "irresistible impulse," which years later became the heart of a defense successfully used by lawyer Paul Biegler, played by Jimmy Stewart, in the 1959 movie, "Anatomy of a Murder." Benefiting from the strategy was an Army lieutenant, played by Ben Gazzara, who had murdered a man for raping his wife, played by Lee Remick. The movie was based on a book that was based on a real 1952 murder. "Irresistible impulse" was considered a rare form of an insanity defense, but the circumstances didn't apply in the Ruth Judd case.) |

Help is on the way On Saturday evening, after placing Sammy's body parts in the trunk with Anne's body, Mrs. Judd phoned Lightning Delivery Service, and three men were sent to the bungalow. This was about ten o'clock. Driver Richard M. Swartz went to the door, and a woman — whom he later identified as Mrs. Judd — greeted him and said she had a trunk to be taken to the railroad station. Swartz told police it was dark inside the apartment, and Mrs. Judd refused to turn on the lights. Swartz made his way to the trunk, asked why it was so heavy, and she simply replied, "Books." I suspect he didn't believe her, but he was working in the dark, and if there were blood on the floor, or leaking from the trunk, he couldn't see it. Swartz summoned the other two men from the truck, and they helped him drag the trunk outside and place it aboard. Swartz informed Mrs. Judd he could not take it to the railroad station unless she accompanied him, because he knew there would be an excess charge to ship the overweight trunk to Los Angeles. She told him to take the trunk instead to her home at 1130 Brill Street. She called a taxi and met the men there. She said the men left the trunk in her bedroom, and she returned to the bungalow, apparently aboard a streetcar. She said she "turned the hose on the porch, went in the house, got the blood-soaked mattress and carried it over to a vacant lot at the corner of 3rd and Pinchot where I struck perhaps five matches to it, but saw my car coming, the one I had ridden out on and ran to catch it. It was the last car on Saturday night." Back at her place, she went to bed and slept late Sunday morning. After she awoke, "I opened the trunk, washed out some towels on top. I could not wring them dry with one hand. I transferred portions of Sammy’s body to the smaller trunk and suitcase." Her landlord, H. U. Grimm, would tell police that on Sunday, he, along with his son, transported what he called "two lead-like trunks" to the Phoenix railroad station. "She said they were books — that's what made 'em so heavy." He said she also had a doctor's bag, though he may have confused this with the hat box. It was Grimm's son, Kenneth, who would knock the pins from under Ruth Judd's self-defense theory during the trial four months later. She claimed she had spent the night with Mrs. LeRoi and Ms. Samuelson, then got into an argument with Mrs. LeRoi over breakfast, an argument that became so heated, Mrs. Samuelson fetched a pistol and threatened Mrs. Judd with it. There had been only one gun in the bungalow, and that was during the few weeks Mrs. Judd lived there, because it was her gun. She claimed she'd left the gun there when she moved out in September, but Kenneth Grimm testified that after Mrs. Judd arrived at the Brill Street apartment, she remembered she'd forgotten to bring her gun with her. Grimm said he drove her back to the North Second Street address so she could retrieve it. Kenneth Grimm may have given Ruth Judd rides at other times during her short stay on Brill Street. When the murders were revealed, and police and the press were grasping for clues, someone in Phoenix recalled seeing Ruth Judd that fall as a passenger in a car driven by a young man. I found a newspaper story from October 22, 1931, that bore the headline 'YOUNG SUITOR LINKED WITH FUGITIVE." He was no suitor; he was her landlord's son. SO DOES Jack Halloran fit into the murder somewhere? Maybe not, but it's possible Mrs. Judd contacted him on Sunday after she finished packing. She needed money to get to Los Angeles. One of Halloran's acquaintances would say later "Happy Jack" had told him he'd been at a house where there were two dead women. The man later retracted the remark, and Halloran would swear he never made the statement, but I suspect Halloran visited Ruth Judd on Sunday at least long enough to give her money for a train ticket and the cost of the overweight luggage, and that she told him what she had done as an explanation for why she was abruptly leaving Phoenix. I believe Halloran chose not to get involved any further. Had he been an accomplice, or, as some suspect, the actual killer, the bodies never would have wound up in two trunks aboard a Los Angeles-bound train. Two people, Lucille Moore, the nurse who had been with Jack Halloran and Ruth Judd on Thursday night, and Dr. R. D. Gaskins, who lived near Mrs. Judd's Brill Street bungalow, told police they received threatening calls from a man who warned them not to talk about the case. That could have been Halloran, attempting to keep his name out of the story, but there was no chance of that. Too many people knew about his visits with the three women involved in this tragedy. Dr. Gaskins helped fuel a theory the murders were linked to drug use. He told police he believed the women involved in the murders used drugs. Lloyd Andrews, the Maricopa County attorney, said Mrs. Judd and Mrs. LeRoi both were addicted the luminal (not to be confused with luminol, a fairly recent chemical made famous in forensics-related television programs because it is used by expose blood that may have been wiped away at crime scenes). Luminal, also known as phenobarbital, phenobarbitone or phenobarb, is a medication of the barbiturate type. It is used to treat anxiety or sleep problems. (Both Dr. Judd and Jack Halloran expressed concern to Ruth Judd about her dependence on luminal.) |

She wanted to be a mother

During her relatively short time in prison in Florence, Arizona, when she was allowed to keep cats, she called them "my babies." Shortly after she was transferred to a mental hospital in Phoenix, she was forced to give up the cats, which she turned over to her brother, Burton. |

Ruth Judd on trial Her self-defense story was torn to shreds, and it was clear to the jury Mrs. LeRoi was murdered, not in the kitchen, but in bed while she slept. When Mrs. Judd was found guilty and sentenced to hang, the state decided it didn't need to punish her with a second trial. The mistake was probably the death sentence. Had she been sentenced to life imprisonment, there might not have been any fuss about Ruth Judd afterward. The biggest reason her defense team — there was a long parade of lawyers involved in her case over the years — set out to prove her insane was to spare her life. And after a few postponements of her execution, an Arizona grand jury recommended that her sentence be commuted, but the state resisted, until she faced a different jury in April, 1933, one that would decide whether she was insane. For them, she put on a terrific performance. The jury got their first taste after they were seated and Mrs. Judd screamed at them, "You're all gangsters!" For whatever reason, "gangster" became one of her favorite insults during the trial. Things got worse as the trial continued. |

|

|

At that point she was ordered removed from the courtroom. Warden Walker carried her away while she swung her arms wildly. Along the way, she shouted, "You're all crazier than I am!" Dr. Judd, who played up his occasional work in mental hospitals, said during his testimony, "If Ruth isn't insane, they had better empty the asylums, for her condition is as abnormal as that of any patient." Dr. Paul Bowers, a Los Angeles psychiatrist, disagreed. While conceding she is suffering from “a state of great fear, and is thoroughly frightened,” he said nothing in the woman's actions had caused him to change his opinion. He added, she has “great histrionic ability.” Dr. Joseph Catton, a San Francisco psychiatrist, also testified Mrs. Judd was not insane. Both psychiatrists felt she was faking mental illness. Dr. Catton discounted the family history that her parents had recited. MRS. JUDD knew the people she had to convince were sitting in the jury box. In a desperate move three months earlier, she changed her story about Jack Halloran, claiming he had helped her dispose of the two bodies, and though he was arrested, he could prove he wasn't with Mrs. Judd when she claimed he was. For that matter, even Mrs. Judd wasn't where she said she was in her umpteenth version of the crimes. Charges against Halloran were dismissed. So she continued to act up during her sanity hearing; she interrupted the proceedings on April 19, screaming for Halloran to be brought in. This was two weeks after her 19-page letter to her lawyer, which began, "I am writing the absolute truth of this case ... This is my first and only confession of the case of the homicide of Agnes Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson." In that letter, she said Jack Halloran had nothing to do with the murders or disposing of the bodies. In any event, she was rewarded April 23 when nine of the 12 men on the jury found her insane. That was the number she needed. Before the jury went into deliberations, they heard a two-hour plea from O. V. Wilson, one of Mrs. Judd’ lawyers, who went a bit overboard: Seventy-five years! I wonder what 1858 case he thought rivaled this one. I also wonder if family and friends of Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson believed justice was served by the jury verdict. As for Ruth Judd, she was taken to an asylum in Phoenix that housed about 250 people, and within a few years Mrs. Judd would begin a series of escapes. I've always had ambivalent feelings about the death penalty, but, yes, I'm glad Mrs. Judd found a way to beat it, but if anyone deserved to be executed, it was Ruth Judd. |

Eventually, Ruth Judd cried, 'Wolf'!' too often One Phoenix police detective is quoted in at least one story about "The Trunk Murders" as being suspicious about where the murders were committed because there was little blood in the bedroom. Well, since only one murder occurred in the bedroom, and the victim was shot in the head at close range while asleep on her bed, you wouldn't expect much blood, since the killer later removed the mattress and part of the rug from the room. And since no luminol was available in 1931, police couldn't tell where there might be blood because Ruth Judd cleaned the bungalow before she left it. One other thing: Since these murders took place long before the era of forensics importance began, the scene was badly contaminated by curious people who were allowed to roam at will. In addition to the missing mattress — later found in the vacant lot where Mrs. Judd had left it — a section of rug on the bedroom floor was cut away, presumably because of blood stains. What is curious, is that most stories say Ms. Samuelson's mattress also was missing That is mysterious for several reasons. Mrs. Judd never mentioned removing it. She'd already destroyed her self-defense argument that claimed the deaths occurred outside the bedroom, why would she remove two mattresses? Several questions about this case can never be answered, but, to me, the most important one was — Who wanted Anne LeRoi dead? Only Ruth Judd had a reason, or thought she had. And I expect she felt the same way about Hedvig Samuelson, though she didn't admit it, not even to herself. But, then, it took her awhile to admit to herself how she really felt about Jack Halloran. |

Odds and ends Years later, Ruth Judd claimed Jack Halloran had arranged for her to meet a man named Williams in Los Angeles, and he would help her dispose of the bodies. Taking the bodies to Los Angeles never made sense, and she couldn't explain why she didn't wait around the Los Angeles station for the man, but instead went immediately in search of her brother. Yet every time she told one of her tales, someone believed her, proving you can fool some of the people all of the time. • I've made no attempt to find out how many female criminals have been nicknamed "Tiger Woman," but came across the names of three of them, including Mrs. Judd. All were guilty of an especially horrible murder, and all displayed ability as an escape artist once captured. Clara Phillips, the earliest "Tiger Woman," escaped a California facility in a matter of months, and made it to Honduras before she was found. She then decided to become a model prisoner, which paid off, because her "life sentence" was finished in less than 13 years. Then there was Eleanor Jarman, "The Blonde Tigress," aka "Blonde Tiger Girl," who escaped prison and disappeared for good. • After Ruth Judd's murders became known, police and press talked to anyone who had something to say about the woman. One of my favorite comments was something said by a Phoenix druggist, who wasn't being funny, because the country was still going through Prohibition, but today it seems humorous to think this man knew Ruth Judd was throwing a lot of "really wild parties" because she stopped at his store and had bought a considerable amount of ginger ale. • Neighbors of Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson had mixed reactions to their lifestyles. About half of those interviewed said the pair were nice young women and very quiet; the other half said they were noisy and wild. Everyone agreed they seldom went out, but, then, after they met Jack Halloran, they didn't have to. • Wallace S. Rawles of International News Service reported on October 22, 1931, that Mrs. Judd was seen on the Sunday afternoon before she left Phoenix in the company of "a youthful admirer" in what witnesses believed was the victim's car, with the "admirer" behind the wheel. If these spottings were true, the young man was probably Kenneth Grimm, her landlord's son. According to Rawles, Mrs. Judd was stopping at the homes of people she knew, claiming she needed money to support her five-month-old child who was in Los Angeles. A lie like that would only work on people who didn't know her well. • The 1933 confession letter often cited in my story wasn't the most famous one people associate with Ruth Judd. While hiding in the Los Angeles department store, she grabbed some stationary, and with a pencil wrote a letter to her husband, then changed her mind and tossed it in the toilet, where the pages were retrieved by a plumber, who turned them over to police. This letter was used against her in her murder trial, though, by then, she had confessed to the crime, and her lawyers used a combination self-defense and insanity strategy. • Apparently Mrs. Judd took her suitcase with her when she boarded the train, then, after being rebuffed in her attempt to get her two trunks, she left the suitcase in the ladies room at the terminal. United Press reported on October 20, 1931, that the suitcase was not found until six hours after the trunks had been opened. The suitcase was found about midnight by a maid in attendance at the rest room. Inside was a body part and the gun Mrs. Judd used to kill the two women. • Ruth Judd's brother, Burton McKinnell, told police his sister phoned him that morning while he was at class. She asked him to meet her and told him she had two trunks at the railroad station. “She said she wanted me to drive down and get the trunks and take them to the ocean and dump them in deep water." He met Mrs. Judd and they drove to the station. He became suspicious, he said, when he noticed insects swarming about the trunks. • As a fan of true crime documentaries, I've watched more than my share, and while watching "Dateline" on the Peacock streaming service came upon back-to-back episodes of 21st Century murders that may have been motivated similarly to the killings of Anne LeRoi and "Sammy" Samuelson. The programs are titled "Vanished" and "Under the Desert Sky," and under the Peacock system are listed as episodes 16 and 14 from season 21 (which doesn't square with the "Dateline" episodes page on imdb.com. Whatever, the victims in both episdes, Michelle Hoang Thi Le of Hayward, California, and Micaela Costanzo of Wendover, Nevada, were murdered by acquaintances who were jealous and envious. In both cases there was no proof the jealousy was warranted because neither victim was involved with the young man the killer wanted. (In the Costanzo case, the young man in question participted in the murder.) I believe Ruth Judd was jealous of Anne LeRoi and furious at the attention she received from both Halloran and her housemate, Ms. Samuelson, and I think Mrs. Judd was jealous of the attention Halloran was giving Ms. Samuelson, and envious because, despite her illness, "Sammy" was more vivacious and likable than Ruth Judd, who was an emotional wreck and believed her life would be better if her two "friends" were no longer in it. |

| HOME | CONTACT |

woman was illegally transporting deer meat, not an uncommon crime in those days. He didn't want to consider a more grisly alternative.

woman was illegally transporting deer meat, not an uncommon crime in those days. He didn't want to consider a more grisly alternative.  Dr. William C. Judd

Dr. William C. Judd killed when thrown from a horse near Phoenix after she and the doctor had been married only a short time. Ruth Judd further confused the issue by saying this happened in 1916, not 1920.

killed when thrown from a horse near Phoenix after she and the doctor had been married only a short time. Ruth Judd further confused the issue by saying this happened in 1916, not 1920.

Agnes Anne Imlah LeRoi

Agnes Anne Imlah LeRoi Sarah Hedvig "Sammy" Samuelson

Sarah Hedvig "Sammy" Samuelson John J. "Happy Jack" Halloran

John J. "Happy Jack" Halloran